Trump Saw Hate as a Civic Good

Ruminating with The New York Times' Maggie Haberman, author of "Confidence Man, The Making of Donald Trump and the Breaking of America"

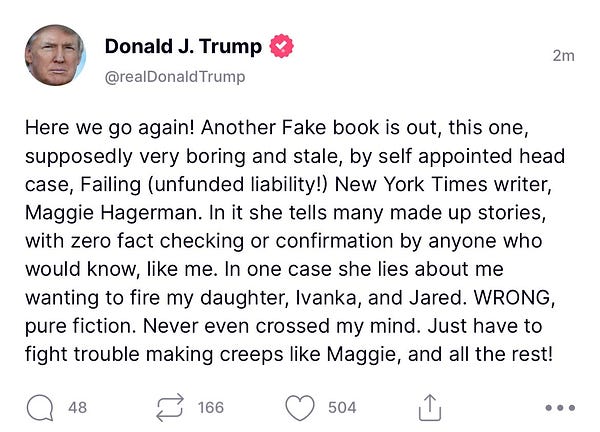

At 48, Maggie Haberman is not close to being an old goat, but I’m making an exception this week because her new book, “Confidence Man: The Making of Donald Trump and the Breaking of America,” is so good that I wanted to talk to her about it. Maggie has covered Trump longer and better than anyone. She was born and raised in New York, where her father, Clyde Haberman, was a top reporter for “The New York Times,” and her mother, Nancy Haberman, a well-regarded publicist. I know both of her parents but didn’t know Maggie when she worked at the New York Post, the New York Daily News and Politico. I got to know her some when she moved to the Times. I like that she covers Washington from New York, which I did for many years at Newsweek. It sounds weird but as long as you visit a lot, it gives you some depth perception that’s harder when you’re caught up in every Beltway intrigue.

My favorite parts of the book — now number one on the nonfiction New York Times Bestsellers List — are the ones dealing with Trump in New York. I first moved there in 1983, when Trump Tower had just opened. I was covering national and global events for Newsweek but did have a couple of memorable interactions with Trump over the years. In 1991, I appeared from my extremely messy office in a critical documentary, Trump: What’s the Deal?, and he threatened to sue me and others, though of course he never followed through. (He squelched the film for 26 years until it was posted on YouTube in 2016).

In 1997, I interviewed him in Trump Tower for the TODAY Show and I attended a Trump rally in New Hampshire in 2016. In 2018, I co-directed a documentary, Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists, that blasted Trump for calling for the death penalty for five Black youths who were later cleared of charges in the Central Park Jogger case (see below). Beyond constantly attacking him from afar, that’s about the extent of my connection to this despicable human being.

I have great respect for those whose job it is to cover him up close. The people who criticize them on Twitter have no idea how hard it is. This rumination is excerpted from an October 13th interview I did with Maggie on stage as part of the Open Book/Open Mind series at the Montclair (NJ) Public Library.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Welcome to Montclair, Maggie.

Trump recently re-raised the O.J. Simpson defense — that the classified documents at Mar-a-Lago were planted. He said the FBI planted a book on how to make nuclear weapons. We all know how Trump projects — how he accuses others of what he has done himself. These nuclear secrets are worth a lot on the market if you were to use an intermediary to try to sell them.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

There are a couple of buckets in which you could put the big thing we don't know about, which is why he had these documents.

One is what you just described, which is monetizing. That requires a level of competence and people around him who could execute that. That is a little harder to see at the moment, [but] not impossible. There are all kinds of people coming in and out of Mar-a-Lago.

[Another] is that he loves trophies. In Trump Tower he has a giant sneaker that was Shaquille O’Neal’s and in the White House he loved having the Kim Jong-Un letters as trophies. But ultimately so much of what he does and seeks is about leverage, and having leverage over someone else, or something else.

I don't know what that leverage necessarily is, but everything is about it: “What have I got that you want, and what can I use in some way?”

JON:

Trump he described you as his psychiatrist. What do you think he meant by that and how would you characterize your relationship?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I don't think he meant much.

He had this line toward the end of the last interview in September 2021, and he said [to others in the room], “I love being with her. She’s like my psychiatrist.” This was when he was sort of [venting] about something.

And what I write [in the book] is that it was a meaningless line. The reality is, he treats everyone like they are his psychiatrists, because he is working everything out in real time, all the time. As for [our] relationship, I think that's the wrong word. He's a subject who I cover. I covered Hillary Clinton and I covered Mike Bloomberg and I covered Rudy Giuliani. It's just different with him because he interacts with news coverage so differently, and he has such a specific fixation on The New York Times. I'm just the person who covers him most often for the Times.

