How to Lead an Accidental Life

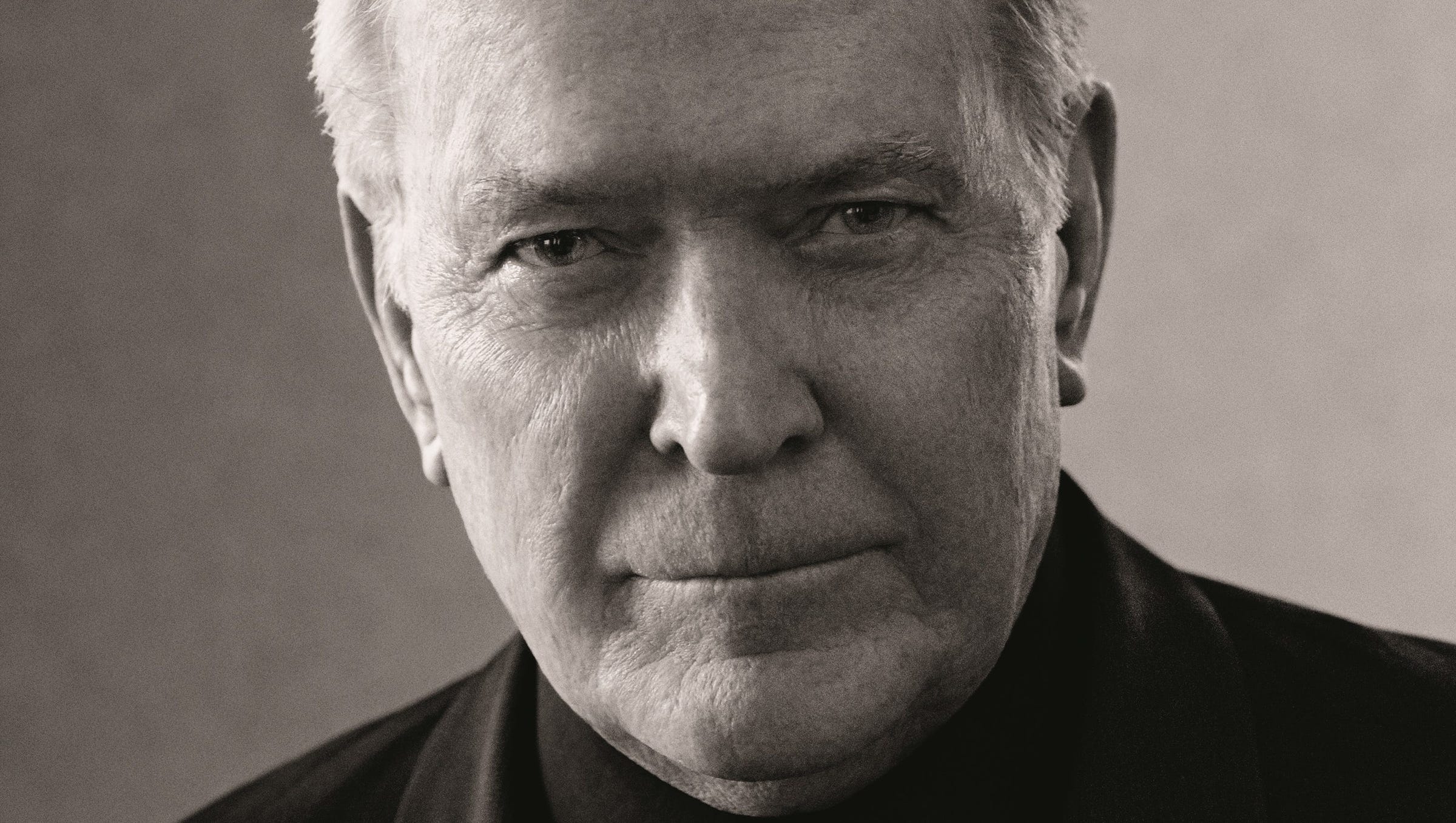

Terry McDonell, the legendary editor of Rolling Stone, Esquire and Sports Illustrated, on what his mother taught him.

