There’s been a lot of talk lately about whether President Biden might withdraw from the presidential campaign. Barring illness, it’s now highly unlikely that he will do so, but it would not be unprecedented. Fifty-six years ago, on March 31, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson shocked the world by announcing that he would not seek reelection. At the time, one of his closest associates was a young man named Tom Johnson (no relation). After serving in the White House and then helping LBJ in the four years of his post-presidency, Johnson went into journalism, first as publisher of The Los Angeles Times in the 1980s (where we met when I was Newsweek’s media critic) and then as president of CNN in the 1990s. We talked mainly about LBJ, one of U.S. history's most productive and compelling presidents.

JONATHAN ALTER:

You were awfully young for your important job in the White House — only 24 years old. How did that happen?

TOM JOHNSON:

After I graduated from Harvard Business School, I applied for the White House Fellowships; it was the first year of the program. And somehow, someway, the selection committee, which was headed by David Rockefeller, chose me as one of the 15.

JON:

Were you there with Doris Kearns Goodwin?

TOM JOHNSON:

Doris came in the second year. She and I overlapped considerably, including both in the White House and the years following the White House, as she also worked on LBJ’s [memoirs], The Vantage Point.

JON:

We’ll get to the post-presidency in a little bit. What was your first year in the White House?

TOM JOHNSON:

It was 1965. I’d been a young reporter in Macon, Georgia. Bill [Moyers, LBJ’s press secretary] saw an uncommon background and chose me to work with him. He introduced me to LBJ on my first day. I'll never forget LBJ said, “Tom, we have not had any experience with this program before. So we just want to treat you like a full-time staff member.” And he did.

JON:

One of the reasons that I wanted to talk to you is that, like many journalists and historians, I've tried on a few different occasions to get Bill Moyers to break his long silence. Bill won’t talk about his time in the White House to Robert Caro or anyone else. If he did, what do you think he would say that maybe we don't know or that would put a new set of perspectives into our understanding of Lyndon Johnson? Let's start out in the 1965-66 period.

TOM JOHNSON:

I have urged Bill to do interviews. I served as one of Bill’s assistants for the whole year of ‘66. When Bill left to become publisher of Newsday, my title became Deputy Press Secretary under George Christian. Bill and I have remained very close friends. I urged him to write his own book. And I have been unsuccessful in persuading him to do it.

JON:

Something happened in ‘66 and early ‘67 between Johnson and Moyers.

TOM JOHNSON:

Bill’s brother Jim had died, leaving Bill responsible for his whole family. I happen to know that Bill was making $30,000 in the White House, the maximum being paid to special assistants, and that Bill was offered $100,000 to go to Newsday. LBJ thought that Bill was leaving him at a time when he needed him most. By then, the war was becoming very controversial. We were beginning to have riots and student protests. Bill had been the nearly indispensable domestic policymaker within the White House. He chaired the task forces that set up the Great Society in many ways. So, my speculation is that President Johnson felt Bill was somehow being disloyal to him. In my opinion, Bill had also begun to question the strategies and the policies of the Vietnam War. I never felt Bill was being disloyal. He served LBJ uncommonly well for so many years.

JON:

I wrote my senior thesis at Harvard on Vietnam policymaking in the 1963–64 period after the coup against Diem, when we went from a counterinsurgency commitment to a full-on conventional military commitment. One of my remaining puzzles about the whole thing is why Johnson didn't understand that 500,000 troops was just a bad idea. I mean, Douglas MacArthur understood it. How could Lyndon Johnson not understand?

TOM JOHNSON:

He said he was trapped between the doves and the hawks — a negotiated path of “get out now” and a continuing military campaign. LBJ was anguished over Vietnam almost every day. He so wanted to bring about peace during his time in office. But he felt the hawks would destroy him if he went the dove route. And I think it’s too bad. He had members of Congress and a few Generals in the Pentagon, such as General Curtis LeMay. LeMay wanted to bomb Hanoi back to the Stone Age.

JON:

Your notes, which were not part of the Pentagon Papers, are available at the LBJ Library, right?

TOM JOHNSON:

Most of my papers have finally been declassified by the CIA, the Pentagon, and the National Archives, with a few exceptions. By the time he finishes the final volume of his masterwork on LBJ, Robert Caro will likely have gone through my notes page by page.

JON:

Speaking of Robert Caro — I know you were interviewed by him. What was the most memorable thing that you told Bob?

