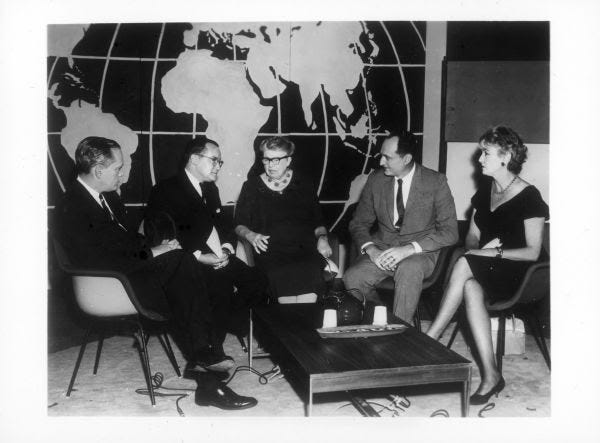

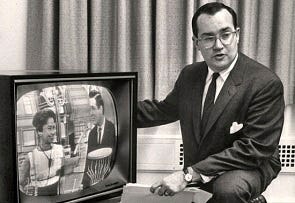

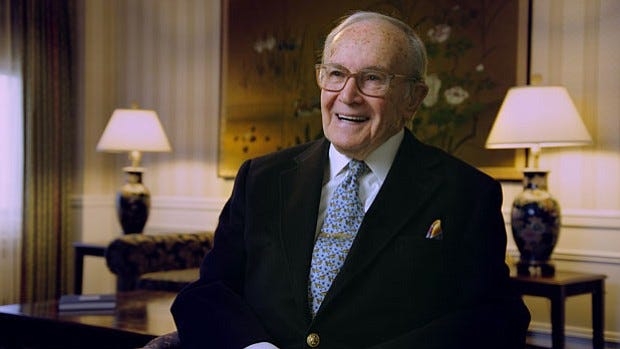

Ruminating with NEWTON MINOW

Obama mentor, founder of presidential debates and the last living JFK appointee, on the 60th anniversary of his famous speech about the “vast wasteland” of television

I’ve known Newt Minow for most of my life—my parents were old friends and neighbors and he has been an invaluable source of counsel to me and so many others. He is the last link to the Democratic Party of Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy and knew both men well, which we talk about.

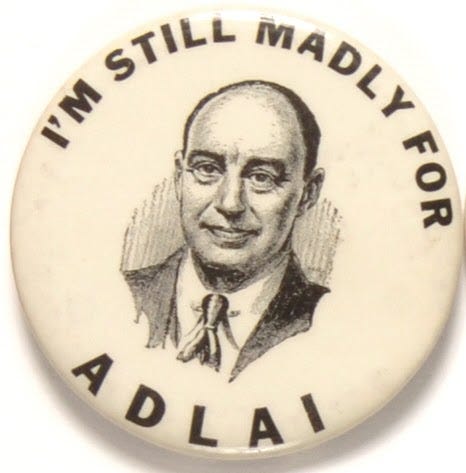

Now 95 and in astonishing physical and mental shape, Newt was a Jewish kid from Milwaukee who clerked for Chief Justice Fred Vinson (also Harry Truman’s poker buddy) before settling in Chicago and working closely with Gov. Adlai Stevenson of Illinois. In his late twenties, he became an important adviser in Adlai’s 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns (both of which he lost to Dwight Eisenhower).

“When television is good, nothing—not the theater, not the magazines or newspapers—nothing is better. But when television is bad, nothing is worse.”

Newt was instrumental in setting up the famous 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates and, in the 1980s, in establishing the Commission on Presidential Debates, which has sponsored all general election debates since 1988. (Needing some input from political reporters, he included me in the 1985 conference at Harvard that led to the formation of the commission).

