The Trauma Tsunami

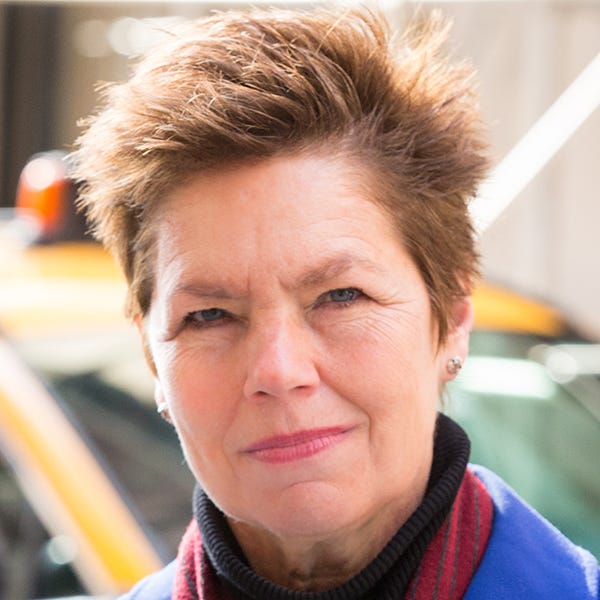

Retired Brigadier General Loree Sutton on today’s mental health crisis and a promising new way to treat PTSD

Loree Sutton is a psychiatrist, clinician and retired Brigadier General in the U.S. Army, where two decades ago she had responsibility for all programs related to mental health and traumatic brain injury. This brought her up-close to the epidemic of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that has afflicted tens of thousands of military personnel and veterans during and after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as millions of others who have experienced trauma. From 2014 to 2019, she was New York City’s Commissioner of Veterans Services under Bill de Blasio before resigning to undertake an unsuccessful campaign for mayor. I met Loree through our mutual friend Garry Trudeau and we sat down to talk about the mental health crisis afflicting this country and a breakthrough therapy to help those with PTSD.

JONATHAN ALTER:

How big of a problem do you think mental health is in the United States right now compared to 20 years ago?

LOREE SUTTON:

We have a huge challenge on our hands. In the military, suicides reached epidemic levels in 2009 that then migrated to the veterans community. And, within our society as a whole, there's been a 30 percent increase in suicides since 2000. This doesn't even factor in where we are today, in the aftermath of the pandemic. We may be done with the pandemic, but the pandemic is not done with us.

What you're seeing now — given the factors of fear, social isolation, loss, grief and illness — is that our lives, our families, and our loved ones, even our workplaces, have been transformed in the process. I don't think we have a historic analog to turn to. We've had prior pandemics, we've had yearslong wars, we've had pieces of what we're experiencing now, but I would call what we are now in a trauma tsunami. And it is one for which our current mental health care system is ill equipped. There are some real glimmers of hope and that's where I'm putting my time and effort right now.

JON:

When you say “epidemic levels in 2009,” what does that mean? What is the incidence [of suicide] in the military?

LOREE SUTTON:

I came into the army in 1981, and, for the first 25 years of my career, the suicide rate in the military hovered between eight and ten suicides per 100,000. As we are quick to affirm, even one suicide is too many — but the range stayed pretty stable and it was well beneath what you saw in civilian society, where the suicide rate typically was in the in the teens per 100,000. What happened in 2004, and over those next four or five years, was a steady increase in suicides, so that by 2009 we had to formally recognize it as an epidemic because we were up to 25, 30 and even beyond per 100,000 — over double what we had seen over the previous 25 years.

“We may be done with the pandemic, but the pandemic is not done with us.”

What happened in 2004, as we got deeper and deeper into Afghanistan and Iraq, is that our political leadership and our military leadership were not viewing this set of wars as a long-term commitment. Do you remember the language used? “This will be a cakewalk” and “we’ll be greeted by Iraqi citizens with flowers and parades.” And of course, it turned out to be anything but that.

