Ruminating with HENRY WINKLER

On "Barry," “the Fonz,” jumping the shark, and the fragility of being alive.

Henry Winkler is, by common consent, one of the nicest men in Hollywood. When we first met a few years ago, I felt as if I had known him forever, an experience I no doubt share with thousands of other people.

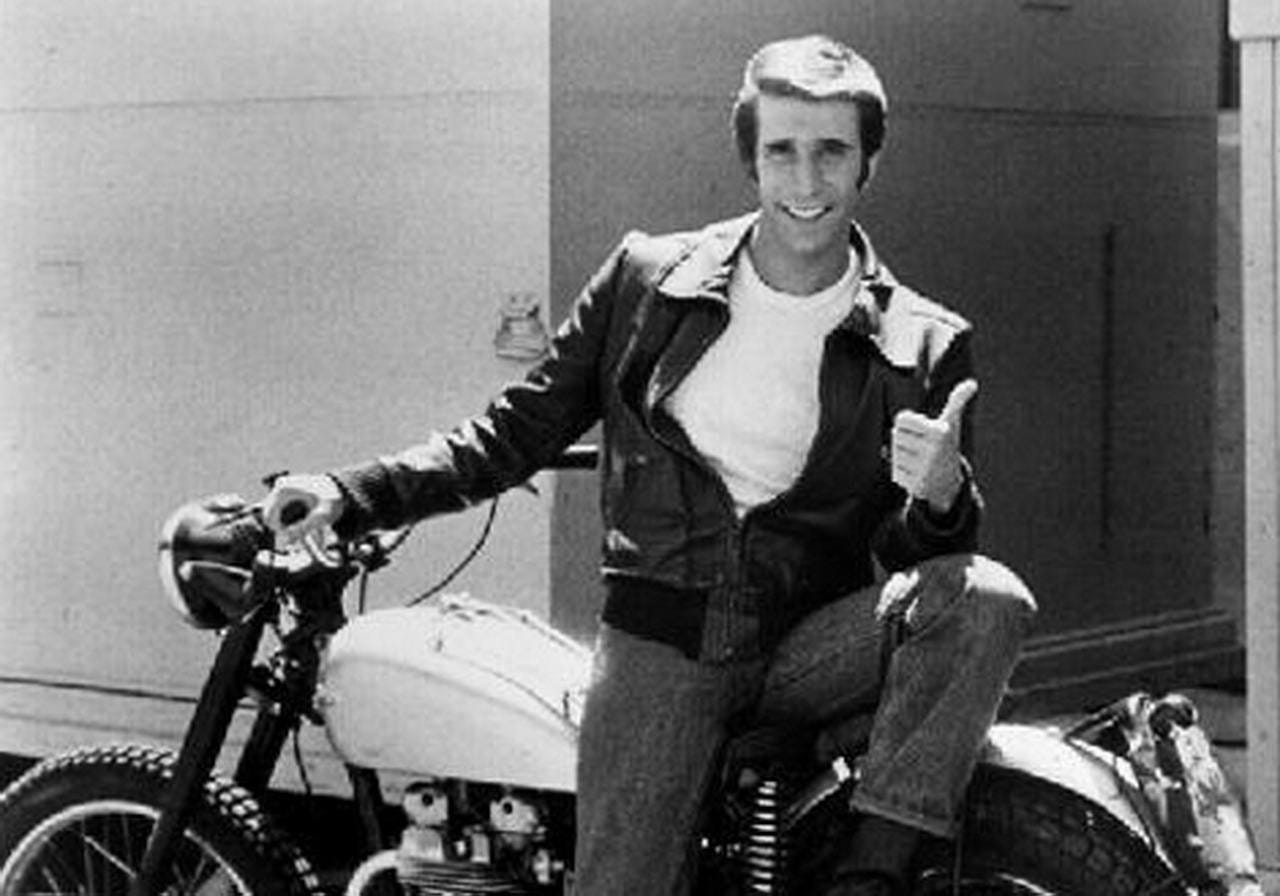

Born in New York, the son of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, Henry suffered from undiagnosed dyslexia. After degrees from Emerson and the Yale School of Drama, he broke out as Arthur Herbert Fonzarelli, nicknamed "The Fonz,” in “Happy Days,” one of the most successful sitcoms ever. Type cast, Henry couldn’t get acting parts for nearly a decade. So he produced and directed TV series and eventually returned to acting in “Arrested Development” and “Parks and Recreation,” among other shows.

