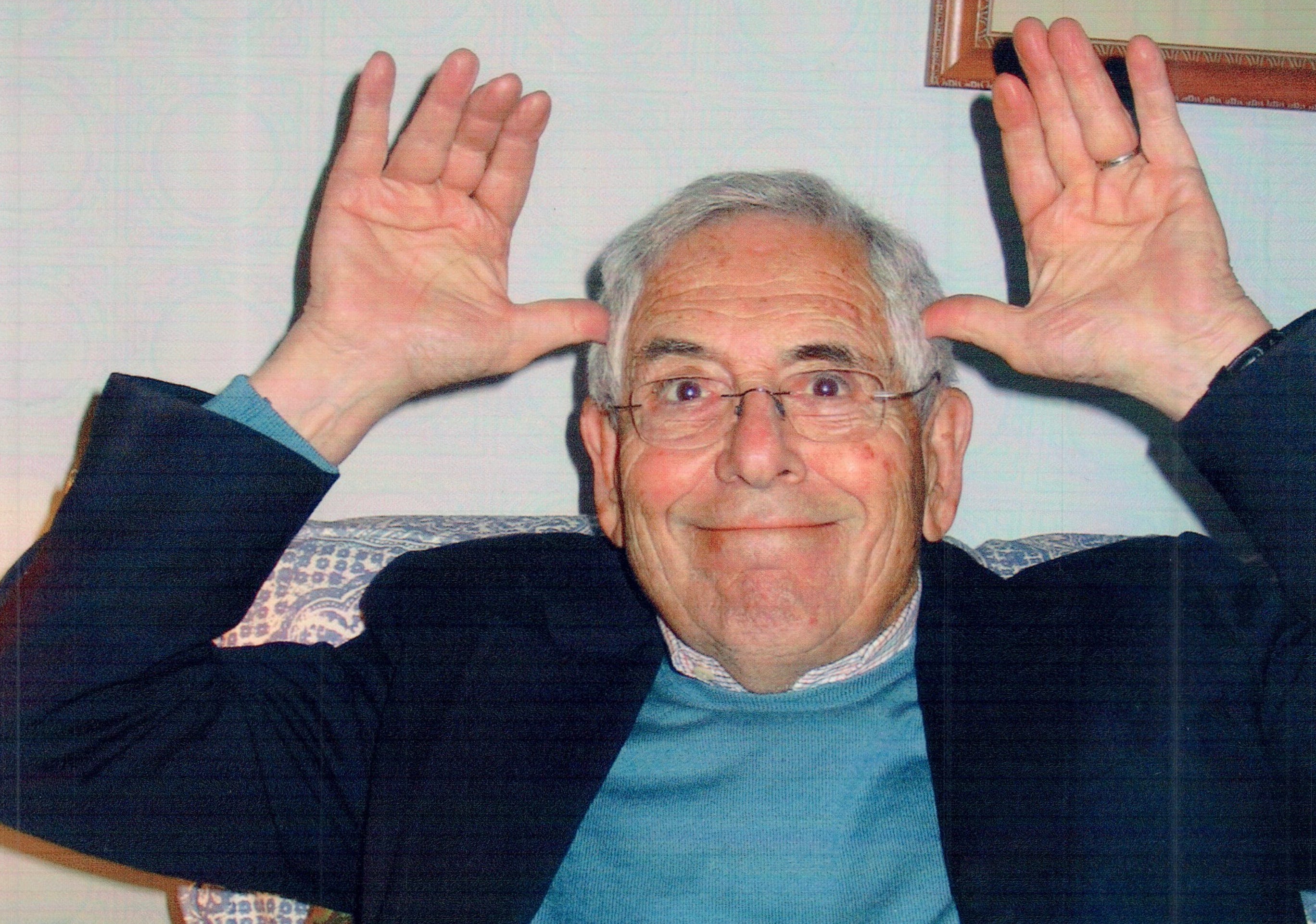

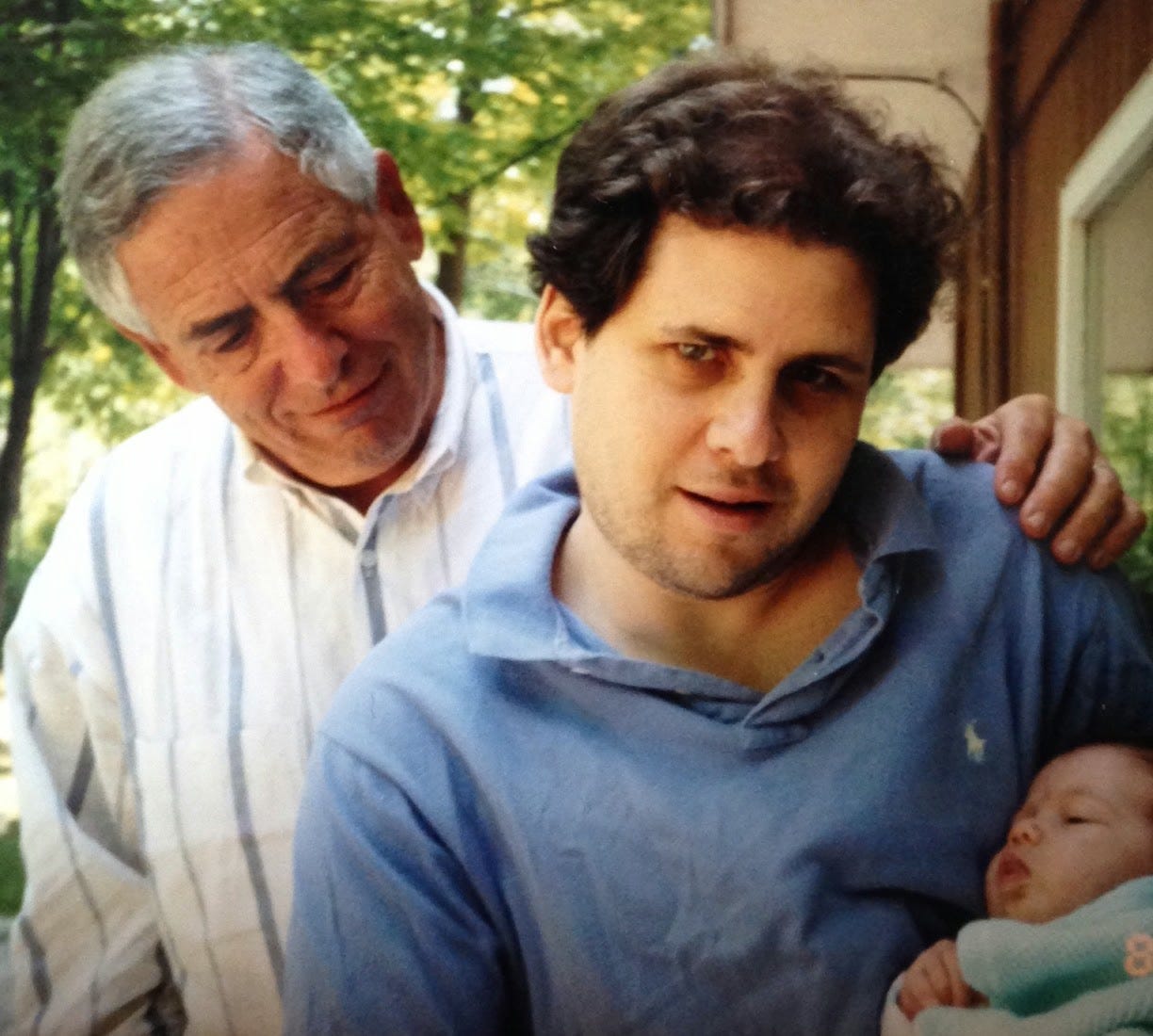

My late father, Jim Alter, who died in 2014 at age 92, would have been 100 years old today, and I wanted to use this occasion to tell you a little about him and his life in what Henry Luce called the American Century.

Anyone born in the first quarter of a century can properly be identified as a person of that century; those, like me, born mid-century or later (in my case, 1957) have a harder time doing so.

This is the kind of thing dad, born in 1922, liked to think about. He fought and nearly died in what was not only the major conflict of the century but the largest and most destructive war in human history—quite a distinction, when you think about it, though one he would chalk up mostly to happenstance. But he was also quietly connected to many of the other dizzying changes of the century, none more significant, he believed, than the change in the status of women, which he experienced firsthand in the political career of my mother, Joanne Alter, who died in 2008.

From time to time, dad would quote Thoreau saying, “most men lead lives of quiet desperation.” He didn’t seem to be one of them, but he sometimes sold himself short by claiming that his life didn’t really begin until he met Joanne, who was a force of nature across several realms. Quoted under a pseudonym in a book about American men, he confessed to sometimes feeling like an appendage— “son of, husband of, father of.” But overall, thanks to good fortune and a powerful sense of denial when bad news descended, he led a happy, family-focused life—and knew it.