JON:

Ben Smith made an interesting point — that he needs you more than you need him.

One thing we were talking about in the green room that people who are not journalists don't understand, is that getting access to “the principal,” as we’ll call elected officials or Cabinet secretaries — whether it's President or someone else — is not all it’s cracked up to be. You don't really need their quotes. And when you do find something newsworthy, contrary to some bullshit on the Internet, you put it in The New York Times in real time, when he makes news, which isn't that often.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I do understand that people don't understand it, or have misconceptions of it. I think one of the worst parts about Twitter is that a lot of people get not only their news from Twitter these days, but they get their understanding of journalism from Twitter and there are a lot of misconceptions about the profession and about the way journalism works, particularly with Donald Trump. There is always going to be a spectrum of what you're likely to get out of Trump.

You’re guaranteed that it's not going to be truthful throughout much of it. [And] it is not necessarily going to be coherent throughout much of it, because he talks like this. [She rotates her hand in a circle]

[But] I will cover him whether he's talking to me or not. I don't need his permission to cover him and he's never actually understood that. He just fundamentally doesn't understand what journalists do.

When he said he would give interviews to all the book authors I thought, I’m not gonna get anything out of this. And then when I went down there he actually said much more [than I expected] because I was talking to him about New York and the past.

JON:

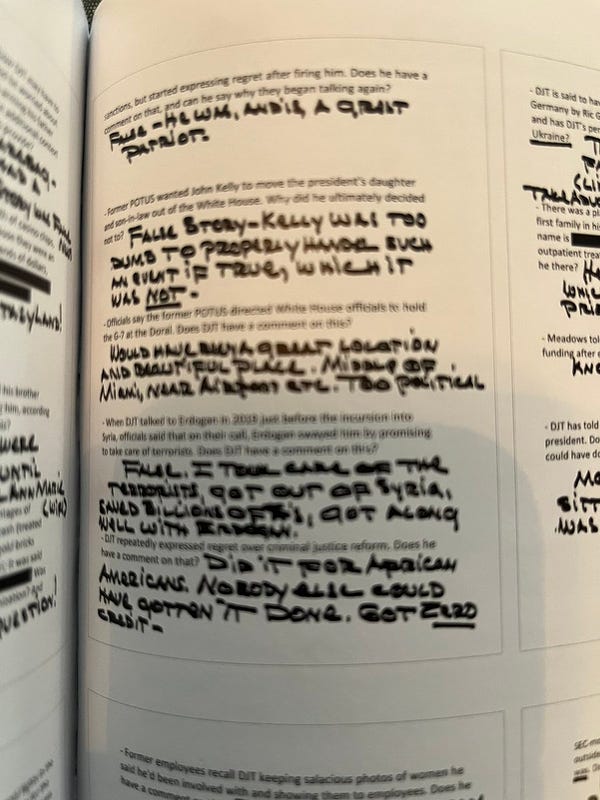

I thought it was great that in the photo section in the middle of the book you have his responses to some of your fact-checking questions. But my problem with it is that he lies every time he opens his mouth. He lies as easily as he breathes. So what is any of that actually worth journalistically?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

What’s the value? I think this is the question that we we struggle with daily, right? I mean he's now a former president. He's not Donald Trump the developer.

JON:

You can’t just ignore him, but that doesn’t mean the coverage has all been good.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

There’s been a lot of criticism of 2016 campaign coverage, and I think some of it is valid. But in the aggregate I think voters had a pretty clear sense of who this guy was.

But there could have been more on his business ties. That was a big under-explored area given that we just never had a president with these kinds of entanglements, particularly foreign entanglements. I think there is [legitimate] criticism of the media in terms of giving weight to his words in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s when he is doing all of this myth-making about himself and building this artifice — brick by brick — of himself as this massively successful tycoon commensurate with Jack Welch. Despite the fact that people knew that he didn't tell the truth a lot of the time, his statements just went unchecked— in some cases for years — and that, I think, is a problem now.

He's a former president, and he's got enormous sway in the Republican Party, and at least when it comes to a book about his life, he's still the only person who can answer some of these questions. So I felt the need to go to him.

JON:

My basic take on Trump — and I’m wondering whether this is yours as well — is that just when you think he's touched bottom, he crashes through the floor. Do you see the same progression?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I think you put it very well. I've never seen somebody whose desire to test the limits of transgressive behavior is as intense as it is with him. Every time you think that there is a limit — there is no limit. January 6th, 2021 really showed that.