Terry McDonell — the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame [2012], former editor-in-chief of Sports Illustrated, Esquire, and Outside magazines, among others — has a new, short book out: Irma: The Education of a Mother's Son that I consumed in one sitting. It’s about his mother, Irma, whom he conjures beautifully with spare, quirky, affecting prose. Terry rightly insists that if you want to buy “Irma” or any other book online, you do so through Bookshop, which along with LitHub, he helped found.

I met Terry in the early ‘80s at Newsweek, where he edited me and landed me in trouble with my wife Emily one night by getting me to go drinking at Runyons, a famous sports bar, until after dawn. He took his mother’s advice — “Don’t stop moving” — and offered his own to his sons Nick, a writer, and Thomas, an actor and director: “Your first responsibility is to make your life as interesting as you can.” Terry, who was raised in difficult circumstances in California after his father was killed during World War II (when Terry was an infant), has always had an uncanny sense for what’s next. We spoke about the state of magazine journalism in this country — and a lot else.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Is the 150-year era of great American magazine journalism over? Is that part of America's past now?

TERRY MCDONELL:

The journalism's not over, but the packaging will keep evolving. The intellectual mix between covers, the humor and all the wonderful ironies that you got from reading or just paging through a magazine will be gone with the physical object. I mean everything from the pacing of the stories and departments to the photos, illustration and layout to the headlines and display copy. Every issue of every magazine was unique. Going forward the best fashion and art magazines will hold on, and there'll be some one-shots and quarterlies, but traditional magazines of ideas on paper are over.

JON:

It's very sad to me, and it must be sad to you also.

TERRY MCDONELL:

I remember working for Sports Illustrated and being very, very proud to work there. And it meant a lot in the culture. Now, not so much. Many of these magazines have been undermined.

JON:

Before Irma, you wrote a book with great war stories about being a magazine editor and knowing all these great writers, The Accidental Life: An Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers. Why did you call it that?

TERRY MCDONELL:

There was an editor named Bob Sherrill who was famous for a lot of outrageous magazine-editor things. I worked for him in LA. I was a reporter, and he thought that I could be an editor, so he took me under his wing. He always said that you didn't want to go to the Los Angeles Times because then you’d wake up in 30 years and you'd still be at the Los Angeles Times, probably not running it. But if you chose to move around a lot and go serendipitously to wherever — to whatever accidental life — you'd have a far more interesting life.

JON:

One of many things that I liked about that book was the honesty about all the celebrities you've known and worked with. Let’s talk about one of Rolling Stone’s most famous writers, whom you knew well. Of the stories that you tell about Hunter S. Thompson, what is your favorite?

TERRY MCDONELL:

He’s in New York promoting something, and there's a party for him at the Abbey Tavern. I've got my sons with me; they're five and seven. And we're going up to say hello to Hunter early so it won't be too crazy, and Hunter’s at the top of the steep stairs, looming. Remember, he's 6’3”, maybe even taller, and he's a real presence. We climb up the stairs and when we get to the top, he squats down like a catcher, pulls out his Dunhill’s, opens a pack and says to my sons: “You guys want a smoke?”

JON:

I have one of my own. In 1994, you had given Hunter an assignment to do a profile of Jack Nicholson, who was spending a lot of time in Aspen at a house he owned with [record producer] Lou Adler. I told you that I was going skiing there and you asked me to try to obtain this article from Hunter, whom I knew only slightly. And I was thrilled. It made me feel like I could get a little taste of what it was like in the glory days. So I arranged to meet him at the Woody Creek Tavern. He showed up hours late, and when he got there he was pretty inebriated. I was with my brother and a couple of his friends. At the end of the evening this one guy hadn't said anything. Finally he piped up and he said, “Hunter, boxers or briefs?” This infuriated Hunter Thompson, and he had the bartender throw us out of the tavern. He didn't answer the question. Suddenly we're out in the snow on our asses.