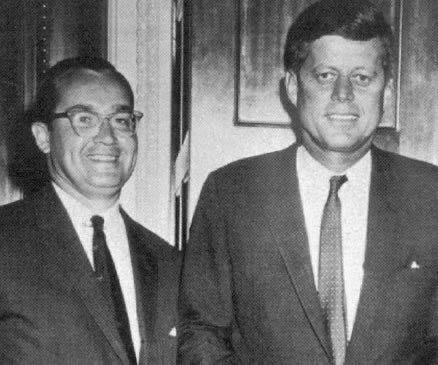

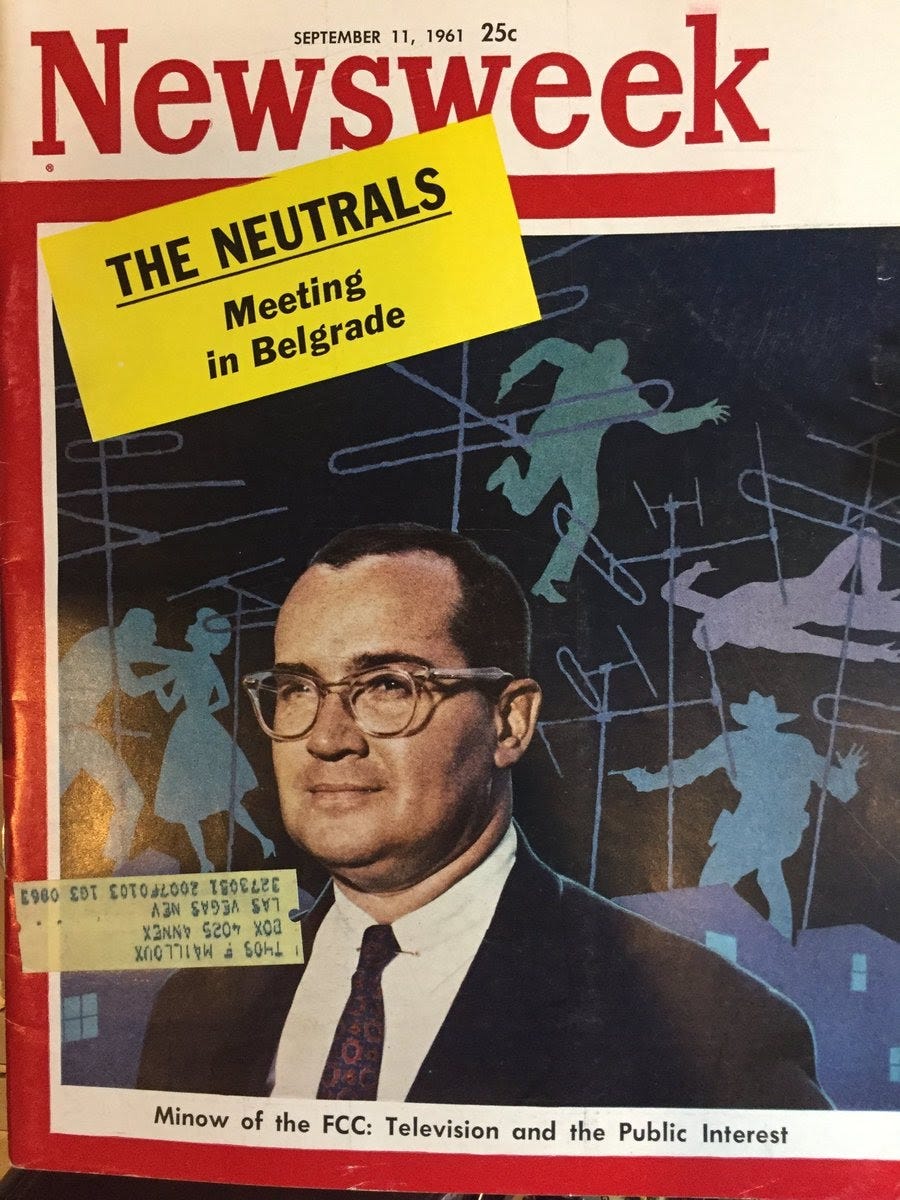

A friend of Bob Kennedy (real friends didn’t call him “Bobby”), Newt won appointment at 35 as JFK’s chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. His May 9, 1961 speech to the National Association of Broadcasters is the most famous ever delivered about TV, and worth reading or listening to for anyone interested in the history of television. The speech was entitled, “The Television Industry and the Public Interest” but it has long been remembered as “The ‘Vast Wasteland’ Speech”:

LISTEN TO AN EXCERPT from Minow's "Television in the Public Interest" speech to the National Association of Broadcasters (excerpt starts at 25:00)

“When television is good, nothing—not the theater, not the magazines or newspapers—nothing is better. But when television is bad, nothing is worse. I invite each of you to sit down in front of your own television set when your station goes on the air and stay there, for a day, without a book, without a magazine, without a newspaper, without a profit and loss sheet or a rating book to distract you. Keep your eyes glued to that set until the station signs off. I can assure you that what you will observe is a vast wasteland.