JON:

We thought that was the bottom.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Then a few months later he starts fomenting this idea that his supporter, Mike Lindell, was spreading, that he was going to get reinstated at the White House.

It’s silly because there's no such mechanism. But there are supporters of his out there who don't realize that, and so it is something that is very dangerous to be engaging in and encouraging conservative writers to spread, which is what he was doing in 2021. When I reported this in real time that he was saying this I got a lot of blowback from people who said we should ignore him. I don't think you can ignore that. At this point, I think we've seen the impact of that kind of language from him. We should have ignored him when he was on the way up.

“We should have ignored him when he was on the way up.”

JON:

I'm a guilty journalist on this. He knew that New York journalists needed copy and he was always available. And he knew how to feed the beast — literally. I went over to Trump Tower in the ‘90s with an NBC crew and he had food for them. They loved it.

He might not understand journalism, but when he ran for President, he was the most experienced candidate in the thing that counts the most, which is the media.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

There is absolutely no question that his dexterity with being on TV was a huge value for him, and it gave him an enormous edge over everybody else. As much as he hates parts of the media, he loves it and needs it, and that was just a contrast to every other [2016 candidate] with the possible exception of Mike Huckabee.

He doesn't experience news coverage the way anyone else I've ever covered does. Stories that would humiliate other people, or they'd be embarrassed to have out there, he revels in. You know that famous 1990s New York Post front page headline that was allegedly said by Marla Maples—“The best sex I ever had”? He loved it.

JON:

One of the great things about your book is that you give the back story of all the New York stuff — in that case, an editor at the New York Post basically concocted that whole thing out of nothing.

I'm interested in his mentors— people that he modeled his behavior on. We know his reverence for his father, who was arrested at a Ku Klux Klan demonstration in 1925, which gives you some idea of what Fred Trump was like.

Let's talk about what he learned from some of the others. Roy Cohn.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Roy Cohn becomes Trump's lawyer in 1973, when Trump and his father and their business were being sued by the Justice Department for racially discriminatory housing practices. Cohn tells Trump to fight like hell and Trump learns a couple of things. One is the you can use the court system interchangeably with public relations. You can shout as loud as possible, and try to keep whoever's challenging you at bay for a while that way. You can threaten and intimidate and menace, and even if you settle, you won't say you're settling. And most specifically, he learned that the role of a lawyer could be turned into something almost like a mafia don.

JON:

Or did he turn himself into a mafia don? I mean, he basically gave three apartments in Trump Tower to the mistress of a big mobster, and he flew John Gotti's top lieutenant on his helicopter Atlantic City, and then later claimed he didn't know the guy.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

The mafia was deep into the concrete industry in New York City, which was the material that Trump chose to build Trump Tower with, and then he had interactions with Mafia-linked folks when he was doing his [Atlantic City] casino projects. He certainly adopts those kinds of behaviors. Michael Cohen talks about this all the time — that Trump sort of speaks in a code, and gives you a sense of what he wants you to do without openly saying it.

JON:

He never puts anything in writing and we know that he adopted this character, John Barron [he named his son Barron], where he pretends to be this other guy on the phone. But I learned from your book about a guy named Vinnie I had never heard of before. Who was Vinnie?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Trump was in the middle of trying to get a tax abatement for Trump Tower and the housing commissioner in New York City, who worked for [Mayor] Ed Koch, rejects the tax abatement. He gets a call at his home one morning from someone who identifies himself as Vinnie and Vinnie is very upset that Mr. Trump is not getting his tax abatement, and there’s a threat. [The commissioner] reports this to officials and is given a security detail. It was, I think, the next day [when] Trump himself claims he, too, got a threatening call. There's no hard proof of who “Vinnie” was, but there is widespread [suspicion] that it was Trump himself. The way this story ends is that Trump gets the tax abatement.

JON:

And hires the commissioner at his company — if he agrees to lose weight.

Another person he modeled behavior from: George Steinbrenner [owner of the New York Yankees].

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Steinbrenner was this avatar of hyper-masculinity in the 1980s. When the AIDS era was beginning, Trump was terrified of AIDS and talked about it all the time, and after shaking hands with men, would call reporters and say, “Is blah blah blah gay? I just shook hands with them!” Steinbrenner was a big, tough guy, also a child of privilege, like Trump. He had a healthy dose of self regard, like Trump, who hung around him and his crew and found himself emulating this hyper-masculinity.