At the time, in addition to working for Newsweek, I was a consultant to MTV, and they were doing these town halls with President Clinton. I told Tabitha Soren, who was the anchor, about this experience and when she was warming up the crowd of college kids for the rapid-fire round of questions they could ask the President, she said, “You know, you could ask him: ‘What’s your favorite ice cream?’ Or ‘Boxers or briefs?’” And one of the kids did it. And Clinton answered the question.

I never told Hunter that he was indirectly responsible for the most embarrassing question ever asked of a president.

TERRY MCDONELL:

Hunter could be very charming and was a lot of fun, but sometimes he was way off the rails.

JON:

What happened to him at the very end before the suicide?

TERRY MCDONELL:

He was in a lot of pain. He was addicted to alcohol and cocaine. And, in the end, that [road] goes right off a cliff.

JON:

You wrote in The Accidental Life about all the editors who over the years have jumped out of buildings.

TERRY MCDONELL:

[Laughs] Yeah, but not in a while.

JON:

What is it about our business? Is there something about being a writer or editor?

TERRY MCDONELL:

It’s a cliché that our business attracts unstable, compulsive people, who drink too much and gobble speed or whatever. There are also reporters who are very fat. They all say they thrive on deadlines, but I have always thought that pressure is a huge factor in their mental health.

JON:

On the flip side, there’s the fun. In Irma, you recall telling your sons: “Their first responsibility was to make their lives as interesting as they could.”

TERRY MCDONELL:

Don't you agree?

JON:

I do, but I never framed it that squarely to my kids. I did warn them about certain jobs in business or law that could be deadly, and that they should, in Diana Trilling’s words, lead “a life of significant contention.” They’re all great, but they don’t like to argue about serious stuff as much as I do.

TERRY MCDONELL:

My mother told me: Everybody should go their own way. So I told my sons that. They loved it whenever I would say, “this or that one goes his own way.” They say it about each other: “He goes his own way.” And it made them best friends as well as brothers, which was exactly what I wanted.

JON:

The Times ran a review of your book which I didn't like because it likened you to Hemingway — when you're actually very explicit in the book that you have big problems with Hemingway. Just because you write in a spare way doesn't mean that you're writing resembles Hemingway’s — you have your own voice.

TERRY MCDONELL:

That review was baffling. At one point the reviewer, Alexandra Jacobs, quotes me as wanting to “make literature in a manly way,” as if anyone would seriously write such a stupid thing. Within the context it was self-mocking: "He [McDonell writing about himself in the book in the third person] knew it was a pose but had not considered where he had picked it up or where it might lead.” That is what Irma is about. And as for Hemingway, he was drunk on himself and a terrible father. He started all three of his sons drinking before they were teenagers, and took Jack, the oldest, to a whorehouse when he was thirteen. He bullied and seethed and raged on, beating his chest until his boorish and nasty behavior reflected all the horrors of the manhood he had created not just for himself but for his sons until he put both barrels in his mouth and died in his bathrobe.

JON:

What got me interested, too, is that you’re working through your masculinity issues in a way that he didn’t. And, while your earlier book was mostly about men, this book is mostly about women. Did you evolve on some of these gender issues?

TERRY MCDONELL:

Irma had this evolving feminism that she grew into, as she became more powerful in her own life. Ultimately, being really pissed off that there was no chance to become Superintendent of Schools, where she worked.

When I first met Kay Graham [CEO of the Washington Post Company, which owned Newsweek], Kay would touch her earring, sometimes, or her necklace before she would say something. My mother did exactly that. When I told my mother that story, I said, “Also you wear your hair the same way.” She said, “That doesn't make any difference at all.” She would point out things like that. It was sometimes like, “I'm grown up,” but she's spanking me because I didn't quite understand. And it made me attracted to complicated women, the kind of women who bust you for showing off — not just for being a bad boyfriend, but for being an intellectual asshole or a jerk in one way or the other. When you stand up when a woman enters the room, you don’t do that for the woman alone, you're doing that for yourself, out of respect.