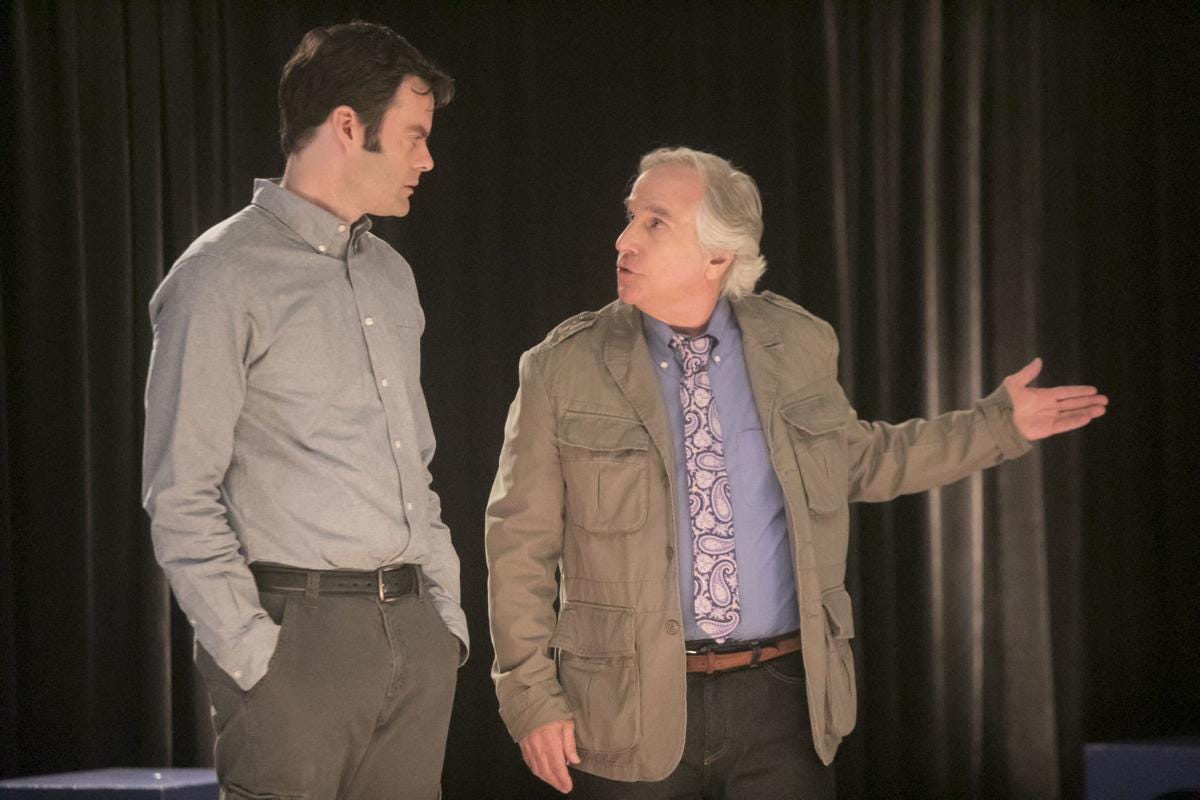

Henry won a Best Supporting Actor Emmy in 2018 for playing acting coach Gene Cousineau in HBO’s “Barry,” which I think everyone can agree needs to return ASAP with Season Three. Shooting on Season Four begins this summer.

JON:

Adam Sandler— underrated in “The Water Boy?”

HENRY WINKLER:

Adam Sandler is one of the five directing geniuses that I've worked with. He’s in charge of every detail for the entertainment that he creates. He is warm. He is shy. He's inventive and totally knows what he wants. Five films with him. And then he never called again— so actually he's a schmuck.

Mitch Hurwitz [creator of Arrested Development], Garry Marshall [creator of Happy Days]—also directing geniuses. Bill Hader and Alec Berg [co-creators of Barry] combined make brilliance.

JON:

What was the smartest, most memorable thing that [the late] Garry Marshall ever said to you?

HENRY WINKLER:

He taught me how to be on a set. He had time for everyone. One night, I was rushing to make my first personal appearance—I was going to get $1,000 to show up in Little Rock, Arkansas and sign autographs at the mall. I went up to him during the Friday night filming with members of the guest cast [smaller roles] and I said, “Can we hurry it up because I have to fly.” And he waited and then he put down the microphone, and he held me against the wall.

And he said, They [the guest cast] have every right to be introduced— just like you in the beginning. What he showed me was respect for the total of the ensemble behind and in front of the camera.