Let me give you an example. We didn't have a decade long war in Iraq. We had a series of 12-to-15-month deployments, completely separate battle teams, separate sets of leaders. General Petraeus was one of the few who early on said, “Tell me, how does this end?” Imagine what it’s like for a chaplain to come on board just as the unit is heading for the tarmac to be deployed for a year? What the military calls “dwell time” is the amount of time that a unit would be dwelling at home between deployments. But about one third of the unit who have just deployed from 12 to 15 months have now been sent to another unit which, quite likely, would be gearing up for another deployment. The standard dwell time does not apply to that soldier or his/her family.

JON:

What was the suicide rate during the Vietnam War and for Vietnam veterans? Was it up in the 30s per 100,000? Or was it lower?

LOREE SUTTON:

There were a lot of studies on the Vietnam generation after they returned home, but we don't have sound comparative suicide data or data for their deployment time. Certainly, the Vietnam veterans have had a much worse experience for a whole lot of reasons. One is the social environment, and the lack of support or understanding for the mission. They won militarily, but we lost politically — and the ostracism that Vietnam veterans faced from veterans from other wars was terrible. Folks who won World War Two looked down on the Vietnam veterans for having been the first veterans in our country's history to have lost a war. Let's put it this way. There have been more suicides of Vietnam veterans than those who died in Vietnam. If you look at Iraq and Afghanistan, that's true of those wars, too.

JON:

So there were about 58,000 who died in Vietnam, and more than 60,000 suicides of Vietnam–era veterans. That’s depressing and appalling.

LOREE SUTTON:

We owe so much to the Vietnam Veterans of America insisting on the support that they deserve and have earned. [The late] Max Cleland — he was a triple amputee and member of Congress — was the first Vietnam veteran and youngest Secretary of the VA [Under Jimmy Carter}. It was through him that we got the Vet Centers, which are a huge step forward in providing the supportive environment that vets need.

JON:

My late father flew 31 missions in a B-24. He was shot down by the Nazis; fortunately, they landed over Soviet-held territory. He picked a lot of flak out of his flak jacket and watched as his friends’ planes were blown out of the sky. Going to bed on base after a dangerous mission, he looked at the empty cots around him.

I talked with him about how each war has its different expression for what happens to soldiers afterwards. After World War One, it was called “shell shock”. After World War Two, it was “battle fatigue”. Today, it's post-traumatic stress disorder. But it's basically the same thing. I think what's hard for people to understand is why the incidence would be going up for people who were military support personnel but not combat veterans.

My father didn't suffer from it. He had his own coping mechanisms, which mostly consisted of denial, which brings its own issues. He told me of crew mates who suffered battle fatigue but wondered why this was becoming so common among people who are not combat veterans. What's the answer to that question?

LOREE SUTTON:

Going back to the post-9/11 veterans for a moment: I think there were roughly 7,000 deaths from those two conflicts, and over 30,000 suicides. That's [an increase] by a factor of four in not even 20 years. I hate to say “it depends,” but it does depend. In World War Two, there were close to a half million psych evacuations from the World War Two theater. It was not an easy war at all. [The military] realized early on that for the average infantry rifleman who was stationed at the front lines for a sustained period of time — i.e., for 150 days without being rotated back — 98 percent of those infantrymen “decompensated”[Suffered mentally]. That's what led to the battle fatigue numbers.

Because our standards had been so stringent for bringing in recruits for World War Two, we realized that if we didn't do something we would lose more than we were bringing in. So we set up battlefield psychiatry — the military psychiatry paradigm. They found that for close to 80 percent of folks who had difficulties functioning in their unit, or who had an extreme reaction of decompensation, if they were given basic social support—and hydration, food and rest — they could stay in their unit. That became the basis for what continues to be the military doctrine to this day.