JON:

There are so many memoirs by men who have daddy issues, but there aren’t very many books about mothers and sons. In your case, you were raised by a single mother with a horrible stepfather. And you write about such a fascinating transitional generation — your mother’s generation, and my mother’s — trying to work their way into a more feminist perspective.

I was also lucky enough to know Kay Graham pretty well. You have a line about her in Irma that I thought was pitch perfect: “She could be imperious, and then drop ‘shithead’ into a description of a US senator.”

TERRY MCDONELL:

She really liked you.

JON:

Another thing you do that I'm not sure I've ever seen in a memoir is you confess to bitterness. The most common faux-sentiment in a memoir is, “Well, I'm not bitter.” You actually were bitter [about your stepfather] at a certain point, although you don’t really delve into it.

TERRY MCDONELL:

My stepfather if he were alive today would be unacceptable on absolutely every level. He was a sexist. He was a racist. He was a bully. He was violent. He was drunk. He was just running wild, and he was not alone. Growing up, you have two choices: You decide to become like them because that's what men are “supposed to do” — or if you have a strong mother, you see that is the wrong way, and you are learning from your mother how to be a good son and a good man.

JON:

This is so fascinating to me because, you know, we have this mythology about the Greatest Generation. It’s sugar-coated with their service in World War II. My father, who saw a lot of action in World War II, was an anomaly, because he didn't have these bad qualities that you just mentioned.

What I realized, reading Irma, is that she and my mom were taking part in the revolution of rising expectations. If she hadn’t seen her role as pushing back against those really ugly parts of the patriarchy, then our generation, those born after World War II, would be in even worse trouble. Thank God for the mothers who were challenging these really damaged men of the so-called Greatest Generation.

TERRY MCDONELL:

These women would get married and have a great two-week honeymoon and then, often, the husband would go off to war and God knows what kind of trauma— and then come home to a wife and child he didn’t really know.

JON:

But your mother eventually divorced him. The divorce rate spiked for these war brides. Some of them were still teenagers when they got married in the 1940s and early 1950s. And then, 10 years or 15 years later, they finally threw the bastard out.

TERRY MCDONELL:

My mother was married to this bad guy for 12 or 13 years. The day he left, I hit him over the head with a small kids work bench.

JON:

That reminds me of Bill Clinton going after his stepfather, Roger Clinton, which I discussed with him on more than one occasion. It's almost an American archetype of the stepson standing up for his mother against the violent stepfather. I wonder about those who couldn't do anything to protect their mothers, and what sort of damage that may have done to them over time.

“…the story of a stepson hating and resenting his stepfather is a classic story. What is ignored is the story within that of a strong mother who steps in and turns it all around for her son.”

TERRY MCDONELL:

It can spin into very, very dark places. But the story of a stepson hating and resenting his stepfather is a classic story. What is ignored is the story within that of a strong mother who steps in and turns it all around for her son.

JON:

Shifting gears: can you kind of conjure what life was like in the 60s and early 70s in California? With Joan Didion’s passing, and [the movie] Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, it’s taken on this rosy hue — this idea of “I'm nostalgic for something that I never experienced.” What was the ratio of really exciting to Charles Mansonish terror?

TERRY MCDONELL:

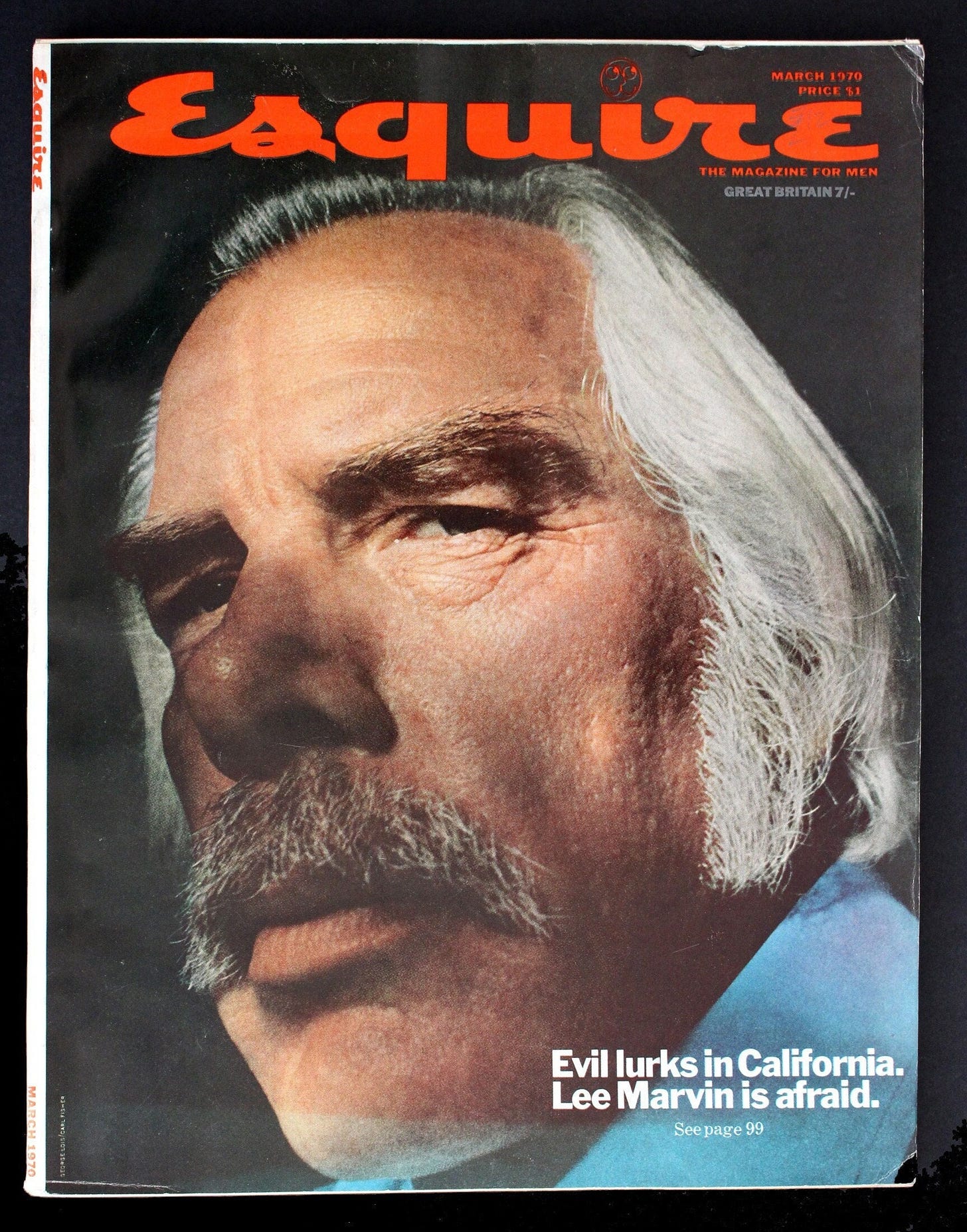

[There was an issue of Esquire that featured] Lee Marvin on the cover in some grotesque look. The cover line was, “Evil lurks in California. Lee Marvin is afraid.”

Don't forget, Joan Didion was disapproving of what went on in Haight-Ashbury. She was aghast that they were giving acid to a very young child; it made for a great story but she was aghast.

JON:

She was more conservative than people think.

TERRY MCDONELL:

Way more conservative.