TOM JOHNSON:

That LBJ, to his core, wanted to do whatever he could to bring about peace in Vietnam. He searched from every angle, sent every potential secret emissary we could send, including Henry Kissinger working through the French in Paris, sent a letter to Ho Chi Minh, and offered a billion dollars to reconstruct the Mekong Delta. I don't think anybody has captured how almost every waking hour of LBJ’s time that wasn't spent on something that was breaking news was: How can I get peace? I sat beside LBJ in so many meetings. I flew with him on Air Force One and Marine One. He’s pleading for ways to get out of there. And I think that's not been captured by many journalists and historians.

JON:

When did these anguished efforts take place?

TOM JOHNSON:

‘66, ‘67, ‘68, ‘69.

JON:

If Bob Caro looks at the Walt Rostow papers, your notes, and the other material that [LBJ aide] Harry Middleton deposited in the library, he will have some headlines. Is that a fair assumption?

TOM JOHNSON:

It has to be speculation because there are still documents that have not been declassified. I have pushed and pushed to get everything declassified because, frankly, I would like to use them in my own book.

JON:

You were there for lots of the conversations in 1968 when LBJ learned that the Nixon campaign had sent an Asian-American powerbroker and ardent anti-Communist named Anna Chennault to meet with the South Vietnamese and tell them they’d get a better peace deal if they waited until after the 1968 election. Johnson was appalled by this, but if he went public in an effort to help Hubert Humphrey [his VP, who was the Democratic nominee that year], the world would learn he had been spying on the Nixon campaign. What would the headline from your book be? Or would it be mostly new details of Anna Chenault’s operation?

TOM JOHNSON:

It would be details — the names of those [whose communications] were being intercepted. There was always speculation about the role of Spiro Agnew. There was always speculation about whether there had been some tap on the campaign plane that Nixon was using.

JON:

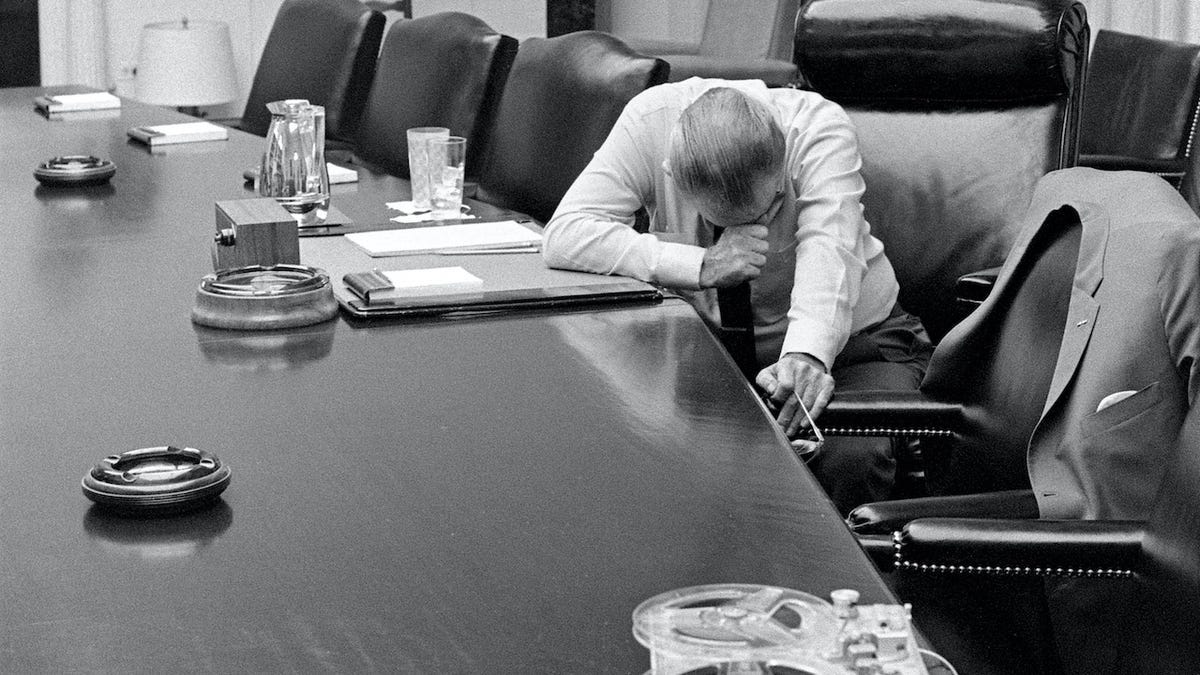

So let's change gears. There's that famous image of LBJ in the Cabinet Room with his head in his hands. And that's when he's hearing something about his son-in-law in Vietnam, I believe. What were the moments of greatest anguish that you witnessed?

