A Trump Coup Trial Primer

Everything you need to know ahead of the most monumental test for the rule of law in American history.

This piece was originally published in Washington Monthly, co-authored with Cliff Sloan.

Until now, the highest-level criminal trial in American history was the case of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was acquitted of treason in 1807.

But the Burr trial — and all of the tabloid-fodder murder trials of the last two centuries — shrink into insignificance next to United States of America v. Donald J. Trump, the weightiest criminal case brought against the former president, the first (barring unforeseen circumstances) to be tried, and the most monumental test for the rule of law and the U.S. Constitution since, well, ever.

With the trial scheduled to begin on March 4 in Judge Tanya Chutkan’s no-nonsense courtroom (though appeals will likely delay it some), let’s set the table for what to expect from a world-historic moment of democratic accountability — in a case that, if the judge has her way, will unfold shortly before the most pivotal presidential election for the future of the country since Abraham Lincoln squared off against George B. McClellan in 1864.

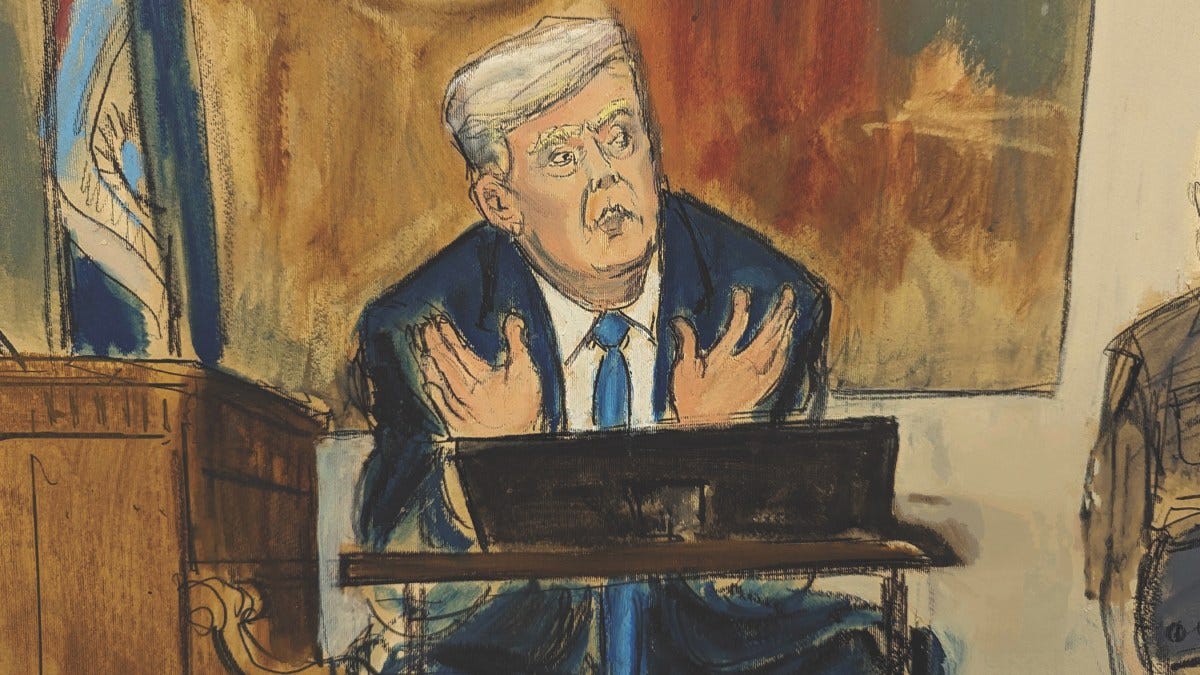

For all of its significance, the case may not be sensational; many of the details will be familiar to those who paid close attention to the January 6 Committee hearings in the House. But the battle between Special Counsel Jack Smith and Donald Trump’s lead defense attorney, John Lauro, could prove epic, even if it isn’t on TV.