You will see a procession of game shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western bad men, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons. And endlessly, commercials—many screaming, cajoling, and offending. And most of all, boredom. True, you'll see a few things you will enjoy. But they will be very, very few. And if you think I exaggerate, I only ask you to try it.”

The speech worked its way into popular culture. On “Gilligan’s Island,” the shipwrecked boat is “the S.S. Minnow.”

JON:

Hi, Newt. Thanks for doing this.

NEWTON MINOW:

Happy to.

JON:

I know the broadcasters were very upset with the speech. But how did the Kennedy White House react?

NEWTON MINOW:

They liked it, though around that time a White House aide [Ralph Dungan] called to say, “We want you to hire Jews but not all Jews.” I said, “Listen, it takes one to catch one.” Sarnoff [David Sarnoff, the founder of NBC] is Jewish. Paley [William Paley, the founder of CBS] is Jewish. Goldenson [Leonard Goldenson, the founder of also-ran ABC] is Jewish.

JON:

Wow, that took some nerve for him to do that when his boss’ father was the famous anti-Semite Joe Kennedy. I guess that was just standard in those days, huh?

NEWTON MINOW:

Not uncommon. No offense taken.

JON:

With the recent deaths of Jean Kennedy Smith, Harris Wofford and Mortimer Caplin, JFK’s siblings, senior White House aides and agency heads are all dead except for you. So you’re one of the only people alive who can answer this: What was John F. Kennedy like? A cool guy?

NEWTON MINOW:

I was in love with JFK from the day I met him in 1954 when he came to Chicago to see Sarge (Sargent Shriver) and Eunice(JFK’s sister). He was very intelligent, had a helluva sense of humor and he was telling us we should be in public service. I immediately said to myself, this guy should be a candidate some day for president.

JON:

Ben Bradlee told me once that Obama was the first person to come along who reminded him of Jack Kennedy.

NEWTON MINOW:

I thought the same thing when Jo [Minow’s wife] and I saw him [Obama] campaigning at a fish fry in Iowa.

JON:

But you didn’t think he might someday be president when you hired him in 1989 to be a summer associate at Sidley Austin in Chicago. [where he met Michelle Robinson].

NEWTON MINOW: No. I thought of him as being a potential mayor of Chicago, maybe. Saw him as governor of Illinois and as president as he developed and grew.

JON:

When Kennedy impressed you in 1954, what did you do?

NEWTON MINOW:

I pushed very hard for him to go on the ticket in ’56 with Adlai.

JON:

Why did Adlai throw the vice presidential nomination open to the delegates?

NEWTON MINOW:

He thought it would provide some excitement and activity for the convention. And he couldn’t make up his mind between Humphrey and Kennedy. But the delegates voted for Kefauver and that was very disappointing.

JON:

Was Stevenson too indecisive to be president?

NEWTON MINOW:

He wasn’t indecisive at all about the issues but he was very indecisive about people and about his own career.

JON:

Reading Evan Thomas’ terrific book, “Ike’s Bluff,” got me thinking maybe it was better Eisenhower was president in the ‘50s because Adlai might not have been able to stand up to the military the way Ike did.

NEWTON MINOW:

Not necessarily. In 1962 when we had the Cuban Missile Crisis Adlai was very, very tough on the military. He told Jack, ‘Don’t listen to those guys.’

JON:

The liberals who were “Madly for Adlai” were not like the progressives of today, right? The center of gravity in the Democratic Party was more moderate in the 1950s and 1960s.