Steinbrenner was famous for firing his managers, except he wasn't doing it by play-acting. When Trump, who really doesn't like firing people directly, starts doing “You’re fired!” on “The Apprentice.” it was pretty widely seen as homage to Steinbrenner. That show changed everything for him.

JON:

How about a man named Meade Esposito. Who was he?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

When machine bosses ruled everything in New York City, Trump's father, Fred, was very close to Meade Esposito [the Brooklyn boss] and that helped them hardwire all kinds of projects in Brooklyn. Meade had enormous clout all over the city, and he was a criminal. He did not believe that rules and regulations applied to him.

He made judges, He made district attorneys, and when Trump came into office [the presidency], he would talk about a figure who sounded very much like Meade, and aides had no idea who he was talking about because most of his officials weren't from New York. He would talk about Meade swinging his cane at people. Trump said Meade ruled with an iron fist. He informed Trump's idea of how a political operator functions and rules, which is just top down. And Meade fit Trump's idea of strength. A lot of Trump's idea of strength is informed by violence, which [he thinks] makes you strong, and that, in turn, [defines] what makes a good boss.

JON:

Like a Tammany Hall view of the presidency.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Correct.

JON:

Let’s talk about more of his most despicable qualities. Tell us what happened after the helicopter crash?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

A bunch of Trump executives died in a helicopter crash in New Jersey, I think it was on their way back from a meeting at Trump Tower. Two things happened afterwards.

One was that somehow a [gossip] item got placed suggesting that Trump himself was supposed to be on this helicopter, which nobody believed. [The widows] were really aghast at this suggestion that Trump himself was somehow in danger. And later on he started to blame his financial woes at the casinos on one of those dead executives. He says to one of his officials, Jack O'Donnell, “You know he's dead. What does it matter what I say about him now?” That really stayed with O'Donnell, who wrote his own book. In all of these descriptions, people who have been around him for a very long time say he just has a chronic disregard for other people's feelings.

JON:

So you say that he actually doesn't have that many moves, and he uses them over and over again, in part because he understands the value of repetition, which is very important in politics, and which the Democrats don’t understand.

So the overall move that he has is repetition. But then there are some specific moves, and I wanted to go over them and see if you could give us an example of each.

The first one you mention is “the counter-attack.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

That’s Hillary Clinton calling him a puppet of Putin, and he says, “No, you're the puppet!”

JON:

“The quick lie.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

In one of our interviews I asked him what he was doing during the January 6th attack and he said that he wasn't watching television, and that he rarely had the TV on.

I mean, there are so many on those. “It's my campaign manager's fault that I'm losing.” Finding some aide to to shoulder whatever crisis is going on because nothing is ever his fault.

JON:

“The distraction.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Right after the [2016] Republican National Convention, he [gets criticized for] comments about Russia [finding Hillary’s emails] and suddenly these nude pictures of Melania Trump show up on the front page of the New York Post from a decade earlier. Trump appears to have no problem with this.

JON:

“The outburst of rage.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Well, I can lose count on that one. You see that all the time. The screaming at people to get them in line is something that he has done throughout his life. When he had just won, somebody who had worked for him years ago said to me, “He is a screamer, and people in the White House are gonna have a really hard time with this,” and indeed they did.

JON:

“The performative anger.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Some of the tweets that are all caps that we would all describe as him fuming. He would be laughing as he was sending them.

JON:

“Just for the headlines.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

“Obama tapped my phone” would be a good example of that one in 2017, with no evidence other than some Breitbart story that he was reading. But he knew he would get a headline out of it.

JON:

If you were breaking down his superpowers, what would they be?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

To pick up on other people's insecurities is one of them, and I think his shamelessness is another. It has been a huge edge in politics and in his business life. He is hyper-focused on the darkness of human emotions and he is really attuned to bad things people will do. He is aware that other people experience shame and he tries to press that, too. There's a power in shamelessness — a big one.

And he absorbed Roy Cohn's lesson that he articulated to [columnist] William Safire, which is that he brings out the worst in his enemies and gets them to defeat themselves.

JON:

You call his behavior on January 6th “indecisiveness, masked by compensatory lunge.”

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

This is gonna sound hard to believe, but after he lost on November 3rd he could not decide what course of action to follow.

When it became clear that he was not going to be able to stay in office anymore, he was quizzing everybody, including the valet who brought him his Diet Cokes: “What do you think I should do?” And then, after it becomes clear that he's not quite ready to pull the trigger on this proposed government intervention [impounding voting machines and declaring martial law] that Mike Flynn is telling him they should do, he suddenly seizes on January 6th, and throws all of his energy into it.