Dad, who spent most of his adult life as a civically-active Chicago businessman, once told me that if he had to do it all over again, he might have done so as a history professor, preferably at a liberal arts college like Dartmouth that was near good skiing. When I was in kindergarten, he taught me to say—actually sing—the presidents in order and delighted in telling people that I was the only historian who didn’t know how to read. (He later memorized all the vice-presidents). After retiring, he taught business skills to working class kids, but his heart—like mine—was in American history. To illustrate how young America is, he liked to make what he called his “two-handshake” point:

Dad would explain that as a kid growing up on the South Side in the 1920s, he would attend Fourth of July parades and occasionally get to shake the hand of an octogenarian Civil War veteran. Dad pointed out that this old man, born around 1840, could have shaken the hand of an octogenarian veteran of the Revolutionary War, born about 1760. A third handshake—between dad and one of his grandchildren born around 2000 and the beneficiary of modern medicine—could extend the chain from the French and Indian War until the 22nd Century.

To give a sense of the pace of change in the first half of his life, dad noted that he was born five years before Charles Lindbergh was the first to fly across the Atlantic. Just 42 years later, with dad not yet fifty, men walked on the moon.

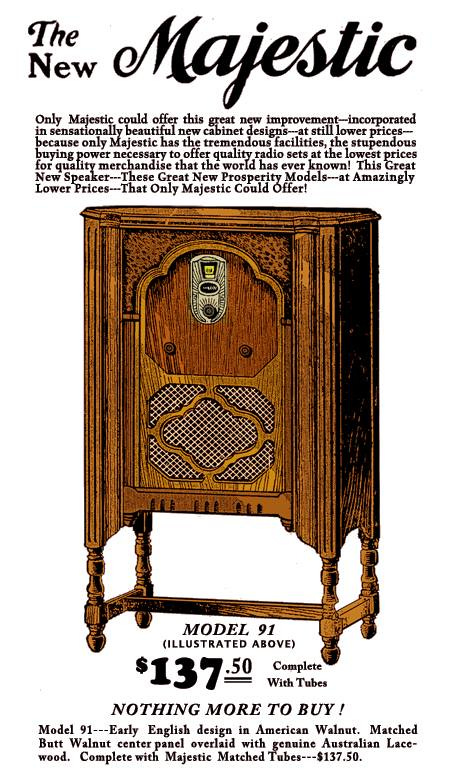

When dad was a little boy, his family was rich. His father, Harry Alter, the entrepreneurial son of Hungarian Jewish immigrants, made a fortune as the top distributor of Majestic Radios—“the Mighty Monarchs of the Air.” Radios in the ‘20s were like many personal computer brands in the ‘80s—selling like crazy before flopping. I have a 1928 invoice from the Harry Alter Co. to “Benito Mussilini (sic), Rome, Italy” for a $167.50 radio. (Mussolini was enormously popular then, in both Italy and the U.S., so there was no shame in it). But the following year, Majestic looked too frothy and my grandfather told his father—a glass lamp-maker— that he wanted to sell his stock. “Never sell America short!” my great-grandfather told him and the Alters were nearly wiped out in the Crash, though Harry bounced back some during the Depression by going into refrigeration and air conditioning parts.

In the Thirties, my father was drawn to the life of the mind, thanks to the influence of Robert Maynard Hutchins, who had become president of the University of Chicago at age 30. Hutchins allowed high school students at U-High (the high school connected to the University of Chicago) to take college classes, which gave dad a terrific liberal arts education and generated his line to me that “the best intellectual stimulation is as good as sex.” As a 17-year-old, dad was also a scrub on the last and miserably bad University of Chicago Big-Ten football team (e.g. they lost 85-0 against Michigan), which Hutchins famously abolished in 1939 as incompatible with academics.

Harry Alter insisted his son go to Purdue to study engineering in preparation for entering the family business (which most good sons did in those days). But after Pearl Harbor interrupted his sophomore year he enlisted in the Army Air Corps—the predecessor to the Air Force—and was commissioned as a lieutenant. After two and a half years of training on various bases, he shipped out in September of 1944 for southern Italy. Dad’s engaging memoir, From Campus to Combat, Stephen Ambrose’s The Wild Blue, which chronicles George McGovern’s very similar wartime exploits from a base just a few miles away, and the 1990 film Memphis Belle do the best jobs of telling the harrowing story of the Fifteenth Air Force’s strategic bombing of Nazi-occupied Europe. Dad was the bombardier and—after a crew mate was killed on a different mission— the navigator of a B-24 Liberator.