JON:

You had to treat everybody with respect.

HENRY WINKLER:

Everybody and anybody. And that became my life lesson.

JON:

When Garry Trudeau, Elliott Webb and I produced Alpha House, Amazon’s first show, in 2013, we really wanted a guy named Antoine Douaihy. He had been Mike Nichols’ line producer—the key guy in running a big production. When I went to recruit him at a coffee shop, he could tell I knew little about show business and was kinda looking at his watch and probably wondering, “Where’s Garry Trudeau?” I said “We [me and the other executive producers] are in our late fifties and early sixties and we want this show to be successful but we don’t need it to be successful, so we have a ‘No Assholes’ policy on our show.

Antoine looked up with a start and said, “You have a ‘No Assholes’ policy? I’ve been waiting 25 years for a ‘No Assholes’ policy! I’m in!!’ And he was terrific and didn’t hire anyone difficult in any production capacity and we didn’t cast any difficult actors and in two seasons with 125 people on our set, we had only one person who didn’t work out. John Goodman said it was the happiest set he ever worked on.

HENRY WINKLER:

Must be true. John’s a pretty straightforward guy. I’m in a project with him right now called “Monsters at Work” for Disney Plus.

JON:

Why did Happy Days become such a big deal? You had 30 million people who watched your last episode—an unimaginable number in 2021.

HENRY WINKLER:

I don't have an answer. What I know is Garry Marshall set the show in the ‘50s for a reason, so that when you watched it, it was ageless. The stories are relevant no matter when you watch it. They are family stories about the smallest details of what it is like to be alive on this planet. And each story had a moral but because it was set in the past, you never felt you were being hit on the head with a point of view.

JON:

Maybe to make something live a long time, it can't as easily be about the present.

HENRY WINKLER:

It has to be about the truth about being a human being and being alive, because honestly, we are all the same. And we all want and need pretty much the same stuff.

JON:

Isn’t that maybe a Pollyannish view of human nature? What do you mean by ‘We're all the same’?

HENRY WINKLER:

It is not a Kumbaya, I believe it's the very center, the very kernel of existing on earth. So let’s look at something that attracts a large number of people across hundreds of years. Somebody once said, a very long time ago, ‘Hey, I woke up this morning and I'm going to invent a piano.’ Then somebody said, ‘Wait a minute, I'm going to write music that you play on that piano.’ And then, 400 years later, there are people who say, ‘I can play that piano and that piece of music really well.’ And now I sit in the audience with an entire group of human beings, enjoying that experience and that same experience is enjoyed all over the world.

JON:

So no pun intended, there are just certain chords that you can strike that will appeal to all human beings. But to return for a second to our discussion of assholes: When do those things that we share get warped? I'm increasingly fascinated by what turns people bad.

HENRY WINKLER:

I think that being alive is so complicated. It is so fragile. I am 75 years old, and I finally understand there is no such concept as normalcy. There is only a lane, in which you exist, which you can travel down where you don't destroy yourself or anybody else. Something chemical can move you out of the lane. The way that you were treated at the very beginning of your life can move you out of that lane. Substance abuse can move you out of that lane. And believing you have a sense of power and want to hold on to it will pervert you.

Power is a mirage. People think you have it but if you wield it people get incredibly angry that you’re actually using what they think you have.

JON:

I interviewed a television anchor recently who said that fame for him was like crack cocaine. Do you agree? Does fame fuck you up? Does the camera fuck you up?

HENRY WINKLER:

I believe it’s fame, if you allow fame to be your reality. Power is a mirage. People think you have it but if you wield it people get incredibly angry that you’re actually using what they think you have.

JON:

Family’s gotta be relevant to not getting fucked up. You’ve only been married once. You seem like you've got a terrific family. You never sort of wigged out like so many celebrities.

HENRY WINKLER:

There’s always time for that.

JON:

You’re superstitious…

HENRY WINKLER:

I'm not superstitious, I’m dyslexic. I can’t even spell superstitious. And I think that a part of a learning challenge is there's something that's missing in my emotionality. When the Fonz hit, it was so big and it was so worldwide, I did not believe that what people were saying could possibly be true, because I had been told all my life that I was stupid and would never achieve. So now all these people are telling me I’m the coolest guy on the planet. That can’t be true because I’ve imprinted on the stupidity part. So I never absorbed it. I only saw it as a practical thing that allowed me to earn a living, and keep a roof over my head and my family’s and food on the table. I only saw it practically. I never saw it emotionally, which was good for me.