JON:

Why does so little stick to him? Why is he the ultimate Teflon president?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

A couple of things. I think the fact that he was part of the pop culture fabric for so long— and part of this does relate to “The Apprentice”— what became clear in 2016 was that his voters felt very bonded to him in ways that they really didn’t to previous candidates. There was this huge desire to win and voters were willing to overlook a lot, and then they got in the habit of overlooking all kinds of things. During the presidency, everything was treated as if it was a four-alarm fire. When everything is an emergency, then voters start to feel like nothing is.

JON:

What do you think was the most blown out of proportion and harmful to the Democrats when they made too much of it?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

So kids in cages and the humanitarian crisis at the border was a big deal, but many other stories were not. Not every single tweet [needed to be covered]. Every tweet, every gaffe, every nonsensical answer was not the same. Congratulating Putin on winning his election when he'd been told not to — or praising Xi Jinping — that’s important. But not everything.

JON:

The anti-Trump conservative writer, David French, wrote recently about what he calls “the exhausted majority.” I thought it was a good line. People might be getting tired of the drama.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Now there are a lot of [GOP] candidates who are gonna run, and I think he’s taking on some water [on the Mar-a-Lago documents]. I don't think it's “nothing sticks to him” anymore.

JON:

How much are the walls closing in now?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I think he's really consumed by these investigations.

The documents investigation in particular is really scaring him.

The main proof that he is worried is that he paid a $3 million dollar upfront retainer for a lawyer whose advice he has completely ceased to listen to. But he was worried enough that he hired the guy.

He doesn't seem animated by the rallies the way he once did. They're really long with not a lot of new material.

We'll see. Maybe he'll get into it if he does become a candidate. I do think he has backed himself into a corner where he has to run, because the investigations oddly compel him forward. If he runs, he remains the overwhelming favorite to be the nominee, but that is obviously absent outcomes in these investigations, and I just don't know what that looks like.

JON:

On the question of race, one of your big scoops that came out a few months ago was that he was flushing documents down the toilet. But there's another toilet story in your book.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

There's a lot of Donald trump toilet stories.

JON:

Tell the one that really goes to his racial animus.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

So when he was first [elected], he would show me what he would call his secret bathroom off the Oval Office, and he would claim that he had renovated the entire space down to the toilet, which was not true according to officials. I think they they just customarily replace a toilet seat any time there's a new president. But he would show this space, and he would say, “You understand what I'm talking about?” It was a very strange remark, and open to interpretation.

One guest who heard it interpreted it as him not wanting to use his black predecessor's bathroom, and you know there's just a lot of that with him over a very long period of time.

JON:

Some of the big public things like birtherism were racist. But you have other private details.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

Just before dating Melania, actually overlapping with her, he had a half-Black girlfriend. Her father was white and mother was Black. He met her parents and he told her that she got her beauty from her mom and her brains from her dad on the white side.

JON:

How much do you think he accepts that he lost the election?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I don't think he accepts it at all. It seemed pretty clear to people right after the election that he knew that he had lost. He seemed almost apologetic to some of them. I think he was clear that it was over, and then he decided it wasn't.

JON:

Do you think this is in some ways no longer fake on his part?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

It's very possible that he has convinced himself that he really did win. This goes to the repetition point, which is that if you say something often enough, people believe it, and it becomes “true.” That's true of himself, too.

JON:

Ivana Trump said that he kept Hitler’s Mein Kampf on his bedside table. And others have said he had a book of Hitler’s speeches.

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I don't think he read them, but I think that he has had a fascination with Hitler for a while.

JON:

Do you think Trump is evil?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

That's a really hard question to answer. I think that he is comfortable enough with behavior that is evil, and that's probably about as far as I can assess that.

JON:

I’ll answer the question: Yes. The subtitle of your book is “The Making of Donald Trump, and the Breaking of America.” What did he do to break this country?

MAGGIE HABERMAN:

I think that he did not create the partisanship but he fueled it and he exacerbated it and he benefited from it and he exported it.

In New York City in the ‘80s during a terrible case of violence [The “Central Park Jogger” case], in which five teenagers of color were arrested [for a crime they didn’t commit], he took out an ad calling for the death penalty for them.

He clearly saw hate as a civic good, and I think he exported that to Washington, and he has exported it to his party, and that has had a massive trickle-down effect.

JON:

I think that's a good, if depressing, place to end. Thanks, Maggie.

And exceptional interview. Thank you for publishing.

Thanks, Susan!