Remembering Charlie Peters

The eccentric founder of The Washington Monthly changed journalism, government, the Democratic Party — and my life

I hope you will read all of the appreciations of Charlie Peters, who died on Thanksgiving Day, posted on the Washington Monthly site. Beyond these recollections about the magazine’s founder and animating spirit, and long obituaries in The New York Times, The Washington Post and Politico, there is still much more to say about Charlie’s impact on journalism, his critique of the performance of government and his significant influence on the moderate wing of the Democratic Party. But I’d like to tell a more personal story about my obsession with getting a job working for him. Here’s some of what I remember:

That summer, I was eager — even desperate — to meet the man, but it was not to be.

The year was 1978 and I was a ridiculously over-privileged (my wife prefers “under-deprived”) kid, then working as an intern in the speechwriting office of Jimmy Carter’s White House. I had shaken President Carter’s hand on the South Lawn and shaken President Ford’s hand in the East Room in 1975. Thanks to being a member of the lucky sperm club, I had also met Martin Luther King, Hubert Humphrey, Robert DeNiro and Robert Redford —and as an eight-year-old had seen the Beatles when they played in Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

While I was hardly blasé, none of these legends were central to my sense of who I was and wanted to be. But the idea of possibly meeting Charlie Peters, already a deity in my little world of aspiring political journalists — now that would be thrilling. The magazine Charlie had founded less than a decade earlier — The Washington Monthly — contained the smartest, freshest and often funniest writing about politics and government in the country, and I inhaled each issue in Harvard’s Lamont Library.

My boss that summer was Jim Fallows, a former Rhodes Scholar who had been named Carter’s chief speechwriter at age 27. Jim was a Charlie protege, as was another journalist I revered, Nick Lemann, who had been the top editor of The Harvard Crimson when I was a freshman. Nick, who was amid his tenure as an editor, suggested I come over to the Washington Monthly’s ramshackle offices around lunchtime and maybe I could meet Charlie. Maybe.

Charlie was around 50 then, and, as in so much else, decades ahead of his time in his decision to work almost exclusively from home, a tiny house on V St., NW — twice borrowed against to keep the magazine afloat — that he shared with his saintly wife, Beth, and their son, Chris.

Beth’s work at a school paid most of the bills and allowed Charlie to stay home all day reading books, clipping articles, scrawling his quirky, insightful column “Tilting at Windmills” (Don Quixote was a hero) in illegible longhand, and later, writing two fine works of history. (Five Days in Philadelphia and We Do Our Part.) But mostly, he thought. In a world of received wisdom, Charlie was a genuinely original thinker, with a mind that forged ores of common sense into a brilliant alloy of skepticism and idealism.

The only time Charlie ventured out of the house was to drive his aging Oldsmobile sedan downtown for a wine-soaked lunch, which he used as a way of charming everyone from obscure Pentagon whistleblowers to Katharine Graham, who became a good friend (in part because Charlie introduced her to Warren Buffett) — despite the fact that Charlie, fearless as always, routinely ripped the Washington Post in the Monthly.

Charlie would usually stop by the office for 10 or 15 minutes on the way to lunch to drop something off for his hyper-competent assistant, Carol Trueblood, without whom (and this applied to her successors, as well) the magazine would simply not have appeared each month.

Nick figured I might catch him this way, and I almost did. But at the moment I arrived, Charlie was already scurrying out, a smiling West Virginia butterball, maybe five-foot-six, with deep-set raccoon eyes (like mine!), and better things to do than talk to Nick’s friend.

When I moved to Washington after graduation, I caught a glimpse of Charlie on the street and he smiled again but — deep in thought — didn’t stop. I was not deterred. With a couple of New Republic pieces under my belt, I applied for a job at the magazine. No dice. I wrote a short article, which one of Charlie’s talented editors, Gregg Easterbrook, entirely re-wrote, and with good reason. No cigar. I wrote another, longer article that was published after more extreme editing and was finally granted an interview with the great man. To my horror, it lasted only four minutes and consisted mostly of Charlie asking me if I got along with my father, a question that perplexed me. I later learned that he believed anyone who didn’t would never get along with him and thus should not be hired. It turned out I gave the right answer, which also had the advantage of being true.

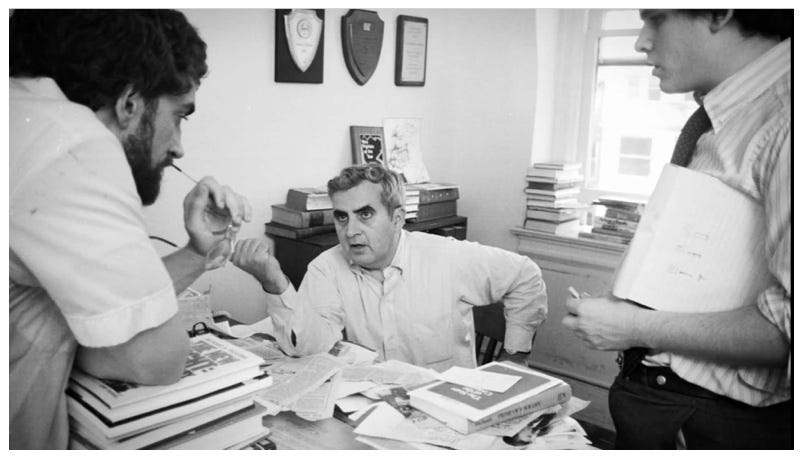

I was hired in 1981 for $8,700 a year with the understanding that like all of Charlie’s twenty-something editors (he employed only two or three at a time) I would put in 16-hour days doing everything from writing cover stories to taking out the garbage — then move on to a real job (in my case, at Newsweek).