What has changed with this more recent set of wars is the level of exposure. As I was preparing to direct the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury, I talked to a number of Vietnam veteran adjustment counselors, many of whom were Vietnam veterans themselves. They'd been active in the movement to get PTSD established as a diagnosis in 1980. What they told me was: “Ma'am, we thought we'd seen it all. But what these young men and women are coming back with from Iraq and Afghanistan is the worst case of whatever it is that we've ever seen.” That really got my attention. It helped me realize the imperative to embrace building resilience and focus on reintegration into communities across the country.

“What they told me was: ‘Ma'am, we thought we'd seen it all. But what these young men and women are coming back with from Iraq and Afghanistan is the worst case of whatever it is that we've ever seen.’”

We had to ask ourselves “Why is it that this generation is coming back with the worst case of whatever it is we’ve ever seen?” We could either say, as some did, in the early aughts, “Well, this generation obviously just doesn't have what it takes.” And we rejected that. We looked at the research we had, which showed very convincingly that the most powerful predictor of short- and long-term outcomes for troops who were deployed and coming back was the number of days deployed.

Let’s compare the days of deployment and exposure, starting from World War One all the way forward. World War One was about 100 days of exposure per [soldier]. World War Two was 100–200 days of exposure. Then there’s Vietnam. Troops were one-year recruits and so they had about 365 days of exposure, and it was even worse when they got home and got spat upon and rejected by society. When we looked at this generation, even as early as 2008, they had been deployed 300- 500-1000 or more days. By that reckoning alone, it’s no wonder these folks are coming back with “the worst case of whatever it is that we've ever seen.”

JON:

A lot of these guys would do one deployment, and then for personal financial reasons, among others, they would re-up. In retrospect, a lot of them shouldn't have. So now let's fast-forward. After 2013, when Obama was beginning to wind down the wars, did most of these folks get reintegrated? How many of them have continuing PTSD 10 years later?

LOREE SUTTON:

We don't know for sure. There's no single trusted source where veterans will go for their healthcare. (About a third to a half will go to the VA). And it's not only suicide. There was a study that came out earlier this year where they looked over the records of not just confirmed suicides, but overdose and accidental deaths. Factoring those in, the mortality rate rises alarmingly high. It's a raging storm.

I was there in 2007 when we put together the first set of clinical practice guidelines. Researchers in the last two to three years have come to the conclusion that the existing treatment modalities—prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy, and EMDR—are all missing the mark.

JON:

Could you tell us about those existing treatments for PTSD?

LOREE SUTTON:

Under prolonged exposure, as its name suggests, you expose an individual [in therapy] for a prolonged period of time to the worst, most intense sensory aspects of their traumatic experience.

JON:

What is a long period of time?

LOREE SUTTON:

They have to relive it over many hours in the therapy session—the sights, the sounds, the smells. And then they have homework over a 12-week period where they relive it in “in vivo” experiences between sessions. The idea is that somehow by intensely reliving it, you're going to be able to get it out of your system and won't have to relive it anymore. The VA has invested heavily in prolonged exposure, but it just doesn’t work very well for many patients. And, as you can imagine, there are high drop-out rates. And I think there's also a real issue here ethically. When I was in uniform, by 2010, I could not sell what the Army had bought, which was prolonged exposure therapy and a cognitive “top-down” program called Comprehensive Soldier Fitness.

The other two [treatments] do not raise the same ethical issues, but they also don’t work well. Cognitive processing therapy has an [inherent] sequencing problem. With overwhelming trauma, the first part of your mind-body system that goes offline is your cortex—your thinking brain. So why would you imagine that a cognitive intervention would be the most effective frontline intervention in getting you back?

JON:

So, you can't think your way out of PTSD?

LOREE SUTTON:

You can't talk, think, or medicate your way out.

JON:

What's the third option?

