The Death of the New Jersey Machine

It took a while, but the bossism of my Chicago youth and current home is finally done

The old politics in America died last week and no one noticed. I’m not talking about the old aristocratic Republican Party, or the old spirit of compromise in Washington, or the plain old fun that handicapping and refereeing the game provided me and my friends for decades, though those are now all dead, too. I’m talking about the city and county bosses who controlled politics in many cities from the late 19th Century until March 28, 2024, in New Jersey, when the last remaining machine finally conked out.

The old political organizations — from Tammany Hall in New York to the Pendergast Machine in Kansas City — offered ethnic groups a bargain: a city or county job in exchange for political work and contributions. Bosses (originally Irish but later Italian and Black) frequently provided good constituent services—and winning candidates at all levels—but they were often out-of-touch, undemocratic, and corrupt.

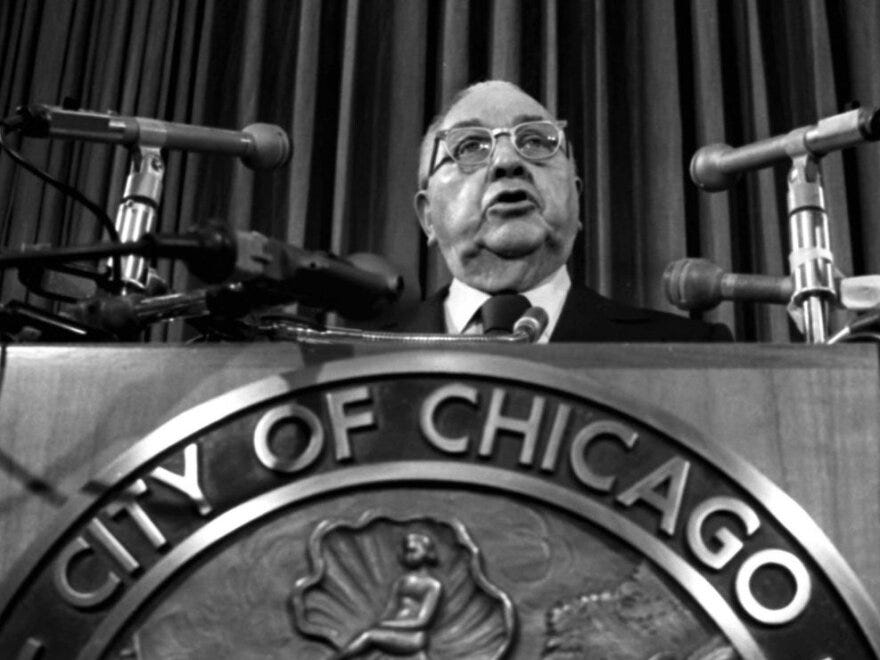

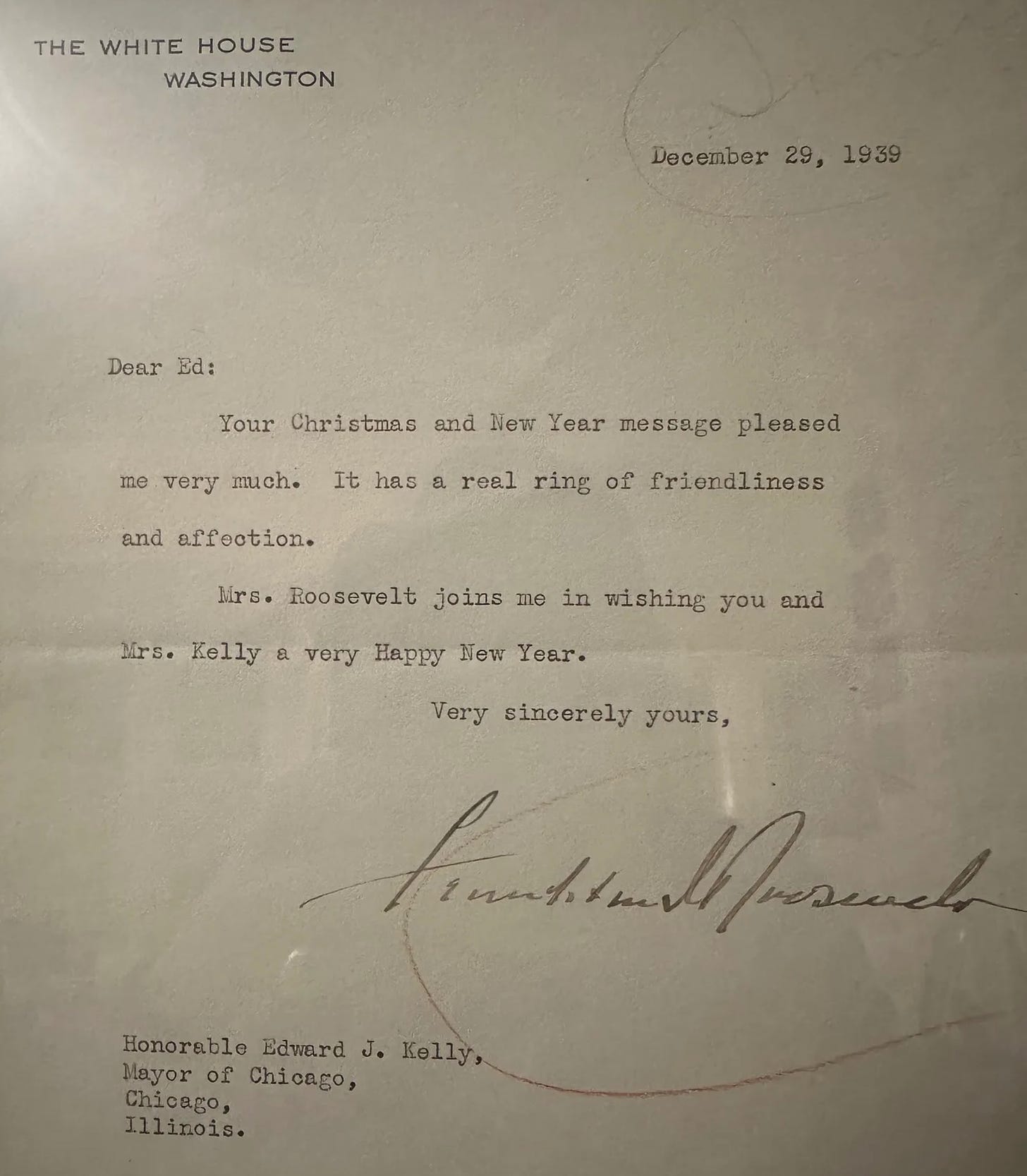

I was born in Chicago, the city most associated with machine politics. The old patronage system reached its pinnacle at the 1940 Democratic Convention with “The Voice From the Sewer,” perhaps the classic example of how bossism can occasionally lead to great things. That year, FDR claimed he didn’t want a third term in a letter read aloud by the party chairman to the delegates. But that was a ruse. At the direction of pro-FDR Mayor Ed Kelly, a party functionary in charge of Chicago sewers commandeered the sound system and began chanting “We Want Roosevelt!” from beneath the Chicago Stadium. The chant grew and soon FDR was drafted for an unprecedented third term, which meant that the Kelly-Nash Machine played an important part in saving democracy and winning World War II.