His experience was right out of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, where the brass keep raising the number of required missions before aviators could go home. When my three siblings and I were little, he didn’t want to scare us so he rarely talked about his 31 hair-raising missions unless we asked him specific questions, like how he went to the bathroom (Answer: he’d open the bomb bay doors and do his business from 25,000 feet). Later, he offered details, with gallows humor and disdain for braggarts and chicken hawk right-wingers who dodged service and drafted kids (“That’s what we were!”) to go die for abstractions. Before his book was picked up by a small publisher, he had it privately printed under the title, We Were So Young.

Dad and his crew mates were always happy to see Tuskegee Airmen flying fighter escort when they entered Nazi-held territory. They were based elsewhere—the army was still segregated—but highly regarded and when he heard them on his radio yelling, “Motherfucka at twelve o’clock [straight ahead and above]!” he knew the approaching Messerschmitt was going down. By late in the war, the dog fights with the Luftwaffe were mostly over. Flak from anti-aircraft artillery was a much bigger problem, as the German lines receded and the Nazis moved more of their mobile 88s closer to the military targets dad was bombing. His plane would often return to base badly damaged and he would pick the shards of metal out of his flak jacket. After the war, it was determined that the B-17 crews flying out of England had the highest casualties of the war—significantly higher than the infantry. Second were the B-24s out of Italy. On many days, dad saw other planes blown up. On many nights, he went to sleep looking at empty cots.

In early 1945, dad’s B-24 was so badly damaged that the plane was forced to make an emergency landing. Dad’s orders were to pull out his .45 and put slugs into the Norden bombsight, the highly classified primitive computer that was in his care. (He later learned the Germans had long since recovered one so the secrecy was pointless). When the airmen saw Soviet soldiers rushing toward them, they breathed a sigh of relief. After a night of hard drinking with the Russians, the crew exchanged the wreckage of their aircraft for cartons of cigarettes and safe passage through Soviet lines back to Italy.

Dad was often asked why he and other airmen didn’t bomb the concentration camps. His answer was that perhaps they should have bombed more railroad mustering yards but the bombs weren’t accurate enough to take out rail lines and the ones they managed to hit on other missions were quickly rebuilt. Bombing the camps themselves would have just killed prisoners, and at that point they had no idea about the ovens. If their superiors knew, they didn’t tell them.

On April 12, 1945, dad wept through his oxygen mask on hearing the news of FDR’s death. With the war in Europe over, he was dispatched to California to prepare for the invasion of Japan, which was estimated to cost more than half a million American lives. The dropping of the atomic bomb (the one on Hiroshima; the Nagasaki bomb was unnecessary) may well have saved dad’s life.

Back home, his family asked him about his bombing targets. When asked if any were in Hungary, he said yes. Did he bomb a town called Hatvan? Dad said yes, he remembered a target in that town. “That’s where our people are from,” my great-grandmother, Minna Alter, told him. They soon learned that by the time dad bombed the place, the local Jews had all been deported to Auschwitz.

Dad didn’t seem to suffer any after-effects of combat, and he quickly forgave Germans. In the ‘60s, he bought a Volkswagen Beetle convertible and in the ‘70s he treated a German exchange student, Matthias Scholz, who lived at our house, like another son. When dad died, Matthias—our lifelong friend—traveled all the way from Germany to Chicago for his funeral.

Dad wasn’t a pacifist but he was deeply anti-war. He refused to join the VFW or American Legion—most of whose members never saw real combat—and signed up for the liberal alternative, the American Veterans Committee. Beyond a brief weakness for a Nehru jacket and the occasional playful use of the word “groovy,” the ’60s didn’t hit dad particularly hard; unlike half their friends, my parents stayed happily married. But dad was all-in on the peace movement. He helped found a Chicago group of business executives against the Vietnam War and volunteered at the tumultuous 1968 Democratic National Convention for Gene McCarthy, the peace candidate for president, while mom backed Hubert Humphrey.

The biggest political disagreement I ever had with him came in 2003 when I reluctantly supported the Iraq War in my Newsweek column because—while I detested George W. Bush— I wrongly believed Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. He came out strongly against the war and was, of course, right. Given the fiasco that ensued, that was the low point (so far!) of my journalistic career. Back in Chicago, my parents raised money for an obscure young black antiwar candidate for Senate named Barack Obama.