LOREE SUTTON:

EMDR — eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. This modality has been around for a while. It came into wide use after the Oklahoma City Bombing in the mid-90s. By following the therapist's hand in a tapping motion or moving your eyes back and forth when reliving the trauma, you rebalance your mind-body system. EMDR has helped a lot of folks. What has happened over the years is they've unfortunately let it become decentralized. There's practically an EMDR Institute on every street corner. And a recent, rigorous scientific review has raised the alarm on EMDR. The review concludes that treatment can no longer be reliably researched because no one can agree on what represents true EMDR. So that's a tragedy.

JON:

You believe we're starting to see evidence of a very promising fourth way, which is being rejected right now by the Veterans Administration. You and Garry Trudeau, who's been working in this area at Walter Reed for a while and wrote an interesting article about it in The Washington Post, think there's this other method called RTM. Tell me what Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM) is.

LOREE SUTTON:

The Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM) protocol builds upon a body of neuroscience research that began in the late ‘60s. It didn't come from clinical psychology or psychiatric literature; it came from neuroscientists who published an article in the late ‘60s that was ignored for 30 years. In the late ‘90s, this got picked up clinically — and was used in conjunction with beta-blockers like propranolol — and then more recently with no medications at all.

It turns out that when you gently reactivate a traumatic memory in humans, you have about a one-to-six-hour window within which you can, through a variety of guided imagery and exercises, restructure that memory. Further, a night of sleep builds the reconsolidation process. The research shows that for most folks, after two to three sessions, the charge of the traumatic memory — its connection to the cascade of mind-body reactions, the flashbacks, the nightmares, the hyper-vigilance, everything that makes PTSD so debilitating — is uncoupled from the restructured memory. The protocol is complete when an individual can talk about what has happened without the reactivity and intrusive reminders that makes it seem as if he or she is reliving it. The research to date demonstrates RTM as being 2-3 times more effective than treatment as usual—that is, prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy.

JON:

You have the patient take a step back, so they are detached from the traumatic experience and they view it almost as a movie in their head that they're watching. Is that the basic idea?

LOREE SUTTON:

Yes. RTM begins with a brief, quickly terminated recall of the traumatic event that is believed to ‘open’ the reconsolidation window; rigorous monitoring throughout the process prevents retraumatization and yields low drop-out rates, averaging less than 10 percent. Through a series of guided dissociative visual imagery exercises, the client engages in the perceptual manipulation of the traumatic memory (e.g., recalling the event from a third-person perspective, viewing it in black and white, in reverse order, and at high speed) in a manner that ultimately allows for recall of the event without triggering emotional hyperarousal. Typically, this protocol is completed within three to five 90-minute sessions administered over a 5-10-day window.

JON:

My understanding is that the training for therapists is much shorter than with other therapies and the duration of the treatment is shorter, which makes it less expensive.

LOREE SUTTON:

Yes. This has major implications in terms of our capacity to deal with this trauma tsunami. There are huge economies of scale to be gained by RTM’s ease of training and its specificity of manualized steps. And, the very specific steps in the model insure that everyone receiving RTM is receiving RTM and not an altered version as has happened with EMDR.

JON:

Why has the VA been so resistant to adopting this treatment?

LOREE SUTTON:

I can't speak for them. I can tell you what they have said publicly. From the outside looking in, it would appear that the VA National Center for PTSD has benefited greatly in financial terms from this juggernaut [of military psychiatry] and they do not want to let go of that. They've invested more than a billion dollars in studying prolonged exposure and these other therapies.

Here's the other thing. When you hear about something like RTM, and you hear: no medications, no drugs, no re-traumatization, four or five hours on average over two to three sessions — and you see the outsized 80-to-90 percent remission rate — it seems too good to be true. But “too good to be true” is hardly a scientific premise–a reason not to do the research. The VA has had a huge amount of research money over the last 15 years. It’s maddening actually, when the agency that has the research money uses it to block promising therapies like RTM. They say, “Oh, no, we don't have enough research on this,” but at the same time, they don't invest in researching it. To date, the VA has never tested or tackled RTM on its merits.

