Ruminating with TOM BURRELL

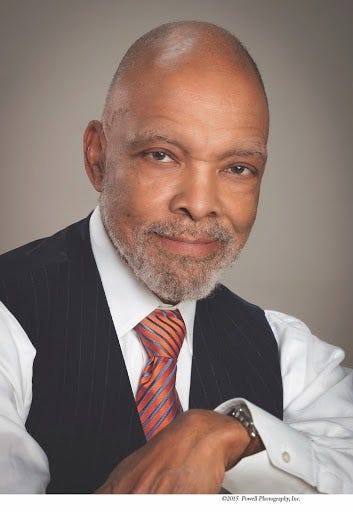

Pioneering founder of the largest Black-owned advertising agency, on being Black in the “Mad Men” era, and the first anniversary of George Floyd’s murder.

I first met Tom Burrell in 2008, when his fellow Chicagoan, Barack Obama, was running for president. Burrell, inducted in 2005 into the Advertising Hall of Fame, had made his reputation in the 1960s by recognizing that marketing to Black consumers was fundamentally different from other advertising campaigns and by showing that Black models and actors could successfully sell mainstream products to white America.

Burrell watched with admiration as Obama sold himself to white America. For my second Obama book, “The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies,” he explained to me how Obama interrupted the usual cycle of racial recrimination by not rising to the bait, thereby making himself a smaller political target. If Tom was impressed with Obama’s dexterity, I was impressed by Tom’s shrewd analysis of that dexterity.

Tom grew up in Chicago and graduated from Roosevelt University in 1962. During the 1960s, he worked his way up from the mailroom. He moved up through four major agencies, junior-copywriter to copywriter to supervisor. Although becoming legally blind in the mid-sixties, he started what eventually became Burrell Communications in 1971.

Burrell became the largest and most prominent Black-owned agency in the world. After retiring in 2005, he went on to pursue other creative endeavors including recording a vocal album, writing lyrics, and writing the notable book Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority. He also began writing and speaking on subjects of media literacy. Now 82, he and his wife, Madeleine Moore-Burrell, recently retired to Florida.

JON:

Hi, Tom. Thanks for joining me.

Just how white was advertising when you got in?

TOM BURRELL:

When I got in, there was nobody else [Black] in Chicago working in a big advertising agency in any capacity. When I say ‘any capacity,’ I mean, secretaries, receptionists. In New York, they had a few secretaries, but as far as advertising guys, there were only about three to six.

JON:

I hear you wore a double breasted suit even when you were in the mailroom.

TOM BURRELL:

I took my coat off once I got to work. I was very, very, very tight, you know. I had my clean white shirt, tie, and so forth. And the whole strategy was to always look like I didn't belong in a job, to elicit the question, “What the hell is he doing in the mailroom?” So by the time that I was able to walk into the creative director's office and tell him that I had aspirations to join that department— and I had some work to show him— it wasn’t implausible.

“… the whole strategy was to always look like I didn't belong in a job, to elicit the question, ‘What the hell is he doing in the mailroom?’”

JON:

I've noticed that Black guys who become successful in various realms are always better dressed than the white guys.

TOM BURRELL:

That is just basically symbolic. It goes all the way back to the feeling that you had to be better at everything—better dressed, more courteous, more pleasant and friendly. The whole idea is we have to overcompensate and be extra this or extra that.

JON:

Your most famous line is, “Black people are not dark skinned white people.” What did that mean and why did that work for you?

TOM BURRELL:

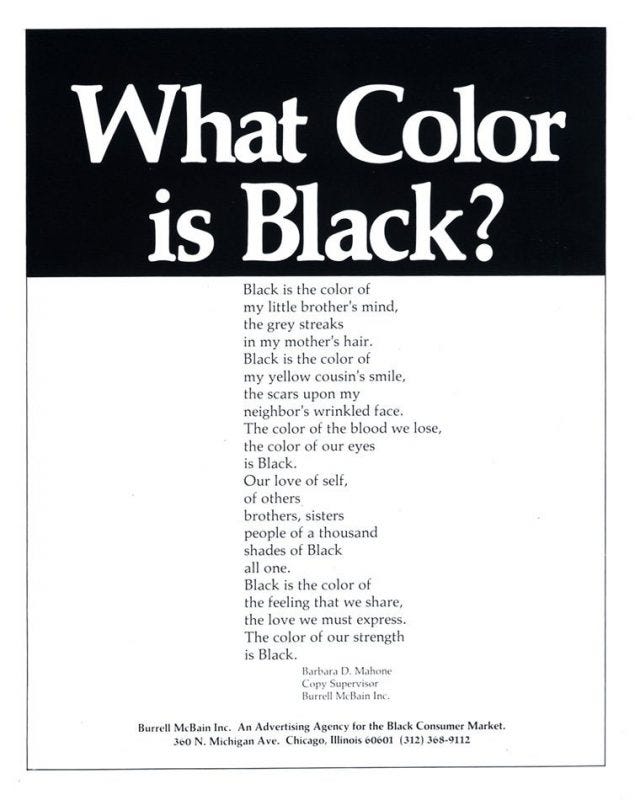

The unique selling proposition was that clients need to come to us because we know how to sell to Black people who are different because they live differently, they came to this country differently, are treated differently. And out of that came a lot of different attitudes.

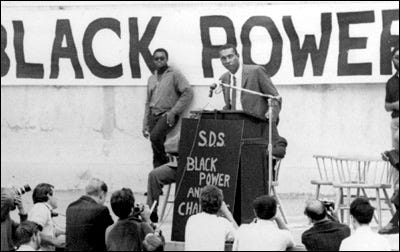

In 1966, Stokely Carmichael yelled out the words, “Black Power.” That became the genesis of a whole cultural thing in and of itself: his visceral appeal; the handshake; you had an Afro-centrism going on, with wearing dashikis. Carmichael was basically saying being Black is enough, and you don't have to do the rest of it [integration] in order to be equal, or to demand and expect justice. And that was the beginning of this whole idea of black people being different. It's okay to be different. And it's okay to shout out that difference and be proud of it.

JON:

How did you convince major clients to let you for the very first time go into network television with Black-themed commercials?

TOM BURRELL:

We had to dispel this whole idea that if commercials with black people ran in white media, then white people would be turned off. I had to make a promise to them that we knew enough about white culture because we'd had to live in it.

JON:

And Black culture was changing.

TOM BURRELL:

Up until that point, agencies or entities like magazines were basically saying that black people are by insinuation more like white people. We're all alike, and you still get some of that thinking today: “We're all the same. I don't see color.”

But everything was suddenly going the other way, and if it hadn’t been for the New Black Consciousness, then we would not have black agencies or black magazines or other media outlets that were based on that whole premise that we were unique.

So that's where this whole idea that “black people are not dark skinned white people” came in. We told our clients that they need to address those differences in order to be effective.

“Black people are not dark skinned white people.”

We also found we could do black targeted advertising that would also appeal to a white audience. One commercial communicating at separate levels. It's like many of today's animated motion pictures where there is a message within one movie sending one message to adults and another to the kids.

The commercials we innovated for network television worked pretty much the same way: Black people would see that deeper part of ads, while white people would look at it and say, “Oh, that's very entertaining. Oh, that's great. You know, that's very intriguing.” They would watch something like Black girls playing double dutch jump rope, or something else that they were not as familiar with, and be amused by it. Black consumers would see the same image and say, “They’re talking about us. They're talking about our history, our culture. our customs.”

JON:

Which big corporate accounts got this?

