Ruminating with VINT CERF

The co-founder of the Internet warns that your grandchildren might not be able to see any photos of you.

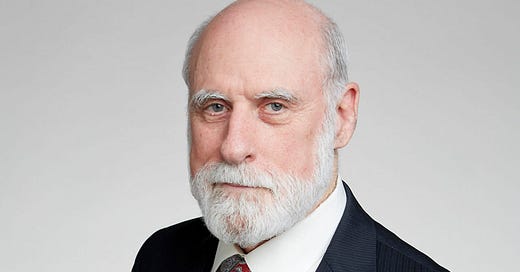

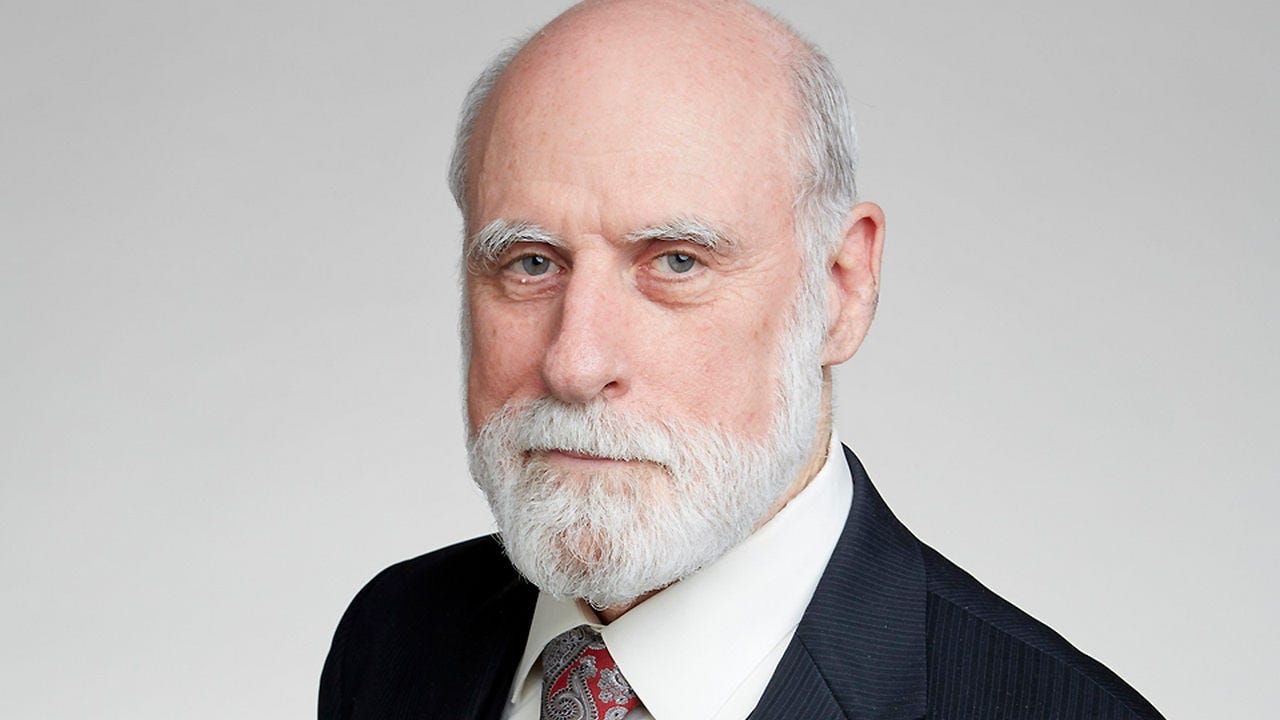

I met Vint Cerf through my wife, Emily, who booked him in 2014 on “The Colbert Report.” Born in California and trained at Stanford, Cerf and his colleague, Robert Kahn, played the key roles at Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in developing the Internet and Internet-related technologies that made the advent of the World Wide Web possible. In 2005, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and joined Google, where he serves as VP and Chief Internet Evangelist.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Hi, Vint. Thank you for for doing this. I'm a historian and I am deeply concerned about what you call “bit rot” and how within a few decades all of our digital records will have degraded and our history will be something out of the poem Ozymandias by Percy Shelley.

VINT CERF:

Look on my works ye Mighty and despair!

JON:

You gave a TEDx talk about what you call “the digital dark ages” but could you briefly lay out the problem and the need for what you call “digital vellum”? (Vellum is fine parchment made from calfskin that lasts for millennia).