TOM JOHNSON:

That was LBJ in the Cabinet Room, listening to a tape of then-Marine Captain Charles Robb, [Lynda Bird’s husband]. Keep in mind LBJ had both of his sons-in-law in the combat zone. Pat Nugent [Luci’s then-husband] was out there as a low-ranking airman, but he was often aboard US Air Force cargo planes flying wounded soldiers from the field hospitals back to Saigon.

JON:

Was there anything that LBJ said that reflected his anguish in a similar way that you remember that has not been reported?

TOM JOHNSON:

“I’m trapped.” That’s what he often said. “I’m trapped. I’m damned if I do, and I’m damned if I don’t.”

JON:

Do you think that's why he didn't run again? I know that nobody in the White House knew until he delivered the speech. I assume that you didn't, either. I once wrote a paper on that speech and learned he had a draft of the withdrawal language in his pocket all week. Lady Bird may have been the only one who knew, right?

TOM JOHNSON:

He had already had a major heart attack in the Senate; he was urged not to run by Texas Governor John Connolly [a close friend] through very private discussions that they had. LBJ said that he should not spend an hour, a day, a minute on political campaigning, if he could spend that time bringing about peace in Southeast Asia.

JON:

Did you suspect in late ‘67 or early ‘68, before the [March 12] New Hampshire primary, that he might not run?

TOM JOHNSON:

[Press Secretary] George Christian rushed into [my office] on the afternoon of the State of the Union [January 17, 1968] and said, “Tom, I can't trust anybody else to type this.” This was the document that LBJ placed in his inside jacket pocket that would announce that he would not seek a second term. So all I know is that I typed the document, which was not that different [from his withdrawal statement on March 31, 1968.

JON:

That would have been more than two months before he actually withdrew in that televised address from the Oval Office. So he was thinking about it before the State of the Union and the New Hampshire primary. I never knew that.

TOM JOHNSON:

It was a big secret ‘til the end.

JON:

So, to move forward just four days: Describe the day that Martin Luther King was killed.

TOM JOHNSON:

I was standing by the two wire service tickers in the press room when bells began ringing loudly. We knew a short ring was a bulletin, but a continuous ring was a flash. I looked at it coming across the UPI ticker that read “Dr. Martin Luther King has been shot”. I ripped it off and ran towards the Oval Office. I told Juanita Roberts [LBJ’s longtime personal secretary], “I must go in.” I handed the flash to LBJ. He just slumped back into his seat. Sitting to his right was Robert Woodruff, the chairman of Coca-Cola. To his left was former Georgia Governor Carl Sanders. And LBJ read it. He started picking up the phone; I think his first call was to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. One of the calls went out to Mrs. King, another to the mayor of Atlanta, And by then all the staff started gathering in the Oval Office.

JON: Did you ever meet King when he came in to see LBJ?

TOM JOHNSON:

No.

JON:

That makes sense because, by the time you arrived, they weren’t getting along very well. Jonathan Eig does a nice job on that in his new biography of MLK. In 1966, when I was eight-years-old, I met King in Chicago, as readers of OLD GOATS know; he came to my house for a fundraising event my parents held. By that point, [Chicago Mayor] Daley and Johnson were in pretty close communication on how to handle King. Do you remember anything about that?

TOM JOHNSON:

As the notetaker, I’m afraid that I had something called tunnel vision. I was so committed to getting those notes down and accurate and then getting my hand-written notes typed by White House Secretary Connie Gerrard. I do know that the relationship between Dr. King and President Johnson was badly fractured after Dr. King came out in opposition to the Vietnam War. Dr. King saw that far too many blacks were dying on the battlefield compared to the number of whites.

JON:

Did LBJ understand that his great legacy in civil rights was being badly tarnished because of the war?

TOM JOHNSON:

Yes. There’s no question the toll the Vietnam War took on him personally, particularly when you would see the monthly reports about the number of pilots who had not made it back and the body count. I always thought the body count was one of the most terrible things ever done. It almost showed that we were winning the war. It would say we have lost only 300 Americans, and the Vietnamese lost 1,000.