TOM BURRELL:

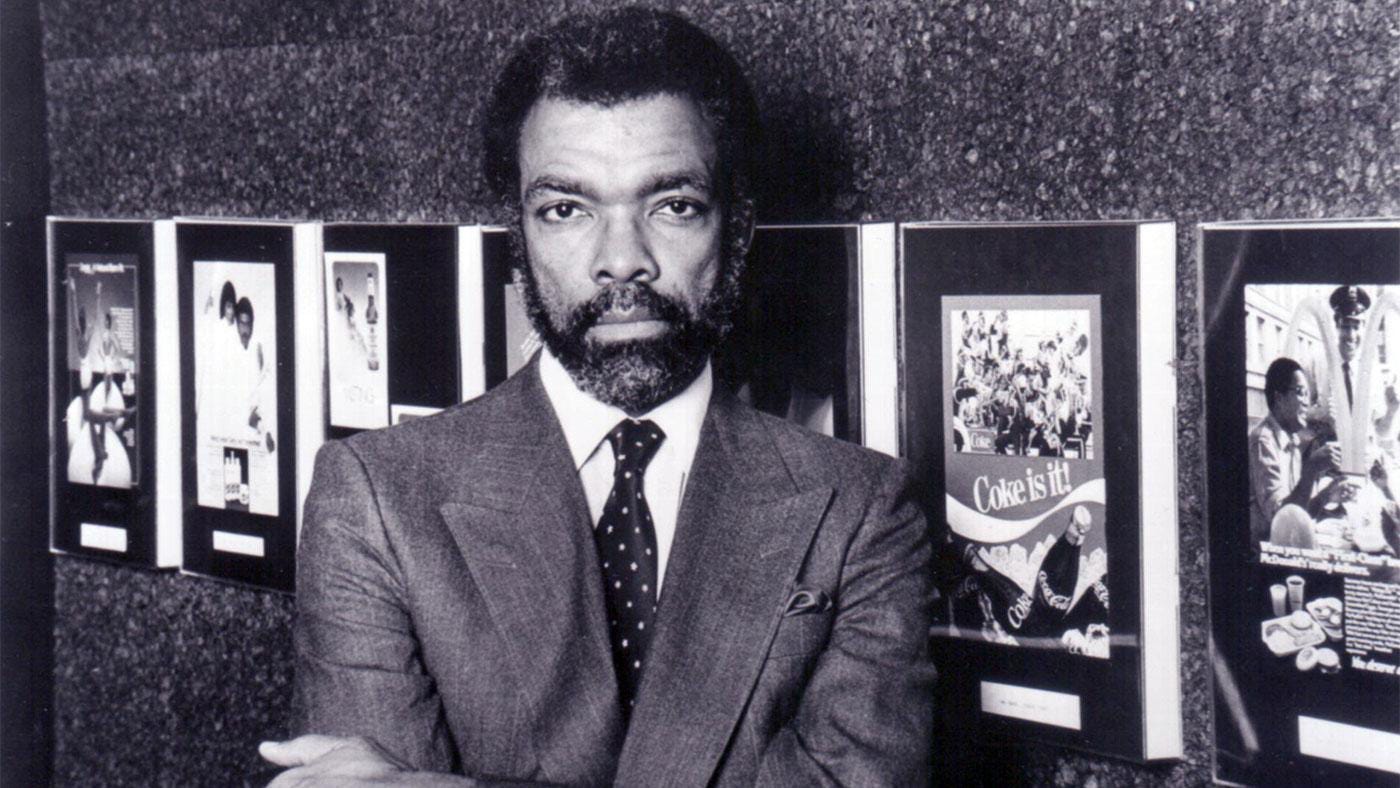

The first major account for us was McDonald's. The second was Coca Cola and then Procter and Gamble’s Crest and Tide Detergent brands. Forward, Sears and other blue chip companies followed.

Coca Cola’s ‘“Street Song” (1976)

McDonald's "Calvin Got A Job" (1990)

Lena Horne for Crest

JON:

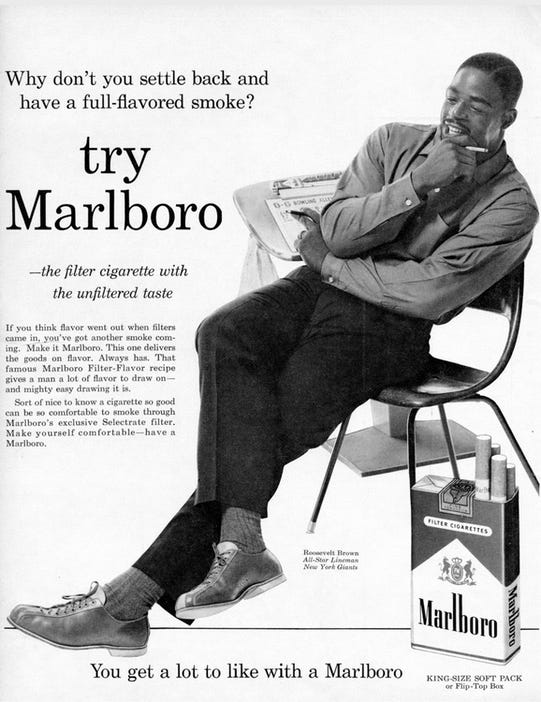

You also handled Marlboro for a while. Regrets?

TOM BURRELL:

I myself was a smoker. And I was not thinking about the idea of helping to kill people. But I did learn fairly early on in the game about the research the tobacco companies were doing on how to save a brand-- increasing consumption on the part of young black men, and looking at how do you get them into the market earlier. That’s when I decided to get out of advertising cigarettes.

JON:

It seems to me you were tapping into the fact that a very significant chunk of white America sees black culture as something they want to be a part of. That eventually became the juggernaut that is the NBA. You could make the same argument about a lot of music.

TOM BURRELL:

So, we have always had that role of being the creators of popular culture, but there was very little personal interaction with the people who created it.

I remember back in the ‘90s going down on Rush Street and seeing a bunch of white guys reciting some rap lyrics. And I realized that if they saw a bunch of black guys who created that music up close and personal, they would run to the other side of the street. It's this whole idea of admiring and emulating from afar.

JON:

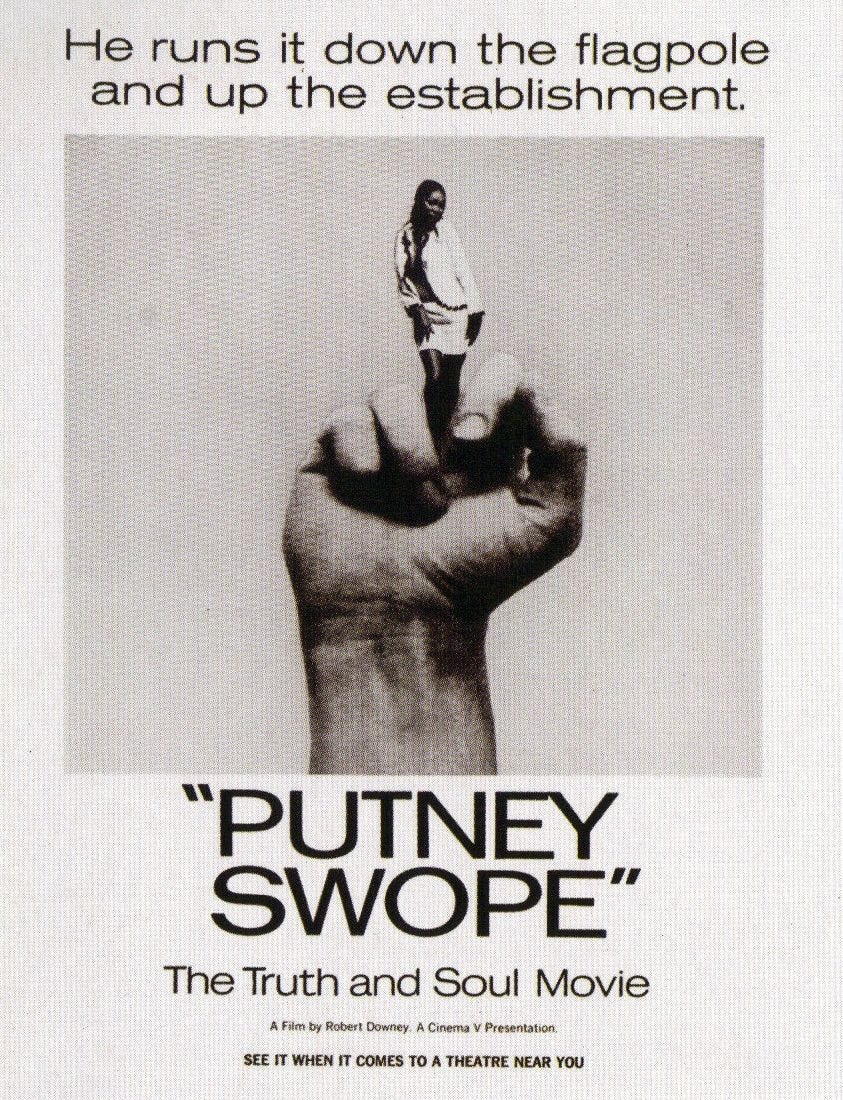

When I was a teenager one of my favorite movies was “Putney Swope,” where this rebellious Black guy somehow gets control of a boring white ad agency and fires everybody and puts on zany, radical ads.

TOM BURRELL:

When we first started, our first ad had us standing well-dressed like out of Mad Men in front of a coffin and the headline said: "Putney Swope is dead." It was a way of saying to corporate clients--"Don't get us wrong." We tried to set ourselves up as the opposite of what happened in that film, where a black guy with no qualifications takes over an agency and pulls great ideas out of his ass. Our whole thing is, we're bringing professionalism to this area--we do research and we're serious and going after serious business. We were saying we are buttoned-up professionals who will take good care of your business.

JON:

Some things are moving backwards. If Obama said today, as he did in 2004, “There is no red America. There is no blue America. Only the United States of America”—people would say, “What is he smoking?”

I sometimes think Obama's presidency will be seen in the context of reactionary politics, and how he represented the changing face of America, literally. That terrifies some people and not just when they think of Black people. It indirectly led to that Charlottesville “Jews will not replace us” chant. Replacement theory is getting big.

TOM BURRELL:

[Obama’s election] was a necessary thing— the tip of the spear to open things up.

But it’s like the plow that overturns the rock, under which there is all this stuff going on— all this fear and hate.

JON:

Was Obama too early, as he has suggested?

TOM BURRELL:

I don't think there will ever be a time in our lifetime that will be the “right time” for a Black president. It may happen again but it will always have significant issue value [for opponents]. There is this tremendous fear going on among the majority who sees itself becoming the minority, not only in terms of race, but in terms of attitude.

“I don't think there will ever be a time in our lifetime that will be the “right time” for a Black president.”

JON:

Isn’t it ironic that a black president is not able to openly be as big an advocate for black progress as a white guy? Because, if he's black, he's supposed to be “the president for all the people.” He’s not supposed to say “Trayvon Martin could have been my son.”

TOM BURRELL:

It’s almost like Obama’s tan suit. The slightest little thing.

JON:

To me, one of the big stories of recent years is how disciplined Black Lives Matter has been. For all of the right-wing nonsense, this very decentralized movement stayed non-violent.

TOM:

Based on our history it is not that surprising. Discipline has been the third strand between freedom and enslavement. We always wrestle with discipline vs action. There has always been a case for either side. It just leads to stress—that we can't be outraged by outrageous things.

JON:

After the Derek Chauvin verdict fades, are we gonna go all the way back to the blue wall?

TOM BURRELL:

I don’t think that generally we will go all the way back because it is going to be more and more difficult to get away with the collusion that has always taken place, especially since the advent of modern policing. All of the technology, body cams, mobile phones and other truth revealing developments will make it more difficult to hold up that wall. But…old habits die hard.

It’s an ongoing struggle but you hope there’s gonna be some cops who will think twice before they do the kinds of things this guy Chauvin did. Others will continue to do it but more secretly. The way George Floyd fell let the world see the key portion of the torture. Just imagine if his head and shoulders had been more behind the wheel of the car; we wouldn’t have seen it. There would have been no way for the young woman’s cell phone to pick up the critical image that went all around the world and ultimately led to the conviction.

JON:

So much of life is about inches. It would have been as if it never happened.