JON:

How do you function as an actor with dyslexia, having to read a lot of scripts?

HENRY WINKLER:

Let me just say, where there's a will, there's a way. If you want something, and you really want it, you will it, and you figure out how you're going to work around things to get it. And I just have to read scripts more often and very slowly.

We're going to see in August when I start “Barry” again. But [last season] I was able to read it, and then memorize it pretty quickly. You know, God giveth some and taketh away some. I’m going to find out if I can still memorize and my brain still works after a year and half of the pandemic.

JON:

So just to back up for a second to your family. Your parents barely escaped Nazi Germany in 1939 and they had you after they got to New York. Tell me about the box of chocolates your father brought with him.

HENRY WINKLER

Before he escaped, my father took the family jewelry and covered all of it in chocolate so it looked like pieces of chocolate. When he got to the checkpoint leaving Germany, he told the Nazis that he was taking nothing of value out of Germany. And thank God they did not check the box of chocolates under his arm.

He then pawned the jewelry in New York City, and was able to start their new life — with a company he brought from Germany that imported and exported lumber. He was able to buy the jewelry back, and my parents gave me my great grandfather's pocket watch that came out of Germany encased in chocolate.

When I was growing up, not knowing I had a learning challenge, I saw my soul—my life—as a cylinder of stainless steel, with no foot hold, no hand hold. And I kept trying to climb up to the sun, and I would slide down all the time.

JON:

Did you leave a little scrap of chocolate on it?

HENRY WINKLER:

There is no chocolate on it. I've licked it clean.

JON:

Your father spoke a ton of languages and you struggled academically. What did he think about how you turned out?

HENRY WINKLER:

When I was growing up, not knowing I had a learning challenge, I saw my soul—my life—as a cylinder of stainless steel, with no foot hold, no hand hold. And I kept trying to climb up to the sun, and I would slide down all the time. I needed my parents support when I was failing. I needed their support. I didn't need them to tell me I was stupid.

I eventually made it to the lip of this cylinder and pulled myself over and I'm working and having a great time. At first, my father and mother didn’t want me to go on television, but all of a sudden they became co-producers of my life, very involved but by that time, I didn't care anymore. I had needed them when I was confused and didn’t [get them]. So when they saw my success, it didn't touch me for one second.

There was a sense that I didn’t exist outside of their being my parents. They wanted me to be their image. So I made the decision that I would be a completely different parent. And that I would just listen to anything that the three children had to say.

JON:

But didn’t they have two strikes against them: one, growing up in the over-privileged part of Los Angeles, and two, their father is very famous. So why are your kids not fucked up?

HENRY WINKLER:

Because there was no show business in the house. And we were strict—there were rules in our house. When the kids wanted to go to a party, I would call the parents and say, “You're going to be home, right? Is there drinking?” If there was, they couldn't go. And what I found is that children always say, ‘Oh my God, you're the only person who ever calls, You're terrible!” But inside they're going, Thank God.

And what I found is that children always say, ‘Oh my God, you're the only person who ever calls, You're terrible!” But inside they're going, Thank God.

JON:

Same in our house. One time when our daughter was in, maybe, seventh grade, she went through the yearbook and said, “He smokes weed, she smokes weed, she smokes weed, he smokes weed.” She pointed to every other kid in the class except her. But she was secretly glad we gave her an excuse not to. Emily [my wife] had only three rules: No serious drugs, no tattoos, and no motorcycles.

HENRY WINKLER:

People literally tell me that they ride a motorcycle because the character inspired them, but I never rode a motorcycle in my life. I just acted like I knew what I was doing.

JON:

You faked it well. I’ve heard the Fonz was sort of some somebody that you could never be.

HENRY WINKLER:

No, he was somebody that I wanted to be. In high school I would call a girl in the middle of August and I would wear an overcoat because I was so nervous I shook.

JON:

Did the whole jumping the shark thing hurt you?

HENRY WINKLER

No. A guy named John Hein came up with it in his dorm room at the University of Michigan. It caught on. He went on to have a book, a board game, go on Howard Stern’s radio show. He built a career off of me. But we were number one for four or five years after the phrase, and every time they mentioned it, they put a picture of me on water skis. At that time, I really had great legs. So I didn't care for one moment.

JON:

You've always worked, but wasn't there a point, maybe 20 years ago, when you weren't exactly struggling but when you weren't getting the parts that you would have wanted?