Just after they were married, mom and dad had worked in the 1952 presidential campaign of Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson and they stayed politically active in all the years that followed, mostly fighting Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Machine. When I was ten or eleven, dad began bringing me along to various civic meetings. In the mid-1970s, he chaired the Governor’s Commission on Mortgage Practices, which did important work in making Illinois a model in combating redlining. In 1972, mom ran a highly-publicized early environmental campaign and became the first woman elected to public office in Cook County, as commissioner of the Metropolitan Sanitary District, (now Water Reclamation District). She later ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor and county clerk and was a well-known force in local politics.

If mom was a pioneer, dad had no playbook for how to be a supportive male spouse of a politician. Eight years before Denis Thatcher (and 50 before Doug Emhoff), he backed her to the hilt, with shrewd advice, no jealousy and a shoulder to lean on when she came under nasty attacks from Machine hacks. When they were first married, dad quit golf. He wanted to spend weekends with us, “rough-housing,” canoeing, going to Indian pow-wows and a million other excursions. In his basement workshop, he built elaborate Christmas presents (yes, as Jews we still celebrated it) like a wooden foos-ball set and a skyscraper with a small elevator to take my sisters’ dolls to the top. While he wasn’t fully evolved (he still barked at mom if she didn’t serve him his coffee and toast together), he spent the ‘60s and’70s as the model of a warm and attentive 21st Century father.

At his wholesaling business, he defied the bigoted and mobbed-up Teamsters local by hiring large numbers of black workers in his warehouse, including many ex-cons; he was especially forgiving of murderers who had served their time for “crimes of passion.” When the Teamsters went on strike against him and burned one of his trucks, he didn’t let it bother him. Everything he did was a little different, from putting reproductions of Impressionist paintings from the Art Institute on the cover of his air conditioning and refrigeration parts catalogue to riding his bicycle 10 miles to work most of the year, a form of commuting so novel in the ‘70s that one of the Chicago dailies devoted a full-page feature to it.

I could go on for a while about all the things he taught me, starting with how to write. In the evenings, he would bring home the old Chicago Daily News and we would chew over Mike Royko’s column. When I was a seven-year-old southpaw pitcher, he took me to nearby Wrigley Field to see two other Jewish left-handers —Kenny Holtzman of the Cubs and Sandy Koufax of the Dodgers—square off. (Holtzman won that day), and we saw Gale Sayers and Dick Butkus —as well as Johnny Unitas—play football in Wrigley.

In 1971, the Bears moved to Soldier Field, which was fine for a while but in the 1990s they decided on a huge, taxpayer-funded renovation. Dad was chair of Friends of the Park, a community group, and he thought the Bears were desecrating the lakefront. He spearheaded a long futile struggle against the rapacious owners and the politicians who coddled them.

By this time, his business had gone bust, thanks to changing market conditions and some bad decisions he made. He had chaired a couple trade associations and tried to innovate but he was basically miscast as a businessman, in part because he shunned the private clubs where deals are made and didn’t really give a shit about making money. Having invested everything in the Harry Alter Co., my parents had to sell their old Victorian house and tighten their belts considerably. But his denial mechanism kicked in and —to my mother’s chagrin—he was nonchalant about it, even writing an article somewhere entitled, “Why Chapter 11 Isn’t Your Last Chapter.” He spent his later years writing a novel and a mystery that didn’t get published and doing nice things for people. When he learned that the gay son of a business associate was estranged from his homophobic father, he took him under his wing and won a close friend for life.

Dad fell in love with the mountains, as more Jewish men than you might imagine have done. While he chaired a Jewish charity, he despised tribalism in all its forms and was more interested in the American West than the West Bank.

Just after the war, dad had gone to Aspen, where he passed up a chance to buy what would now be a $20 million Victorian house for $500 in back taxes. In those days, he skied on 210cm stained wood skis with bear trap (no release) bindings. With better equipment and good health, he skied until he was 80, often by himself, with a hip flask for company. My memories of our time on the slopes are some of the best I have.

After he died, our family planned to spread his ashes on Riva Ridge at Vail, one of his favorite runs. That was prohibited, so we had to settle for the deep snow in someone’s yard. In a scene out of Meet the Parents, his ashes got all over me, and stayed on my boots for years. That was just fine. I’d always hoped a little of dad would rub off on me.

What a lovely tribute to your dad. What a great dad (& son)! Thank you.

Lovely reminiscence, Jon. I have only a few memories of meeting your dad, but they are all very pleasant.