JON:

Did LBJ ever pull you into the bathroom when he was using it?

TOM JOHNSON:

He never stopped working. I've never known such a workaholic. He was not overseeing that family business out of Texas. He was a 24-hour politician. He watched the news and only the news on TV. He was on the phone when he was sitting on the commode. This was a working politician, a working leader.

JON:

That’s why it’s so hard to understand why he gave it up. There was a rumor that went through the ’68 Democratic Convention that LBJ was going to come to Chicago, change his mind, and be nominated.

TOM JOHNSON:

We had a 707 on standby. He had a couple of people in Chicago. He was watching all day. It was so speculative, but it was a rampant rumor going everywhere.

JON:

Did he want to be drafted? In other words, if he had heard from Chicago, “You know what? The delegates don't really want Hubert; they want the real thing. We could get a draft going like Roosevelt in 1940, and you could just come in and accept the nomination.” Did he want that?

TOM JOHNSON:

That is pure speculation. But I also felt it. I mean, Hubert Humphrey accepted the nomination. We were watching it in the bedroom at the ranch. I remember exactly who was in the bedroom: Mrs. Johnson, Luci, Jim Jones [LBJ’s last chief of staff], [Legal Counsel] Larry Temple and myself.

JON:

But what was he thinking? Did he want it?

TOM JOHNSON:

The word several people used was — he wanted the approbation; he wanted the applause, for people to have said, “What a wonderful president you were, how much you did with civil rights and voting rights.” I think he would have really loved that.

JON:

What do you remember about his last day in office? It must have been so hard for him on January 20, 1969, to actually say goodbye.

TOM JOHNSON:

I was asked to prepare a briefcase with the most highly classified documents concerning all covert actions that were underway around the world. He wanted Nixon to know everything. He wanted Nixon to know every secret. But he said something like, “I never had to push the button.” And then to me he said, “Here’s what I want us to do now. I want to finish my book. I want to complete the construction of the LBJ Library and the LBJ School of Public Affairs and finish the series of interviews with Walter Cronkite of CBS.” He wanted those projects to be completed before he died. He always believed that he would die young. And he did. He died four years later.

JON:

I recently watched the last Cronkite interview with him shortly before his death. He seemed like he was in a very reflective mood.

TOM JOHNSON:

I'll never forget an interview where he still had suspicions about the possible involvement of Cuba in the JFK assassination.

JON:

So he thought it might be Cuba, not the Mafia connection. How about you?

TOM JOHNSON:

I flew to Havana and met with Fidel Castro. He told me he had absolutely nothing to do with the Kennedy assassination. I’ll never forget his exact words, “Had we been involved in any way, you [the United States] would have incinerated my little country.” I’d never heard the word incinerated as a verb.

JON:

Well, I don't believe Castro. I'm with LBJ. I did the first print interview anywhere [in Newsweek] with Robert McNamara about the Vietnam War after his book came out in 1995—the first time he answered questions about Vietnam in 28 years. Later, we talked at length about the Cuban Missile Crisis. And Castro was ready to launch on warning in 1962, even though his little island would have been incinerated. My guess is that if he were willing to start a nuclear war in 1962, he would have been willing to be involved in killing the president of the family that had tried to have him killed.

TOM JOHNSON:

Jonathan, every source I have, every contact that I’ve built over the years, convinced me that the Russians never gave the Cubans independent control over the nuclear missiles that had been placed there by the Russians.

JON:

Right. But Castro wrote Nikita Khrushchev saying his people were willing to get incinerated. And they were willing to have nukes launched from their territory.

TOM JOHNSON:

If there's one topic that I have researched for years… I know that the Russians say they never gave Fidel independent control over the missiles.

JON:

To be clear, I’m not saying they did, only that Castro was willing to do it. Let’s go a decade ahead to when LBJ dies. You tell the story of how you called Walter Cronkite when he was on the air. Did he put you on the air?

TOM JOHNSON:

Mrs. Johnson called me and said, “Tom, we did not make it this time; Lyndon is dead. Will you handle the announcement and the arrangements?” I first called the Associated Press and UPI, and then the three networks. Of the calls that I placed, CBS took it right away. Walter Cronkite recognized my voice because of the work we did together on the LBJ interviews. Cronkite went directly from the commercial break into live coverage. It was the first time CBS had ever interrupted a show with live coverage on the air. But Cronkite interviewed me, and that's where the story broke. There had been several reports that LBJ had died in the months leading up to his death. His health was not good. He was eating nitroglycerin tablets like they were candy.