Here’s a warm letter from FDR to Kelly six months earlier. It’s one of my prized possessions:

In 1955, Kelly’s weak replacement was succeeded by Richard J. Daley, whose 21-year reign came to define machine politics. The Daley Machine — which extended in reduced form into the terms of Daley’s son — contained plenty of hacks and boodlers, but it also strengthened downtown Chicago and worked well for many middle-class families. It gave a job in the water department to Fraser Robinson, Michelle Obama’s father, who repaid the favor by working as a Democratic precinct captain on the South Side.

I grew up on the North Side, and my late mother, Joanne Alter, became the first woman Democrat elected in Cook County (in 1972). She had a fraught relationship with the Daley Machine, sometimes running with its support and sometimes not. As a kid, I viewed myself as a budding reformer. Every Election Day from when I was in sixth grade, my parents let me out of school to work a precinct for the independent anti-Machine candidates challenging the choices of what was then called the Cook County Democratic Central Committee, an unintentional echo of the power centers in Communist China and the Soviet Union. I would ring doorbells and hand out literature near a polling place. But I was no match for the “regular” Democrats — often city workers who weren’t going to let some privileged kid turn out the vote better than they did.

Sometimes, they had help. In 1974, when I was 16, I volunteered on the campaign of an independent Democratic candidate for Illinois state senate named Steve Klein. One night, I was climbing lampposts on Broadway (Chicago has a street by that name, too) to affix Klein posters. A squad car came over, and the officer looked up and asked me who I was working for. When I answered “Steve Klein,” he asked if he was a “regular” Democrat. I said no. “Get down and sit in the back of the car,” he said.