JON:

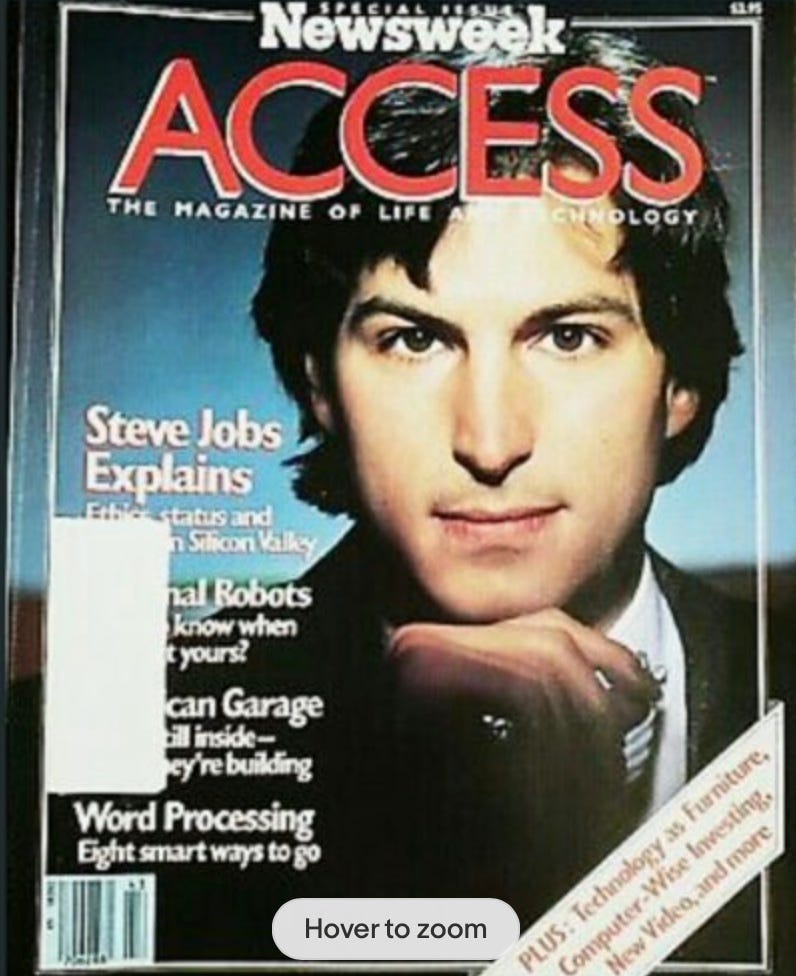

So the other thing that came out of California was tech, and you were there very early. When we first started working at Newsweek together when you were an assistant managing editor, you produced in 1984 something called Newsweek Access, which as far as I know was the first special issue published by the mainstream media entirely devoted to the tech revolution. There’s a line in Irma where you write [in the third person]: “He tossed references to HTML5 around like Frisbees, although he had never played frisbee in his life.” What was the ratio of prescience to bullshit in that period?

TERRY MCDONELL:

In the beginning, it was so exciting to be around those guys: Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, John Doerr. Jobs had a brilliant rap about what he was doing — that it was like “a bicycle for your mind.” He painted a very optimistic picture and I thought, wow, he is right.

JON:

I was too stupid and East Coast to get involved in the tech revolution. As you went on to a succession of high level-editing jobs at a bunch of different magazines, it had to have been a real advantage that you could toss HTML5 around like a Frisbee.

TERRY MCDONELL:

It was. I’m not bragging, I'm just saying it was really fun.

JON:

Do you think that if in the 90s we had gotten people used to paywalls, that there wouldn't have been the same collapse?

TERRY MCDONELL:

If we had built commerce into our browsers at the very beginning, and had the confidence to say, “This is valuable stuff — you have to pay for it,” it would have been a completely different story. Many more media companies would have gotten to the place where The New York Times now is.

JON:

The big crisis is in local news. If people had been conditioned to pay for local news online 25 or 30 years ago, we would be in a much better place. I was talking to the editor of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, who was telling me that in another city, one of the largest in Louisiana, the local leaders came to him and said, “We have nothing to hold our politicians and others accountable. We're turning into a feudal society here.” And this is happening in news deserts all over the country, where people can't make change or improve lives in their communities, because they don't have any local news organizations. There are interesting experiments — The Texas Tribune is doing really well — but all of us need to get in that fight.

TERRY MCDONELL:

Yeah. We really do.

JON:

You’ve written that corporate life is more like a spy movie than a cowboy movie. What did you mean by that?