Smith, appointed by Attorney General Merrick Garland to investigate Trump, is a hard-charging career prosecutor who spent five years probing politicians as head of the Public Integrity Section of the Justice Department. He was best known for successfully prosecuting former Virginia Governor Robert McDonnell (though McDonnell’s conviction on corruption charges was overturned). After leaving the Justice Department, Smith joined the Hague as chief prosecutor, litigating war crimes in Kosovo.

Lauro is a resourceful white-collar criminal defense attorney with extensive experience in fraud cases. Beyond Georgetown Law School, he’s a proud graduate of the Gerry Spence Trial Lawyers College — yes, there is such a place — where the institution built by Spence, a flamboyant criminal defense attorney, taught Lauro what the school calls “a deeper understanding of human behavior and the mastery of universal storytelling.”

Before the storytelling on both sides begins, the rest of us should decide on the title of the case. Think the Scopes Trial or the Trial of the Chicago Seven or the O. J. Simpson Trial. At first glance, U.S. v. Trump is appropriate, but it turns out the Mar-a-Lago documents case is often shortened to United States v. Donald J. Trump (the full name is United States v. Donald J. Trump, Waltine Nauta, and Carlos De Oliveira). Lauro calls the D.C. proceedings the “J6 case,” but that’s too narrow, given that the former president’s criminal attempt to overturn the results of a fair election began months before January 6, 2021. Other obvious names seem inadequate. The Trump Federal Conspiracy Trial (to distinguish it from the conspiracy case in Georgia) and the Federal Election Interference Trial are cumbersome.

So let’s call it what it is — the Trump Coup Trial. It’s the best chance we have as a nation to bring Trump to justice for the worst of his many sins: masterminding a deeply unpatriotic plot to defraud the public and thwart the peaceful transfer of power. Trump was indicted on four counts, but they all involve the same sinister act: an attempted coup d’état.

It’s easy to get confused by the seven Trump cases working their way through the courts. The former president has already lost in civil suits involving sexual abuse and defamation (the E. Jean Carroll case) and long-term business fraud (the Trump Organization case), and he faces a civil suit filed by injured Capitol Police officers and House Democrats alleging incitement on January 6. Together these cases — if upheld on appeal — have the potential to cost Trump hundreds of millions of dollars in liquidation losses, disgorgement, and damages.

On the criminal front, the former president faces a total of 91 serious charges, alleging that he engaged in a number of nefarious plots, including the following: directing a wide-ranging conspiracy aimed at stealing the presidential election in Georgia (where convictions would be out of reach of his pardon power as president); falsifying business records in paying off a mistress — Stormy Daniels — in New York (where convictions also would be out of reach of a presidential pardon); and willfully refusing to hand back nuclear and other military secrets he kept unsecured at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida after he left office. In the latter case, prosecutors seem to have Trump dead to rights, though the complexities of reviewing national security documents and the rulings of U.S. District Court Judge Aileen Cannon will most likely delay the Florida trial until after the 2024 election.

This leaves the Trump Coup Trial as the most historic — even if, like the classified documents case, it is subject to a newly reelected President Trump corruptly ordering the Justice Department to drop the whole thing. To streamline the case and increase the odds of its being tried before the election, Smith asked the grand jury to indict only Trump, leaving Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman, Jeffrey Clark, Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro, and at least one other as unindicted co-conspirators for now.

In the months since the federal indictment, Smith’s prosecution has been bolstered by Chesebro, Powell, Jenna Ellis, and, possibly, Mark Meadows flipping in the Georgia case. While it’s too early for the government to disclose its witness list, expect all of them to be on it. Meadows, in particular, could be a devastating witness against Trump.