I was under arrest (sort of) for violating the 11 pm curfew that had been imposed in the wake of the disastrous 1968 Democratic Convention, the epic event, not incidentally, that ended the era of the smoke-filled room and led to today’s system of primaries determining the presidential nominee. The cops took me home and did so again when they caught me doing the same thing the next night. Two years later, Jane Byrne, a future mayor and my mother’s arch-rival, used my “record” to fashion a lie that Joanne Alter’s son had been arrested for ripping down Daley posters. The story of me looking like an anti-Machine vandal was on the front page of the old Chicago Daily News.

Around the same time, an obscure civic reformer named Michael Shakman was slowly destroying the Daley Machine. He filed a lawsuit that led to “Shakman Decrees” of 1972, 1979, and 1983 that crippled the patronage system by preventing city workers from being fired if they refused to do political work on the side, as Michelle’s father and thousands of others had done for many decades.

That left New Jersey—where I’ve now lived for 30 years— as the only remaining state with a major American political machine. The Garden State exists in a time-warp where a restricted kind of patronage survives, and county bosses handpick the candidates as if they’re little reincarnations of Frank Hague, the legendary (and suspiciously wealthy) boss of Jersey City until the late 1940s.

Now, finally, the bosses in the state of the real “Boss” (Bruce, of course) are on the run. On March 29, a New Jersey court invalidated the “county line,” a long-standing arrangement whereby county bosses win favorable ballot positions for the Democratic candidates they endorse while anti-machine candidates are exiled to “ballot Siberia”— basically out of the voters' sight line. Out of sight is out of mind: Once lumped with the fringe candidates, it has been extremely difficult for primary challengers to win.

The lawsuit challenging the county line was brought by Rep. Andy Kim, whose opponent, Tammy Murphy (wife of Governor Phil Murphy), was the candidate of the county bosses in the race to succeed disgraced Sen. Robert Menendez. Several bosses endorsed her despite her lack of experience just to stay on good terms with the governor. With this court decision (which will likely be upheld on appeal), Kim is now almost certainly headed to the U.S. Senate. I met him for coffee last month and came away thinking he will be an impressive new senator and national figure.

Over the last six months, Kim has built a terrific statewide grassroots organization, thanks in part to the help of progressives mobilized in the wake of Trump’s 2016 victory. Kim and these progressives will now be appropriately credited with killing bossism in the Garden State.

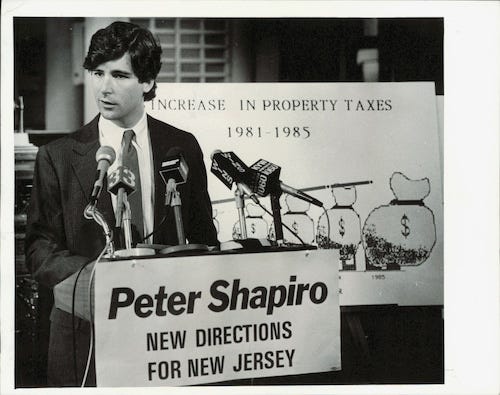

But they had help from a former wunderkind politician. In a beautifully appropriate coincidence, on the day of the court decision a friend of mine named Peter Shapiro died after a long illness. This was a personal loss for me; Peter and I were texting about Trump’s meme stock late Thursday night (He accurately predicted that DJT would tumble), and he died a few hours later. I was at his house the previous Sunday when word came that Murphy had withdrawn from the race, the first real sign that the old system was — like Peter — about to die.

In 1978, when Peter was 23 years old, he got himself elected the youngest member of the N.J. State Assembly. In Trenton, he won reforms in several areas, including the reorganization of county government. This dealt a significant (though not fatal) blow to bossism and corruption in New Jersey, and several articles appeared suggesting that Shapiro might one day become the first Jewish president. Peter was soon elected as the first county executive of Essex County, the state’s largest county (containing Newark). He lost for governor in 1985 and left politics for Wall Street, where he became a fantastically successful investor.

We need more people like Shapiro and Kim who will shake up the system and energize a new generation of political activists. I’ll miss Peter, and so will New Jersey.

I grew up in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood, where I was politically active from a young age with experiences that in many ways mirrored Jon Alter's. I was also honored and privileged to have served as Administrative Aide to his mother, the late Joanne Alter, who so capably represented taxpayers in her elective capacity by insisting on responsive and responsible government, even when it imposed peril to her own political viability. Jon's eloquent review of bossism generally, and Chicago's specifically, brings back so many memories. What a wonderful recitation of the way Chicago politics used to be. Bravo, Jon, and thank you!

So sorry for your loss. And for the loss to the public generally of people like Peter Shapiro! Of course they're successful in business--and just think what they could have done/could be doing in government. I'm glad to have learned about Peter today, and the Chicago Machine stuff is of course golden. That letter! I know it must be framed and hanging in a place of honor. I would be tempted to build it a shrine.