TERRY MCDONELL:

I got that from John Huey [another legendary editor]: Cowboys shoot it out. Spies, on the other hand, work the back channels.

JON:

So to change metaphors, what was the secret to your success in the piranha tank of New York high-stakes media?

TERRY MCDONELL:

I got this from my mother, too: You don't have to talk loud to get people to hear you; you don't have to fight about everything to get things done. Move on — do not stop being in motion.

JON:

At one point in Irma, you write: “big fucking trouble — unfulfilled dreams.” What were your unfulfilled dreams?

TERRY MCDONELL:

I have no complaints.

JON:

But there was a period when you were less capable of counting your blessings. Is there anything that you could share with people who are struggling with getting older, asking, “How do I appreciate the life that I've led, and not focus on my anxieties or unfulfilled dreams?”

TERRY MCDONELL:

Everybody who steps away from a job where they felt that they could bring change begins to rethink everything. It can lead to depression and second-guessing. It’s a new kind of obstacle course. It affected me.

JON:

What are you working on now? Which of your various activities excites you most?

TERRY MCDONELL:

I'm trying to sell this book. I'm also involved in Decrypt, a website Josh Quittner founded in 2018 with a simple mission: to demystify the decentralized web. I'm involved in Book Shop. I’m not sure what the next step is going to be with Lithub but I’m thinking a lot about that.

JON:

Can you talk a little bit about Lithub?

TERRY MCDONELL:

Five years ago, Morgan Entrekin and I co-founded it as a kind of organizing principle in the service of literary culture; which to us meant a single, trusted, daily source for all the news, ideas and richness of contemporary literary life. Now it's the biggest, most important literary website in the world. That’s not hyperbole. It aggregates, but it also assigns its own stuff. And it’s top editors, Jonny Diamond and Emily Firetog, are brilliant. Then we spun off Crime Reads, which does the same thing for the best writing from the worlds of crime, mystery, and thrillers—a very robust literary culture.

JON:

How is Bookshop.org doing?

TERRY MCDONELL:

As you know, Bookshop works to connect readers with independent booksellers all over the world by providing a platform and tools to compete with monster Amazon. Andy Hunter, who was LitHub’s first publisher, is the brains behind it. Booksellers get a percentage of every sale and we’ve raised more than $25 million since 2020. Book Shop also supports their presence in local communities, which is crucial. It [Bookshop] was been especially useful to independents booksellers in England during Covid. It was like we were saving the world and the British press loved us. It’s been harder to get the word out here.

JON:

Well, that's too bad because people should know about it.

Thanks, Terry.

Jon, so surprised that you (unintentionally) instigated the boxers or briefs affair. Would it have been out of character for gonzo Hunter to laugh it off and say "panties"? What about Bill?

Thanks for shining a light on Terry's accidental journeys through journalism. I've also hopscotched through various endeavors in life, and thankfully I'm still moving and testing my powers.

In this conversation, though, there is much nostalgia to celebrate, and much to lament. In my youth, the small town near Pittsburgh had a daily newspaper delivered to our porch 5 days a week. In the late 1950s I checked the archives for the announcement of my birth; I even touched the physical paper sheet from 1949. On the main street, The Book Shop carried national magazines, newspapers, and paperback fiction and non-fiction; I always visited there on weekends to find the latest in print, like LIFE, LOOK, NEWSWEEK, TIME, MAD MAGAZINE, or "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich". Back then, reading the news was tactile, and thus seemed more personal. If indeed all politics is local, then perhaps there is a correlation between the death of the local news and the sickening demise of American political discourse.

Great interview. Thanks to you both. The paywall issue is so important. I think that the New York Times' refusal to charge for many years was a kind of a death knell. How could the Detroit Free Press or Pittsburgh Post Gazette construct a paywall if the NYT was free? My wife was a senior editor at the WSJ when News Corp took over. Murdoch was determined to make it free until he looked at the numbers. I wish the NYT had joined the WSJ in charging form the start.

Just bought Accidental Life and looking forward to digging in.