I know, I know, you’re thinking this is my third post in a row with the flavor of an obituary. All I will say in my defense is that the full title of my newsletter is “Old Goats: Ruminating with Friends” and that old goats have a way of moving off to their eternal pasture a little more often than younger people do. It should be no surprise that after unfolding my print edition of The New York Times each morning, I read stories on the front page first, then turn immediately to the obituaries the way other readers go to sports.

In my experience, the deaths of friends — like well-chosen facts in a felicitous sentence — have an eerie way of coming in threes. And as it happens, all three of my recent subjects — Rosalynn Carter, Charlie Peters, and now Norman Lear — were people I knew and revered even though I’m not much for reverence. (I knew Henry Kissinger, too, but did not revere him).

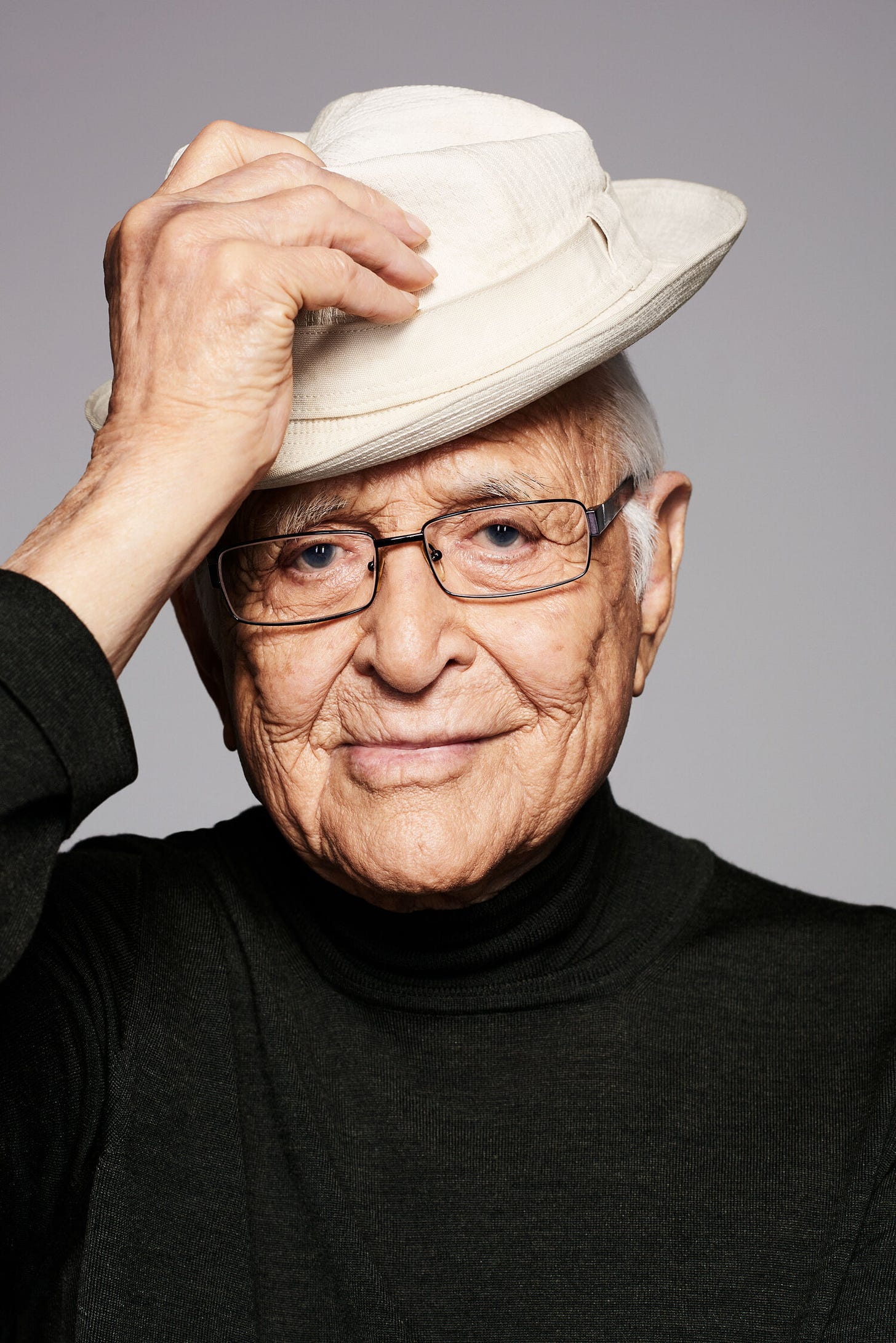

I didn’t know Norman Lear well, but I treasure our connection. Two years ago, after noticing that he was a subscriber, I tried to get Norman to sit for an Old Goats interview. He emailed me that he wanted to, but an assistant said he was “slammed” at the moment with an upcoming live show. A new TV gig at age 99! Even as he begged off, Norman wanted me to know that he had served during World War II under the legendary Colonel Frank Kurtz, whose amazing story his daughter, the actress Swoosie Kurtz, had recounted to me in an early Old Goats interview.