NEWTON MINOW:

That’s absolutely correct. The Democratic Party was centrist. It didn’t have anyone like Bernie or AOC, or at least not anyone of consequence. Politics was different then. More fun. Adlai had a great sense of humor and a sense of idealism, and he was a terrific speaker.

The best speech he ever gave was to the graduating class at Princeton and it was about the importance of everyone giving some of their lives to public service. People thought politics was a dirty business with low class people, no morals.

JON:

He elevated politics, and Kennedy built on that. Which brings us to JFK taking you up into the family quarters when he changed his shirt before addressing the broadcasters convention. What was that all about?

NEWTON MINOW:

Alan Shepard had become the first American in space just three days before and was in Washington to get a medal from Congress.

[Kennedy] decided to bring him to the broadcasters first. He brought me up to the Residence as he was changing his shirt. I knew him but was a little intimidated. He said, ‘What do you think I should say to the broadcasters?’ I said, “You want to tell them the difference between our way of doing things and the Russian way, between an open society and a closed one” where they hid their rockets that blew up. He doesn’t say yes or take any notes or anything.

“You want to tell them the difference between our way of doing things and the Russian way, between an open society and a closed one”

We go back downstairs, and I figured I'll get in the second car. And he says ‘No, no, no.’ So we're driving through Rock Creek Park up to the hotel with the president, me, the Shepards, and Lyndon [Vice President Johnson] on the jump seat.

JON:

He was a really big guy. That must have been awkward.

NEWTON MINOW:

The president was in a very up mood. This was only a few weeks after the fiasco at theBay of Pigs and now with Shepard’s space flight, there was something where we seemed a little ahead of the Russians.

So he slaps Lyndon on the back and says, “You're the chairman of the National Space Council. Nobody knows that you’re there but I guarantee you, Lyndon, if this space thing had been a failure, I would have made sure everyone knew.”

JON:

This was early in the term—the beginning of LBJ’s humiliation.

NEWTON MINOW:

When we get there, the president says perfectly with no notes what I had told him when he was changing his shirt—much better than I could. And of course the next day I delivered a very different speech—a wakeup call.

We had had terrible scandals in the broadcasting business—quiz scandals, payola scandals. I was particularly concerned with children’s television. The programs at that time were a disaster. And I wanted to get public television going.

JON:

Was it crickets afterwards?

NEWTON MINOW:

They did clap politely but weren’t happy.

JON:

It was like Edward R. Murrow’s speech to the RTNDA a couple years earlier about how if television doesn’t get more substantive and educational, “it’s just wires and lights in a box.”

NEWTON MINOW:

Murrow called that night and said, ‘You stole my speech.”

JON:

You both were concerned about something very current—that we’ve lost a sense of the public interest.

“Murrow called that night and said, ‘You stole my speech.”

NEWTON MINOW:

That’s right. The “public interest”—two words that are in the 1934 Communications Act (which regulated the public airwaves) 17 times. Nobody’s talking about the public interest today. At the time radio began, it was understood that if you were going to get a broadcast license, you have to serve your local community with good local news and reporting, and that if you were going to treat controversial issues, you have to treat them in a balanced way—what was called the Fairness Doctrine.

JON:

Which the FCC got rid of under Reagan. Should it be revived?

NEWTON MINOW:

Yes, I would restore the fairness doctrine which encourages broadcasters to cover controversial issues by presenting different views so listeners and viewers can make up their own minds.

JON:

Everyone assumes it’s impossible to get the toothpaste back in the tube with cable and the rest, but it could be done for broadcast radio and TV, which are still huge.

NEWTON MINOW:

The airwaves are public property. It used to be if you owned a station, you were seen as a trustee—a trustee for the public. Your license…

JON:

A license to print money.

NEWTON MINOW:

Your license would be reviewed and renewed on a three year basis, and you would not be renewed if you were not serving the public interest. That was the concept.

JON:

But you were pushing the development of UHF stations, PBS and other “educational television,” and early cable (to extend the reach into rural areas), and hundreds of new local stations--all to add competition and choice. Didn’t expanding television as much as possible make it harder to foster a “public interest”--harder to deny licenses to those not operating in the public interest, which you never did?