JON:

I'm in a similar position right now with Jimmy Carter, where I’m called with every rumor.

To go in a different direction: What’s your take on Ted Turner?

TOM JOHNSON:

Until I met Ted Turner, I thought LBJ was the most complicated man I had ever known. When I reported directly to Ted, I asked him, “Ted, what do you want from the new president of CNN?” He said, and I quote, “I want you to help me make it the best news network on the planet.” I asked, “What else?” And he said, “That's it, pal.” He’s called me pal for most of my life.

JON:

You were present when Gorbachev signed the dissolution of the Soviet Union?

TOM JOHNSON:

So he’s about to make this announcement. He’s sitting at his desk and reaches for a green pen that had been placed next to the documents. One of them was his resignation. The second would dissolve the old Soviet Union and convey the power of Russia to Boris Yeltsin. Gorbachev’s pen does not work. He looks over at his press secretary who does not have a pen. I reach in my coat pocket and hand him mine. But, he asked me, “Tom, is it American?” I said, “No, Mr. President I think it’s either German or Dutch.” He said, “In that case, I will use it.” CNN then broadcast live to all of the people of Russia and to the rest of the world this historic event. He then used my Mont Blanc pen to sign the documents. I had the audacity to ask for my pen back because it had been an anniversary gift from my wife Edwina.

JON:

Do you still have the pen, or is it in the Smithsonian?

TOM JOHNSON:

It was on display at the Newseum [now closed], displayed beautifully right alongside a piece of the Berlin Wall.

JON:

Where is all that stuff now?

TOM JOHNSON:

A lot of it is in storage. I had so hoped that somebody would step up and buy the Newseum, perhaps Jeff Bezos who had bought the Washington Post. But nobody did.

JON:

So, what do you think of CNN today?

TOM JOHNSON:

It is now, in my opinion, really back on track. I think they've hired a splendid new leader [Mark Thompson], who was a chief executive officer of The New York Times and before that, the CEO of the BBC. He is a very high-quality guy. He is a newsman, but more than that, he is into the new [digital] world in a major way. He has transformed The New York Times, and he's going to transform CNN.

JON:

So, I want to spend the last few minutes talking about a personal issue. I understand that you've suffered from depression intermittently over the years, and I'm wondering if you could revisit that, as painful as it is.

TOM JOHNSON:

I was hit very hard by depression after the more conservative members of the Chandler family removed me as publisher of the LA Times. My wife says I'd been battling it before that. I was examined at UCLA, and they said I have chronic depression; at that point, I started on a path of antidepressants with lithium, which didn't work. Fortunately, when I came to Atlanta as head of CNN, I met a new psychiatrist who said, “What you've been taking is not right for you,” and he put me on a new medication and talk therapy. I am a strong advocate of antidepressants; I want people to know that there are medications today that can enable you to get better. I think we need to combine it with talk therapy. I worked with Mike Wallace and Art Buchwald, both of whom had been hospitalized with their depression.

[My message is:] Do not kill yourself, for God’s sake — there are ways that you can get better! But first of all, you need a very good diagnosis by a trained professional, and second, you must be willing to try sometimes through trial and error. So much that goes on in our body chemistry is unknown, and so much is situational, but today, you can be treated successfully for depression. I spend a lot of my time trying to help people who have mental health issues, especially depression. The only way to eliminate the stigma is by talking openly about it.

JON:

Do you think that Lyndon Johnson had any undiagnosed bipolar illness?

TOM JOHNSON:

He had down days. But I never saw LBJ in a long period of depression. Looking back, it's amazing that he didn't, with all that was hitting him as he dealt with Vietnam, with attacks that he was getting from Bobby [Kennedy] and so many others. 1968 was one of the most astoundingly bad years of the American century or of American history.

JON:

I know you agree when I say I hope 2024 isn’t even worse.

Thanks, Tom.

Jonathan , this is an interview filled with insightful information on an era of history that is still open for discussion and knowledge. Thank you

Who’d have thought after such a resounding victory in 1964 that things would turn like it did!!! Oh boy, the 60’s and 70’s were interesting to say the least! Somehow we lived through them, I think!