I leave it to the talented James Poniewozik to explain the immense cultural importance of Lear’s work. He rightly called him “a Great American,” and Dave Chappelle went even further in this 2017 Kennedy Center tribute, noting that for him and other latch-key kids, television became “a surrogate parent of sorts” and “Norman was the best parent I could have possibly had.” Chappelle concluded: “You taught me that the person on the other side of an argument from me is not my enemy — it’s a person that I love that I’m willing to convince, and you make me know everything’s gonna be alright if we can laugh together.” Now, that’s a unifying vision.

Beyond Norman’s achievements, we could all use a little of his spirit. Norman didn’t become successful until he was 50, which helped give him a wry decency that’s uncommon among Hollywood poohbahs. His son-in-law, Dr. Jon Lapook of CBS News, explained his philosophy of life — emblazoned on teeshirts at family reunions — as “Over and next,” with a sketch of a hammock in between. That roughly translates as stop fretting about the past; start living in the sweet hammock of the present, and always welcome the next adventure. Sometimes, he’d exult over living in the moment by kissing his wrist and saying, “I love my wrist!”

Norman was a hard-headed reformer. Three or four times in the 1990s, when I was a Newsweek columnist (and Newsweek meant something in the culture), he’d phone me and say he wanted to come to my office in New York to talk about one of his causes —usually People for the American Way, which he’d founded in 1980 to fight the Moral Majority and the evangelical right (a menace depicted brilliantly in Tim Alberta’s new book) but also the Business Enterprise Trust. The latter was a non-profit he co-founded to showcase successful businesses with a social conscience. Norman put on splashy award shows and produced case studies still used in 500 business schools. I remember him spreading out photos of ergonomic office chairs for my consideration, then telling me with a smile, “Every office should have these!” Whether I wrote about one of his projects or not, he decided I was someone he might want to spend a little time with, if for no other reason than to pursue what his family called his “engaged curiosity.”

So, a few times in the ‘90s, we went to fancy restaurants for lunch and shot the breeze with Norman in his trademark tennis hat. I wanted to quiz him, of course. I was impressed that at his peak in the late 1970s, 120 million Americans a week would watch his shows — a level of cultural dominance that was improbable then and impossible to imagine now. Norman would patiently answer a few questions, but it was obvious that he wanted to talk to me about politics, so we did. I was flattered that he was so interested in my views until I saw that he amiably queried almost everyone he met — determined to consume the full buffet of life.

Like my father, Norman was a Jewish World War II combat aviator who had become a strong liberal after the war despite being raised in a conservative home. He said his bigoted father was the model for Archie Bunker, while Edith Bunker was based on, of all people, Jesus Christ, which was why the episode when she briefly lost her faith struck such a chord.

With shows like Maude and The Jeffersons, Norman did as much as anyone to advance the identity of women and minorities — to see people who had never been truly seen on white-bread American television. But he also toyed with identity —tapping stereotypes and daring the audience not to get the joke. His shows were built on playing 22 minutes of micro-aggressions for laughs, an impossible theme in today’s world.

Even so, all of Norman’s shows had a beating liberal heart. Not long before he died, I saw an “All in the Family” episode where Archie talks a man out of jumping off a ledge. Fifty years on, it was still funny and moving. Another episode displays how far ahead of his time Archie was with guy-at-the-end-of-the-bar idiocies that his irredeemable Queens neighbor has now somehow turned into his platform — crude life imitating superb satire:

In 2016, Garry Trudeau and I — fresh off of Alpha House — were in LA to pitch Netflix on a new show (It didn’t fly, alas). Norman, then 96, and his wife Lyn invited us to their spectacular (but not over the top) house in the Hollywood Hills, which was full of amazing art and had the best view of LA or any other city I have ever seen. After a what-the-hell-am-i-doing-here dinner with a dozen celebrities (e.g., Jerry Seinfeld), we screened a new HBO documentary called, If You’re Not in the Obit, Eat Breakfast, an amusing look at people thriving in their nineties, including Norman, Carl Reiner, Tony Bennett, Stan Lee and Dick Van Dyke, who — energized by a wife who is 45 years younger — was gliding around the living room as if still sweeping chimneys in Mary Poppins.

Dick will celebrate his 98th birthday this week. Norman made it to 101. After the dinner party, I got a warm email from Norman that ended:

“Let’s keep this moment going.”

Thanks for this, Jonathan. Norman's creations became fixtures in my mother's house; mom was an Eisenhower Republican who, I think with Norman's help, made a slow transition to Democrat. And, somehow, Norman managed all this AFTER he turned 50! I must admit that sometimes I give in to negative thoughts about how "it's all over" at my age (the same as yours). Norman has given me hope! Over and next, indeed!

He was an amazing talent and you were so fortunate to be able to have this access and clearly a friendship as well.