When you hear about something like RTM, and you hear: no medications, no drugs, no re-traumatization, four or five hours on average over two to three sessions — and you see the outsized 80-to-90 percent remission rate — it seems too good to be true. But “too good to be true” is hardly a scientific premise–a reason not to do the research.

The Director of the VA’s National Center for PTSD, has stated—most recently at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies annual conference in 2022—that the VA believes that it has the approaches they want, and they're not extending beyond them. They'll just work to make them better. I find that shocking and unconscionable.

JON:

When I had cancer, I learned that doctors and medical researchers — for all the good they do — are subject to human nature like anyone else. When they and their hospitals are invested heavily in certain treatments, they often aren’t open to ideas from the outside, even if they work better. These folks need to broaden their vision. Are you hopeful that that's going to happen soon? What do you think the time horizon is for more rapid adoption of RTM?

LOREE SUTTON:

If it were up to the National Center for PTSD, it probably would never happen. But when you look at large-scale movements within the VA over the last several years, I find reason for optimism. And it comes not from within the system, but from veterans who raise holy hell. I’ve recently been appointed to serve on a federal advisory committee and we report directly to the [Veterans Affairs] secretary. So, I'm confident that I'll get a chance to talk with Secretary McDonough about breakthrough therapies, including RTM and psychedelics, as well as the politics of PTSD.

JON:

How about working it from Capitol Hill?

LOREE SUTTON:

Given the state of Capitol Hill right now, I wouldn't hold my breath, although this is rolling into an election year. Maybe in this next session.

JON:

Last question: When you became a general, there were only 16 women in the armed forces who were flag-rank officers. Today there are over 100. What difference do you think that makes? If there had been as many when you started as there are today, would some of the things that you pushed for have had a greater likelihood of success?

LOREE SUTTON:

I had so many fantastic mentors in my career — male as well as a few female mentors — that I don't think it's necessarily gender-dependent. I will say that with so many more women leaders at all levels, and the diversity of backgrounds, it's a stronger military. But the military is a conservative organization. During my time at DCoE [Defense Centers of Excellence], I experienced that threat response to innovation from some military leaders and a few political leaders as well. It was pretty brutal. That said, the military has enormous challenges now, in part because of the ongoing suicide epidemics and sexual assaults that have been broadly publicized, as well as the “forever wars” that have not exactly been conducive to parents, teachers and coaches—our largest recruiters—convincing young men and women to consider joining the military. They're having a whale of a recruitment problem right now. Still, there are so many things I wouldn’t change about my time in the military. For the times in which I served, I am confident that I did everything that I possibly could and contributed everything that I knew to contribute.

JON:

Thanks, General Sutton, though now I feel comfortable calling you Loree.

Jon,

Terrific interview. We owe our veterans more. Thank you for bringing these issues forward. We must do better.

Terry

I was struck by Sutton's assertion, toward the beginning of the interview, that "Within our society as a whole, there's been a 30 percent increase in suicides since 2000."

This rather hefty increase in suicides coincides with an ever-increasging surge in the consumption and use of mental health services. In other words, as more people take psychotropic medications and endure psychotherapy, more people are dying because of their emotional maladies.

To do something which does not work, and then to do it again, is the very essense of psychopathological behavior. Ergo, one could argue that the therapeutic community is somewhat disturbed.

I don't think that psychiatry is necessarily a futile and failed field of endeavor. However, I think psychiatrists and psychologjsts need to re-evaluate their treatment strategems.

I wonder: There has been a huge increase in psychiatric problems, and transgenderism, among adolesecent girls, and this has ensued even though there has been an enormous stress on female empowerment, feminism, and the advancement of women over the past few decades. Is it possible that the very things meant to buttress and buoy female self-esteem and health are actualy exacerbating emotional problems in girls ???