Charlie’s intensity and (usually) endearing eccentricities lent a slightly comic touch to his epigrams and what we called “the gospel” — the coherent collection of ideas that undergirded the magazine. Phone calls with him lasted a minute and a half, tops, and always ended with him banging down the receiver without saying goodbye. “Rain dances”— when Charlie would jump up and down and tell you what was wrong with your article, you, the country and the world — lasted longer and, though he did no line editing, always led to a much better draft. I remember one day my friend Cliff Sloan was sitting in my office when I was called in for a rain dance. Cliff heard Charlie yelling at me down the hall and thought I had been fired. I shrugged. It was business as usual.

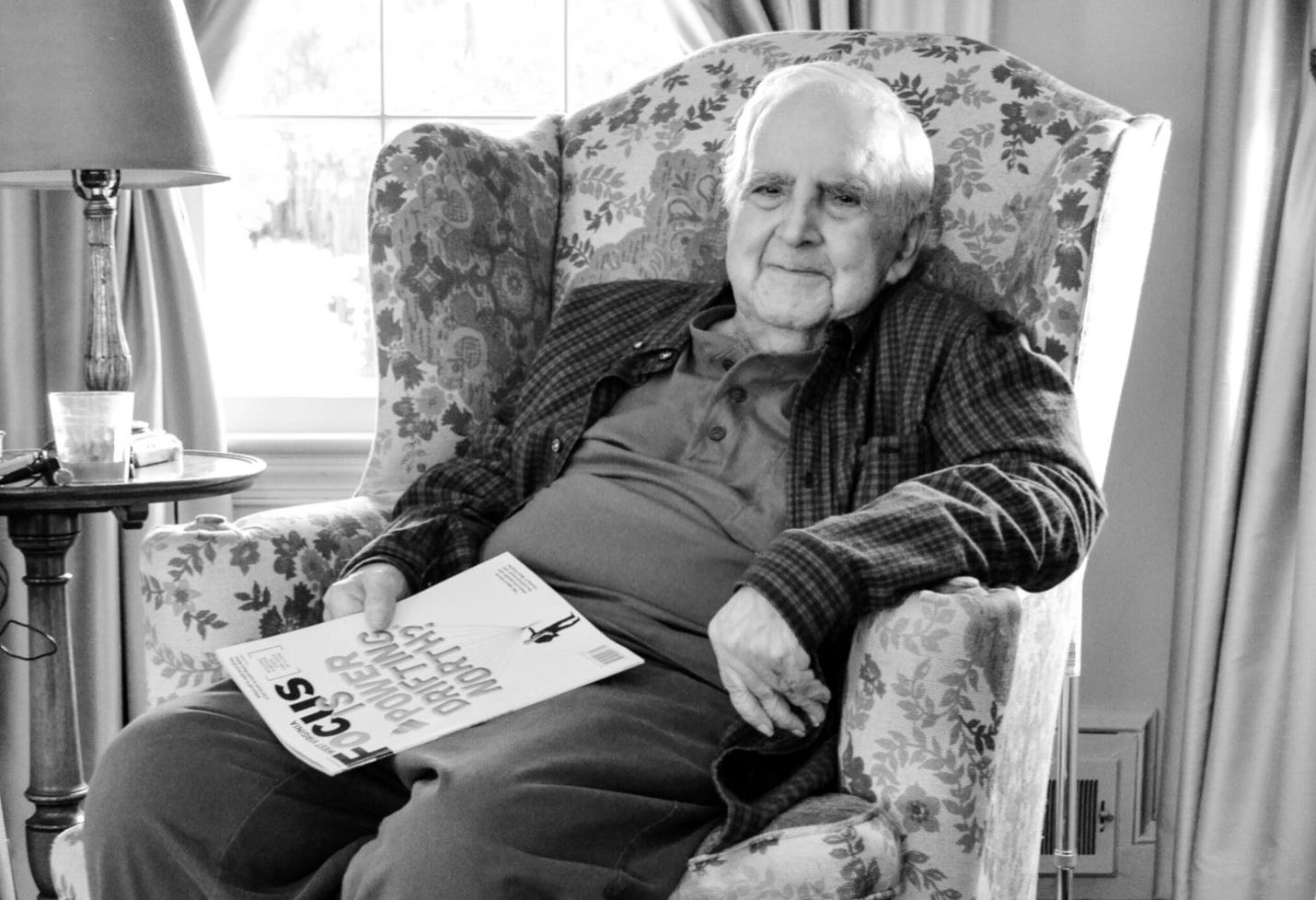

Rain dances were not conversations. Those would come later — after I had moved on — and were a source of great satisfaction to me over the decades. This was especially true of the last time we spoke, earlier this year, as he sat propped up in his basement, aided by an oxygen machine and the glow of an artificial Christmas tree that — his own person to the end — he kept lit all year long. We talked about his road trips with JFK in West Virginia in 1960, the Biden presidency and mutual friends but mostly just basked in our warm feelings for each other. I had loved a Beatle and, like others in our extended alumni family, had come to believe a Beatle loved me, and my life was the richer for it.

Thanks for writing, Sheila...It's a close call but I don't think Substack is a sewer, at least not yet. I won't quit when the hate posts are still "a tiny fraction" of what they do. At the same time, that was an important article by Jonathan Katz, a fine journalist whom I know and respect. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/11/substack-extremism-nazi-white-supremacy-newsletters/676156/ If he gets off Substack, I will have to take a harder look. I get the drawbacks of too much content moderation, but all of us have to up our game against hate.

This is so warm and funny, I'm going to keep it to read over and over. Thanks for writing it.

Shelley Mickle