Trump’s strategy, of course, is to defy Judge Chutkan’s preference for a speedy trial and run out the clock. So Lauro and his team are busy raising every imaginable objection. As a practical matter, almost all appeals on these issues will — under the rules of federal criminal procedure — be heard only after the trial is over. There are three exceptions: Chutkan’s gag order, which would not delay the trial even if it were overturned on appeal; Trump’s double jeopardy claim, based on his acquittal in the 2021 impeachment trial (which borders on frivolous and can be quickly rejected); and — most important — Trump’s immunity claim, which also lacks merit but could give the Supreme Court a chance to gum up the works.

The gag order is fully justified. Trump’s attacks on court employees in the civil case involving his business — which puts their lives at risk — have already led New York Judge Arthur Engoron to impose modest fines. It wasn’t long before Chutkan’s patience wore thin, too. On October 29, she reimposed a gag order that she had temporarily suspended, singling out an appalling social media post directed at Mark Meadows, Trump’s former chief of staff, that said any cooperation with prosecutors is what “weaklings” and “cowards” do. The gag order was not in effect when Trump wrote the post, but, as Chutkan noted, the language would “almost certainly” have violated it.

Chutkan wants to avoid jailing Trump for contempt; her order is mild compared to what any other defendant of comparable recklessness would receive. It allows Trump to attack Joe Biden and the Justice Department, and even the judge herself — just not the lawyers, witnesses, and court personnel connected to the case. Trump — being Trump — will likely at least tiptoe up to the line and perhaps cross it, using social media to taunt and endanger people all the way through jury selection, the trial, the verdict, and beyond.

Doing so helps advance his narrative that he’s the victim of vicious, unfair attacks for merely expressing his free speech rights about the election. In spewing his usual insults, Trump’s legal and political arguments are in perfect alignment. The problem for him is that there’s nothing in that strategy to help him delay the trial.

The D.C. Circuit already has clarified and upheld almost all of the gag order, adding leeway for Trump to criticize Jack Smith. Trump’s further appeals on this issue will not affect the trial date.

Lauro’s best bet for delay is his flimsy claim that Trump is immune from prosecution for virtually anything he did as president. His appeal is based on a 1982 Supreme Court decision in Nixon v. Fitzgerald, a whistleblower case in which the high court granted presidents broad immunity from civil suits. Trump’s lawyers argue in their motion that such immunity should be extended to criminal cases because the Constitution says that impeachment and conviction is the only way to hold the president of the United States accountable for breaking the law.

This is a lame argument. Nowhere does the Constitution say that presidents can only be held criminally accountable by Congress. In fact, when Trump faced impeachment in 2021, his lawyers argued that he should not be impeached because he would be subject to criminal prosecution after leaving office. In explaining on the Senate floor why he voted against conviction, then-Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell essentially recommended such prosecution as the proper remedy. Trump’s lawyers are echoing the argument that Richard Nixon made after resigning his office in disgrace: “Well when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” There is no evidence that the Founders believed this.

On December 1, Chutkan issued a stinging opinion rejecting Trump’s immunity claim in language that invoked the first principles of constitutional government. For a president to have immunity from all criminal prosecution would be to endow him with “the divine right of kings,” which is what the American Revolution was fought over. Chutkan also knocked down his flimsy double jeopardy claim. Trump’s lawyers immediately appealed to the D.C. Circuit, hoping to slow the case until after the election. But then, in a surprise move, Jack Smith — arguing that this is a “case of paramount public importance” — asked the Supreme Court to take the case directly, as it has in several cases in recent years.

On December 22, the Supreme Court declined to do so without dissent. Anticipating this possible outcome, the D.C. Circuit had already put the immunity appeal on a fast track, with arguments scheduled for January 9. If, as expected, a three-judge panel made up of two Biden appointees (Judge Florence Pan and Judge Michelle Childs) and one George H.W. Bush appointee (Judge Karen Henderson) quickly upholds Judge Chutkan on the immunity question, Trump will almost certainly appeal for an en banc ruling, meaning a review by all 11 judges.