TOM BURRELL:

And nothing would have happened afterward.

JON:

I see the verdict as necessary but not sufficient. What worries me is that some white Americans may react the way they did to the election of Obama — “OK, we did it, we took care of that problem. There’s no prejudice when people are voting for president. That’s been established.” And now they’re gonna go, “OK, we took care of that black injustice thing—they were convicted in the George Floyd case.”

“It’s an ongoing struggle but you hope there’s gonna be some cops who will think twice before they do the kinds of things this guy Chauvin did.”

On the other hand, to be more hopeful, there’s some progress—bills in more than 20 states on things like choke holds and body cams. And people may take inspiration from this case and just start rolling in any situation they witness. They already do. There seems to be a tape nowadays of everything. I’m hoping at some point there’s a deterrent effect, where police officers go, “I’m not Derek Chauvin. I’m not a bad guy. But somebody is watching me pretty much the whole time, so I better clean up my act or I might lose my job.” We’re not there yet. Still too many poorly-recruited, poorly-trained officers.

TOM BURRELL:

There will be people who are so sinister — sadistic — that they will try to find a way to inflict pain undetected. It’s not a matter that this guy went through a traffic light or there’s a warrant for that person’s arrest. It’s that ‘I need to kill somebody today.’ In the Laquan McDonald case, he was moving away from him [the cop] and he shot him 18 times. And it’s a big victory that we’re supposed to go out and celebrate because he got six years. His intent was to kill the guy. Not stop him. Kill him. No bill is going to change that.

“It’s not a matter that this guy went through a traffic light or there’s a warrant for that person’s arrest. It’s that ‘I need to kill somebody today.’”

JON:

Did you see that video of the guy who is a consultant to police departments and he talks about the great sex you have after you shoot someone? And how about that torture house in Chicago. That wasn’t somebody snapping. It was premeditated torture by Chicago police not too many years ago.

And the firepower they have now is amazing—all this gear that was sent after 9/11 to fight terrorists. When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. They need new rules on drawing your weapon. It should be exceedingly rare. I once talked to a white cop who had spent 25 years in the South Bronx. He was really in the shit there in the Eighties but only drew his weapon once in all that time—to fire a warning shot.

TOM BURRELL:

Whatever happened to warning shots?

JON:

Good question. That cop was telling me,“Look, if you’re using your gun, you’re failing as a police officer.” Do they teach that at the police academy? That you should want to go through your whole career without using your weapon? I seriously doubt it.

“Whatever happened to warning shots?”

TOM BURRELL:

Believe me, there’s a bunch of people who go through the year and say, “Dammit, I haven’t had a chance to use my weapon all year. My hammer is a nine-millimeter. Gotta justify my existence here.”

JON:

You became legally blind when you were in your 20s. How did you cope with that?

TOM BURRELL:

It was discovered when I was 27 and in a business where eyesight was kind of important. One of the great things about macular degeneration is that it's the loss of central vision, not peripheral vision, so it's unlikely the person will ever go permanently blind. I was just very grateful that I wasn't being sentenced to total blindness. I basically used my peripheral vision to see. I adopted the term 'look harder." And by looking harder, I saw things other people didn't see. I found all the tools I needed.

If Stevie Wonder could do all the things he did totally blind, I could do a lot legally blind. I used enlargement machines, then computers to compensate. I now have 1500 books on Audible and Kindle, which has text-to-speech--I carry my library in my cell phone. I can have my email go to voice. So I work around the disadvantages--and that's the way I have lived my life, including now as an 82-year-old Black man.

JON:

When we talked earlier, you had a good take on why the cut-off for “Old Goats” should be older than 50.

TOM BURRELL:

It takes time to gain experience, perspective, independence. I’m not selling anything. I’m not looking for anything. I don’t have any ulterior motives. I’ve got a wonderful family, wonderful wife. And I can do what I want to do. I can say what I want to say. That’s how you get to wisdom and are free to impart it.

JON:

Thanks, Tom.

What an amazing career Burrell built! And, thanx, Jon, for reminding me about Putney Swope. I loved that movie!