VINT CERF:

The problem breaks out in several different dimensions. One of them is very physical. We have a variety of digital storage devices we invented over the years. There’s the five-and-a quarter inch floppy and the three-and-a-half inch floppy. There’s the disk drives, the CDs, the DVDs, external disks, memory sticks. The problem is that none of it lasts forever, certainly not as long as vellum does. And eventually, the machines that can interact with those devices stop working, or they're in the Smithsonian. So if you don't copy digital content from one medium to another, it may just disappear—either because bits go away, which can happen, or, like magnetic tape, eventually they deteriorate, or there isn't any hardware available that can read the stuff because it's been superseded by some new product which isn't backward compatible.

The problem is that none of it lasts forever…eventually, the machines that can interact with those devices stop working…so if you don't copy digital content from one medium to another, it may just disappear

There’s a second problem, which is that not all the software that's needed in order to correctly interpret the bits will be running 100 years from now. And there are only a couple of solutions to that problem. One of them is to copy—not for purposes of changing the physical medium but for purposes of changing the format, so that there's software that can still understand it.

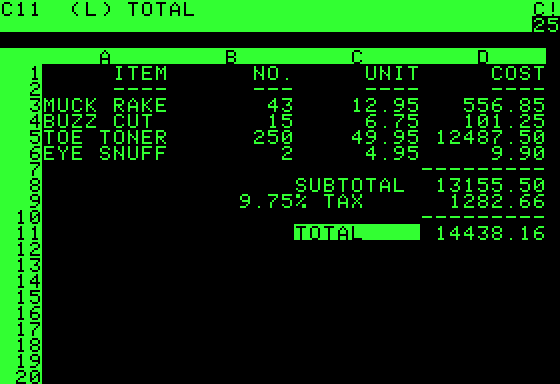

Another possibility is you actually emulate the hardware of the computers running the software. Remember VisiCalc? So imagine for a moment that you have a VisiCalc file that you really wanted to retain access to over a long period of time. You might need to either emulate the old Apple II hardware in order to run the old VisiCalc program, or find a piece of software that knows how to ingest this accounting file and write it out as Microsoft Excel. A researcher at Carnegie Mellon did emulation of hardware that could run old operating systems.

But the problem remains. A lot of people are now beginning to realize that all the photographs that they're taking on their mobile phones are going to have to be put somewhere else. There are cloud services like Google Photos where you can store all your photos and sort them in pretty albums and print them out.

JON:

But will enough be saved? Historians are very dependent on letters. In my Jimmy Carter book, I publish for the first time the love letters that he sent Rosalynn Carter from the Navy. Fifty years from now, how are people going to be confident that they can get the emails that they need to see?

VINT CERF:

They can’t be and that's the big problem. You're right—there’s a cost associated with this….

(Here Vint seems to be thinking of a new idea).

You could imagine...Here’s a crazy idea—not totally crazy. You know how we have life insurance? Imagine that we had data insurance.

JON:

Good idea!

VINT CERF:

You set aside a certain amount every year, and that money goes into the cost of keeping and maintaining digital archives— maybe copying them into new media and [also] copying them into new formats. A practice of preservation. The answer is, you have to figure out how to pay for it because otherwise it will go away.

“Here’s a crazy idea—not totally crazy. You know how we have life insurance? Imagine that we had data insurance.”

JON:

At a minimum, everyone should print out their best pictures on high-quality, non-acidic paper.

VINT CERF:

When people come to me and say, “What about my photos?” my answer is that it’s really important to print them out. Paper isn't as good as vellum but it's still better than bits that you're unsure about or for which the infrastructure may not be available.

We're having discussions with librarians and archives around the world. We get together and look for barriers to preservation—like copyright, which can turn out to be a big issue. Are you allowed to make a copy or a physical copy?

There’s a company in the UK called emortal that is trying to make a business out of preservation for people who are concerned about their digital information—not just photos of course but important documents like marriage licenses, deeds, mortgages, and family histories.

When people come to me and say, “What about my photos?” my answer is that it’s really important to print them out.

JON:

There’s a nice poetic quality in the return to paper. In the same way that backup paper ballots are now an essential part of preserving democracy, maybe paper might be a big part of the solution here in preserving our sense of family and who we really are.

VINT CERF:

It may be. However, let me remind you that the digital world is about more than static stuff. The spreadsheet, for example, can be printed out, but it's an instance of the spreadsheet; it's not the formulas and everything [beneath it]. The formulas are part of a complex data structure that needs interpretation by software. So we have an increasing amount of stuff that's digital— that requires software to run in order to be useful and accessible. Paper does not solve that problem.

JON:

But in terms of historians and countering the Ozymandius effect— paper…

VINT CERF:

You’re going down a blind alley here. If you think that the historians only need static information, you're dead wrong. Because an increasing amount of information is found in databases that can’t be printed out because they have a billion lines [of code]. So absolutely do not be fooled into thinking, “All I need to do is to print out this data.”