As part of the chess game, Jack Smith would likely again ask the Supreme Court to review the case immediately. If the Court again denies this request — taking more time off the clock — then Trump’s en banc request will be considered by all 11 judges. They are likely — given their records — to agree with the three-judge panel on rejecting Trump’s immunity claim and thus that there is no need for taking the unusual step of reviewing it en banc. But if even one Trump-supporting judge takes a while to write a dissent, which is quite possible, that could slow the process, delaying Supreme Court review and the opening of the trial. It’s impossible to know at this point whether that delay would be weeks or months.

When the immunity case gets to the high court, Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson would almost certainly side with the prosecution. Clarence Thomas (who should, but likely wouldn’t, recuse himself because of his wife’s role in the efforts to overturn the election), Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch might well side with the defense, although Gorsuch voted against Trump in the 2020 subpoena cases. So the immunity question would likely be resolved by which side won over two of the three remaining justices — John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, all of whom have occasionally ruled against Trump.

If we assume that the Trump Coup Trial will proceed, the prosecution will tell the jury a story similar to the one outlined by the January 6 Committee, whose historic work prodded the Justice Department to bring charges. It’s the story of a president who told elaborate lies claiming that fraud caused his loss at the polls — lies that helped him orchestrate a corrupt conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 election and remain in power. He did so “knowingly” — a word used 36 times in the indictment — and thus with clear criminal intent by rejecting the consistent conclusion offered by a parade of Trump lawyers and other advisers who will testify that they told him he had been fairly defeated. In the prosecution’s theory of the case, Trump obstructed the federal government’s legitimate function in collecting, counting, and certifying the ballots and deprived voters of their right to have their votes count.

If the prosecutors’ case proceeds along the chronological lines of the indictment, we’ll hear early on from witnesses such as Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and former Speaker of the Arizona House Rusty Bowers about how Trump and his coconspirators used false claims of election fraud to try to convince them to take legitimate votes away from Biden. Expect testimony from former Attorney General William Barr, former Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe, former Director of Cybersecurity Christopher Krebs, and several others about how Trump was repeatedly told that he lost and that his claims about fraud were false and belied by the evidence — and how he immediately and “knowingly” went out hours later and lied again about winning.

The defense will argue that Trump truly believed he had won. But what basis can he claim for such a “belief”? The prosecution will explain to the jury that you can’t say, “I robbed the bank because I genuinely believed the bank had money I was entitled to.”

When former Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen, likely a key prosecution witness, told Trump that the Justice Department would not attest that the election was stolen, Trump replied, “Just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican congressmen.” Those of us credentialed to cover the trial will be looking at the jurors to see how they absorb that one.

The most damaging moment for Trump may come when prosecutors get to the slates of “fake electors” assembled in seven states. They will introduce evidence that Trump consciously helped plan how to trick supporters into signing fraudulent documents, and then phoned the chair of the Republican National Committee, Ronna McDaniel, to ensure that the plan was in motion.

Trump’s lawyers will claim that he was just following the precedent of Hawaii in 1960, when Nixon won in an early count (by fewer than 150 votes) and John F. Kennedy’s campaign submitted a slate of electors that was accepted in the Electoral College. But the differences between 1960 and 2020 are glaring. To name just two: An official recount in Hawaii was underway when the Kennedy forces submitted their electors, which was not true in 2020; more significantly, JFK’s Hawaii slate was not part of a multipronged, multistate effort explicitly intended to prevent the congressional certification of the election and the transfer of power.

The prosecution will argue that Trump tried to convince the Justice Department to use deceit to force state officials to replace legitimate electors, and that he attempted to have Justice officials make knowingly false claims of election fraud to officials in the targeted states through a formal letter.

And, of course, the jury will hear how the president tried to browbeat his vice president, Mike Pence, into certifying his fraudulent electors before expressing no concern on January 6 that Pence might be hanged by the mob that Trump had assembled. The former president’s outlandish support for the insurrectionists — before, during, and after January 6 — will also likely be admissible.