NEWTON MINOW:

There was one station in Jackson, Mississippi which actually lost its license when it wouldn’t let a black candidate for office on the air. Eleanor Roosevelt called me about it.

JON:

You started as an advocate of more choice, more options, but now you think that media fragmentation is a large part of what’s making us a more divided country, right? As you said in your brilliant preface to your daughter’s new book, we went from speech being scarce and the audience being large to speech being endless, and the audience, fragmented. So, what are the consequences of that shift?

“People are entitled to their own opinions but not their own facts. That’s the central issue facing us right now.”

NEWTON MINOW:

I do worry about that a lot. We’re a big country with a lot of people. The country needs things to bring us together and terrible things like President Kennedy’s assassination and 9/11 do that. Broadcasting makes it possible for 350 million people to share the same knowledge—the same experience—at the same time.

Now we no longer agree on what is a fact. We have people saying we can make up our own facts. Pat Moynihan said people are entitled to their own opinions but not their own facts. That’s the central issue facing us right now.

JON:

You were chair of the Rand Corporation board and they later issued a report on what they called “Truth Decay.” That retreat from the kingdom of truth pulls us apart.

NEWTON MINOW:

I’ve never seen the country as divided as it is today and I’ve lived a long time. This is more division than at any time since the Civil War.

JON:

And you think the problem goes beyond Trump, Fox and talk radio to a retreat not just from facts but some first principles.

To me one of the bad things that’s happened is people have forgotten that Martin Luther King said he wanted his children and grandchildren judged by the content of their character not the color of their skin. We should not say, ‘This job should be filled by a Black, or this one by an Hispanic, or this one by a White.’ We should treat people as individuals, not as groups.

“I’ve never seen the country as divided as it is today and I’ve lived a long time.”

JON:

Yes, but when you look at, say, police violence against black motorists—it’s never a white motorist who’s shot—King’s dream is still a long way from being fulfilled. Those cops sure aren’t judging the black motorists by the content of their character.

NEWTON MINOW:

I understand that, but just want people treated equally and judged as individuals.

JON:

You think woke culture on campus is a particular problem, right?

NEWTON MINOW:

When I was an undergraduate a Northwestern University in the late ‘40s, blacks were not allowed to live on campus. We organized a group and got that changed. Years later, when I was a trustee, students petitioned for an all-black dorm. I told them what had happened in the ‘40s and asked if I was wrong then. They said, “You were right then. But we are right now.”

Why are they right, now? I’m certainly not going to say to the whites, “You can have an all-white dorm.”

“Why are they right, now? I’m certainly not going to say to the whites, ‘You can have an all-white dorm.’”

JON:

Colleges and companies are afraid nowadays to make tough decisions. I like what Wesleyan President Michael Roth said when protesters tried to shut down the student newspaper when they didn’t like something in it: “Nowhere in the U.S. Constitution is there a right not to be offended.”

NEWTON MINOW:

I like that.

JON:

On the other side of the free speech issue--and we obviously need a balance--is a line I like from Rep. Tom Malinowski on regulating powerful platforms: “Freedom of speech is not freedom of reach.” In other words, no one has a right to be on TV or a social media platform. These are private companies and can be regulated. So what should happen with Section 230, which immunizes platforms against lawsuits over what’s on their sites?

NEWTON MINOW:

I certainly think 230 needs a thorough debate. At a minimum, Congress should say that if there is any violence promotion on your platform, you can be sued.

One of my daughters, Martha, who is a constitutional law professor at Harvard has written a book covering this issue and she’s smarter than I am.

JON:

If you could wave a magic wand, what should Congress do to deal with Truth Decay, divisions and these other problems?

NEWTON MINOW:

I think the most important thing is to improve our education system. Our firm is pro bono counsel in a very important case in Detroit arguing that a black child there has a constitutional right to a decent education. We need to provide that to everybody. That’s the most important thing.

JON:

Thanks, Newt.

Excellent Jon. No fair, I have to subscribe because of the scarcity of literate interviews these days. Jane

It's funny that you mention Dirksen and Douglas, Joel. They come up in a conversation I had recently that I will post before too long.