JON:

I’m just talking about preserving personal history.

VINT CERF:

We’re in complete sync on that. The scary part is that it's not enough to just print on paper, even though for some things paper is fine.

I print out a lot of stuff right now, [including] some emails I consider to be particularly important. I stack them up in my basement, because I know that will last more than 20 years.

…absolutely do not be fooled into thinking, “All I need to do is to print out this data.”

JON:

I want to ask you a trivial question because you're wearing a coat and tie today, and you come out of an industry famous for no ties. But I read that you were rebuked when you were at IBM for not wearing a white shirt one day.

VINT CERF:

This is true. It happened in 1965. And so I got rid of all my colored shirts. Now I replenish my yellow shirts, blue shirts and white shirts. The three piece suit has been a trademark for me for the last 45 years. Even in high school, I had a sports coat and tie and carried a briefcase and I did it on purpose because I wanted to be different—you know, instead of wearing gold braids or having long hair. So I sort of persisted in that style.

JON:

When you and Bob Kahn founded the Internet in 1973, was there an “Aha” moment where you're working on these packets and one day you go, “We've got it now!”

VINT CERF:

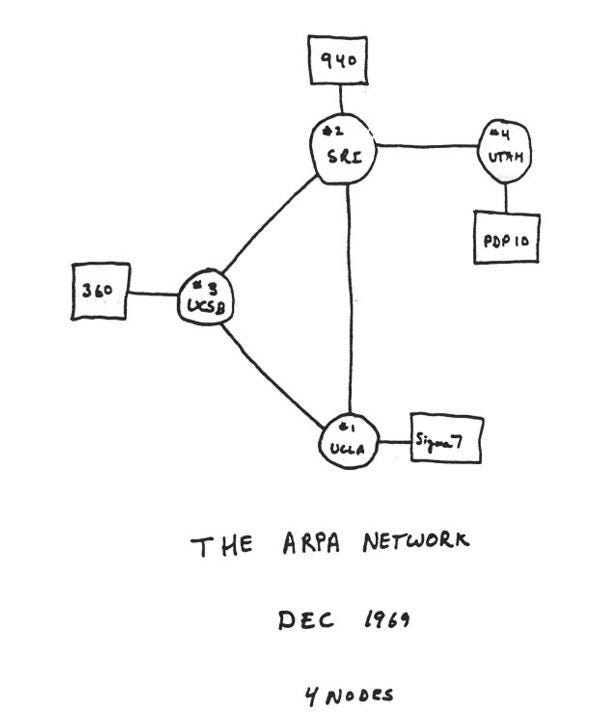

No, absolutely not. This was an engineering effort--not like discovery. This is more like, “I have a problem. What are the boundary conditions of the problem and what solutions could work?” The ARPANET had been based on packet switching and it was intended to be a resource for sharing time on different brands of computers, which was a hard problem to solve.

JON:

Getting these different brands and machines to talk to each other?

VINT CERF:

The challenge here was that there were many different companies making computers and we had quite a different collection of them on the ARPANET because of the various universities that were being supported by [the government network]. There were more computer companies then. [Our intention] was to allow researchers to share each other's software and computing capability across the network, instead of having to buy new computers every year for everybody.

JON:

Is it fair to say that the larger goal of DARPA was survivability in case of a nuclear war?

VINT CERF:

No, that’s a confusion with a 1962 RAND Corporation report focused on post nuclear attack survival. Bob [Kahn] had gone to DARPA in 1972 and now the question was, having demonstrated the utility of computer networking, can we use the computers to assist us in command-and-control? It means you're doing both numeric and non- numeric computation, including voice, video and data. How do we build networks that don't lose airplanes, mobile vehicles, ships at sea? So we then had to develop packet radio for mobile communication—airborne and ground base—and satellite communication, especially for long distance ships at sea. [Then we had to figure out] how do we hook all these different kinds of packet switch nets together and make the whole shebang work.

There is a wider range of challenges associated with using multiple networks with different bandwidths, different data rates, different delays and latencies and so on. So that was the Internet challenge.

JON:

Right, so then it's not til the 1980s—10 years later— before the rest of us can go on the Internet. Why did it take so long before it left the government and academia and became something that the whole world could use?

VINT CERF:

It was not easy to figure out how to make it work. It took a small group of us four iterations of protocol design [before] ultimately ending up with this TCP and IP split that was capable of supporting video and voice and data. I spent five years or so promoting implementation of the protocols on various computer operating systems, getting it done at IBM, Hewlett Packard, and Digital Equipment Corporation in their research labs.