The Supreme Court has agreed to hear a different January 6 case about the scope of the law on obstruction of official proceedings, which is one of the counts in the indictment. But, for at least two reasons, whatever the Court decides, it will not get Trump off the hook. The narrow construction of the statute urged by the defendant would make it apply only to evidence-related obstruction — but that is exactly what Trump is charged with in the phony elector scheme. And, in any event, two of the four charges against Trump do not depend on that law. Still, count on Trump to use that pending Supreme Court case to argue for delay (and for dismissal if he wins on this point).

So far, the case for the defense remains a big mystery. In his pretrial motions and public statements, Lauro echoes Trump and insists that the case should never have been brought, especially during an election cycle. Expect to see him (and possibly Trump himself) sounding these themes on the courthouse steps, which will give him a PR advantage over Smith, who won’t prosecute his case in public.

Lauro has bragged that one of his trademark moves is to keep his cases simple by not putting on a defense at all — just a strong opening statement, withering cross-examination of government witnesses, and a closing argument that the prosecution has not met its burden of proof. On the other hand, Lauro said last summer that he would call Pence if the prosecution did not; he believes the former vice president will testify that Trump may have insulted him but did nothing illegal. Outside experts think this is wishful thinking and that, based on his leaked deposition, Pence’s testimony will seriously harm Trump.

Will Trump himself testify? While Lauro has noted that in general he hates putting his clients on the stand, he may have no choice if the case is going badly. And, of course, his client might simply choose to testify. Donald Trump rarely shies away from an opportunity to stage a spectacle featuring a performance by Donald Trump. In his only appearance on the stand so far, in the Trump Organization civil suit, he failed to impress the judge (there was no jury) with his rants, and chickened out of testifying a second time. We’ll see if a jury in another liberal city will be more receptive to his charms.

Whether he will be examining his own witnesses or cross-examining witnesses for the government, Lauro’s defense comes down to three narratives: The former president had no criminal intent or consciousness of guilt; he was merely following advice of counsel; and he was merely exercising his First Amendment rights.

None of these hold water. The weakness of Trump’s “no criminal intent” argument will be that a bevy of former senior campaign advisers and White House aides will testify that they told Trump he had lost, which will go a long way toward establishing that he knew he had done so. Moreover, his claims about alleged incidents of election fraud were clearly refuted by all available evidence and by more than 60 judges. The advice-of-counsel argument is undermined by the fact that Trump thought Sidney Powell was “crazy” and by testimony that Rudy Giuliani was peddling (bogus) theories, not advising his client based on evidence. Finally, there are a host of precedents establishing that corrupt acts are not protected by the First Amendment, sinking his “criminalization of free speech” defense.

All of this bodes well for Jack Smith’s case, but the bottom line is that he has to bat a thousand with the jury. While a D.C. jury is expected to favor the prosecution, it takes just one holdout to hand Trump a huge victory.

If he is convicted, expect a tough sentence. Chutkan has thrown the book at defendants in other January 6 cases, often commenting during sentencing about the seriousness of the insurrection. And in this case, Chutkan has already ruled that the president possesses neither a “get-out-of-jail-free” card nor “the divine right of kings.” Trump would appeal any conviction, of course, and he wouldn’t exhaust those appeals for years. In the meantime, buckle up for the constitutional ride of a lifetime.

Well documented legal case against Trump. To the point! Time will tell whether Trump goes to prison or gets away with his crimes. It is amazing how Trump is handled as opposed to ‘Everyman’ who might be in the same or similar situation. Trump is treated ‘special’ even though he is No Different from anyone else in the USA.

The congressional branch failed in dealing with Trump. Now it’s up to the courts. Unfortunately, the justice system moves slowly. The country must now wait patiently as the recipients of McConnell’s bargain.