HENRY WINKLER:

When Happy Days finished, ABC said if I brought then a show I liked and it appealed to them, they would put it straight on to television. They gave me an office and an assistant. And the first show that I brought to ABC (with my partner at the time) was “MacGyver.”

But as an actor I went from the mountaintop—55,000 letters a week— and slid right into the valley for the next eight, nine years. I started to produce because I couldn't get hired as an actor from 1983 all the way to 1991.

JON:

Wow! Would you go for auditions?

HENRY WINKLER:

My agent would put me out there and people would say, ‘You know, he's great, he's a wonderful guy, really good actor. Funny, So funny. But he was the Fonz.’

JON:

Did you ever feel that you were a has-been?

HENRY WINKLER:

No, but I felt very sad that I couldn't do what I dreamt of doing since I was a little boy. I felt very left out that I couldn't get an audition and I was very frustrated but I was never defeated.

When I did a TV movie, I was told, ‘We can't put you in the credits. Why? Because you were the Fonz and you will knock the balance of the movie out of alignment.’

But then they said, ‘During the test screenings, when you walked on screen you got applause.’ Oh, okay. And of course I did the press, and I just thought, What a great closing of the circle.

JON:

So how was your “Barry” audition?

HENRY WINKLER:

We were at an estate planning meeting on Ventura Boulevard in Los Angeles. There’s so much to think about. Recently I wrote a codicil to my will that I need to be buried in sneakers, because you don't know how far it is from the gate to your cloud, and with a $20 bill because there might be a concession stand.

Anyway, I get a call in the car, ‘Bill Hader wants to meet you for a new show on HBO.’ I said, ‘Oh my God, HBO!’ I've never worked for HBO before. This is a big deal. Bill Hader! I've watched him all these years on Saturday Night Live.’ I said, ‘Is Dustin Hoffman on this short list?’ If Dustin Hoffman is on the list, I'm not getting the part. But he didn’t try out.

Recently I wrote a codicil to my will that I need to be buried in sneakers, because you don't know how far it is from the gate to your cloud, and with a $20 bill because there might be a concession stand.

JON:

Can you say who else was up for the role of Gene?

HENRY WINKLER:

I never found out, but backstage at a John Lithgow play, he asked how I was doing. I said, ‘Better’ and that I had this part. He said, ‘Oh, you got it. I wanted that.’ Wow. Oh my God, that was the greatest thing. Wow, wow! I've seen him in everything on Broadway. And I've written him notes, his Churchill in “The Crown” was divine.

JON:

So what advice did your son Max [a director] give you before your audition?

HENRY WINKLER:

I’d made Bill laugh in an audition but then I'm waiting so long I figured I'm probably no longer in contention. I get a phone call, and Bill said ‘I just wrote two scenes last night— want to come in and play?’ I immediately emailed my son the scripts. He now directs me on the phone. I'm ad libbing and he said: ‘Respect the writer.’ And the rest is history. Wow!

JON:

You include Bill Hader on your list of geniuses.

HENRY WINKLER:

First of all, Bill Hader is a cinephile. He knows every piece of celluloid or tape ever created by man. He knows who's in it, who wrote it. He knows that he can quote it. The circle that is made with Bill Hader and Alec Berg—I’m telling you, if you ever get a chance to be associated with one or both, you run, don't walk. I'm a very lucky actor.

JON:

You’ve done Shakespeare, right?

HENRY WINKLER:

Not really. At Yale years ago, I did a special for CBS called Henry Winkler meets Shakespeare.

With my dyslexia, I can't read it but I learned through my ears so I know the difference between greatness and not.

I know this. 400 years ago or so, he wrote these plays, and people are doing them in every village and city on the earth.

JON:

We’re coming full circle.

HENRY WINKLER:

Shakespeare writes the human condition. His characters just happen to wear a sword. They happen to wear shoes with curls at the front. But in any one of those plays, you recognize someone in your family. You have characters you met in your work or have seen at a party. Every one of them.

JON:

Thanks, Henry.

After hearing Henry's list, I'd love to hear your ideas of who are the G.O.A.T. directors....

Watching Fonzie on Happy Days was appointment TV for me as a 10-year-old. I admire Henry Winkler even more as an adult. Finding out in recent years that he had a learning disability and how he overcame it gave me the inspiration to work with my son who had learning challenges of his own. When my son was still in elementary school, we would read the "Hank" books together. The stories were very relatable. I really enjoyed reading this article to see what Henry Winkler has been up to as of late.