And around then we’re starting to see some European interest in this, in spite of the fact that there is a huge collision that began in 1978 and we were in conflict over what was going to be the international standard until about 1993.

JON:

Wow, but you guys won. If you had lost, how would the world be different?

VINT CERF:

Well, you'd be running a different suite of protocols. They would probably work, but they would be much more complicated and elaborate and in my opinion, they'd be more clumsy. Your email addresses would not be anything as simple as we have today. They [European protocols] were just horrendous. There was something just overbearing about the seven-layer design that they pushed. We won only because we had real world experience and real products and services.

You got to Google in 2005 which was just a year after Gmail was developed. When you look back at the last 16 years there, what would you tell your grandchildren about what it’s like? What stands out for you in that period in terms of your own contributions and the way the world changed?

VINT CERF:

Well, you know I got hired as the Chief Internet Evangelist, a title I didn't ask for. They asked what title do you want and I said: “Archduke.”

JON:

Just as long as it’s not Archduke Ferdinand [whose assassination in 1914 kicked off World War I].

VINT CERF:

So my primary responsibility has been to work hard to get more Internet built all around the world and to try to make it more useful for people. And that's very consistent with what Google is trying to do. So I don't want to claim too much credit but I spent a lot of time helping to get policies adopted that would facilitate the development and implementation of more Internet.

I still have a long ways to go, of course, but people like Elon Musk putting out the SpaceX Starlink satellites is a big help. It's affordable for people with the 5G and 4G mobile phones that have had access to the Internet, starting in 2007. We're still only 50 percent penetrated.

JON:

Now it’s Google's time in the barrel. Do you think we're headed for Google and other tech companies being regulated like public utilities?

VINT CERF:

It’s hard to tell how this will pan out. There’s the antitrust assertions on one side. Then there is the concern about misinformation and disinformation and social media and its side effects. My hope, frankly, is that the more transparent we can be about how our systems work, the more we can dispel the belief that we're doing some pernicious thing.

The problem of misinformation and disinformation is extremely hard to deal with. If you say, “We should suppress it,” well, now you’re going down a very slippery slope. And what is it that gets suppressed? There’s a debate right now about Apple's attempt to deal with child pornography. The problem is that the thing [tool] that they have developed has the potential to be used as an extremely suppressive way by other governments.

This is like every other common infrastructure— you can abuse it. Think about automobiles and the road system. People get drunk and drive and they kill other people or themselves, or cause property damage, And you don't stop having cars and you don't stop having road systems because of their economic value, but you do introduce enforcement of law in order to manage misbehavior. I can imagine attempts to do something like that, but it's not easy. Suppressing information almost never is the right answer.

JON:

It’s not necessarily suppressing information, just providing different incentives, changing the algorithms so that the bad information doesn't rise to the top just because a lot of people are clicking on it.

VINT CERF:

Yes, we’ve taken steps to do things like that and we’ve de-monetized a number of things, put some boundaries conditions on what gets monetized. For example, we tried to reduce the ranking of content that we consider to be low value and increase the ranking of information we consider to be high value.

JON:

So I know you've talked a lot about wearables especially in the area of medical monitoring? Do you think that's going to be the big change of the next decade?

VINT CERF:

The pandemic has demonstrated the potential utility of remote medicine but that requires remote diagnosis. You can only practice medicine in the state in which you're licensed, but what if you’re in Virginia and your doctor is in California and you're doing this remote thing? So we'll have to figure out how that's going to work.

JON:

And the Internet of Things will expand.

VINT CERF:

The Internet of Things will certainly proliferate—very convenient and scary as hell. The scary part is, they may not work the way they're supposed to. The webcams maybe invade your privacy. Maybe it's because somebody got into your doorbell.

The Internet of Things will certainly proliferate—very convenient and scary as hell. The scary part is, they may not work the way they're supposed to.

JON:

What do you think the odds are on the anti trust front that Google will be broken up in the next decade? AT&T was broken up in the ‘80s, and a lot of innovation resulted.

VINT CERF:

I don't understand what the outlines would look like for breaking the company up, to be honest. How you do that in a useful way?

JON:

We’re going to be hearing more about this, no doubt.

Thanks, Vint.

In the early 20th century groundbreaking inventors, technologists, and scientists were lionized - e.g. Bell, Marconi, Wright(s), Tesla, Ford, Edison, Einstein, Lindbergh, Earhart. Then came WWII - and technology was no longer the province of mythical heroes. Who remembers Philo T. Farnsworth, the inventor of television? Or Arnold F. Wilkins, et al, the inventors of RADAR? Have we lost the ability to be amazed?

The formatting on this interview is backwards: Cerf's answers should be in bold, and Alter's questions should be in normal font.