Ruminating with TODD PURDUM

Star reporter and expert on the history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act and answer to a "West Wing" trivia question.

I can’t remember where I first met Todd Purdum—likely on the press bus of Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. He became a top reporter for The New York Times, covering the Clinton White House. Todd later married Dee-Dee Myers, Clinton’s former press secretary (the first woman to hold that position), and their romance was the basis of Danny Concannon's (Timothy Busfield) relationship with C.J. Cregg (Allison Janney) on “The West Wing.” Todd went on to write for Vanity Fair and then The Atlantic.

I’ve envisioned this newsletter as containing a lot of historical perspective and Todd is a good person to provide it on today’s voting rights battle. His 2014 book, “An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” is a model of historical narrative. The degree of difficulty in writing about a bill—even a famous one— is very high. Todd surmounted it.

This is the third rumination in a row with a fellow native Illinoisan (Todd now lives in Los Angeles; I live in New Jersey). That’s a coincidence and I promise more geographical diversity in the weeks ahead.

JON:

Hi, Todd. Thanks for chewing the cud with me.

Let's talk about HR1 and these state bills with a little historical context. You covered voting rights when you were in the Washington bureau of The New York Times and wrote a great book about the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Why didn’t that and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 get it done? Why are we still arguing about this more than a half century later?

TODD PURDUM:

Hi, Jon — Good to be ruminant with you!

In some ways, the question you ask - why did the landmark civil rights acts of the Sixties “not get it done” — is really the question of the moment. At the time those laws were passed, a hundred years after the Civil War, the general consensus was that removing the legal barriers to equality of opportunity might at last redeem the promises of the country’s founding creed.

It turned out that the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act were indeed necessary, but not sufficient, to produce that result. Changing the laws did not really manage to produce equality of opportunity — in part because of the lingering legacies of slavery and Jim Crow.

“In some ways, the question you ask - why did the landmark civil rights acts of the Sixties “not get it done” — is really the question of the moment.”

And changing the laws certainly did not result in equity of condition for black and white Americans. To tackle that problem, policy makers and lawmakers soon enough shifted their strategy to promoting corrective measures — like affirmative action — that had been explicitly rejected during consideration of the ’64 Act.

And in turn, that change—and the assassinations and civil unrest of 1968—ultimately had the effect of helping to splinter a bipartisan, bi-racial consensus on civil rights that was already pretty fragile. In some senses, we’ve been trying to dig ourselves out of the failure of that consensus — and the collapse of that hopeful moment — ever since.

JON:

But we did have at least a pro forma consensus in Washington for 40 years. In 1975, I was an intern in the office of Sen. Adlai Stevenson III of Illinois. My parents had worked together on his father's 1952 presidential campaign and married that year, and even though I was only 17, my, yes, privilege, got me an internship. That year, Congress, on a bipartisan basis, extended and expanded the landmark 1965 bill. The new section 2 of the bill banned any discriminatory voting rules, even if there was no intent to discriminate. (Another section extended voting rights protections to those for whom English was not their first language). The Voting Rights Act was extended a few more times--as recently as 2006--on a bipartisan basis.

I guess maybe the Supreme Court's awful 2013 decision in Shelby County vs. Holder weakening the Voting Rights Act gave white conservatives a permission slip to come out of the closet. And Karl Rove played a role, right?

TODD PURDUM:

Ah, Jon — we’re fellow Illinoisans, and proud of it, with lineages on opposite sides of the aisle. While your parents were going madly for Adlai (and, happily, for each other) my college-age mother was attending the 1952 Republican Convention in Chicago, where her family were rabid [Robert] Taft supporters. The journey the generations take on their way to adulthood...

Yes, I think the wretched Shelby County decision was the break that’s put us in such a painful bind right now, and emboldened white conservative recidivists all over the land. As you say, a bipartisan consensus on the Voting Rights Act had endured in Congress through repeated extensions. And so had the law's “pre-clearance” provisions requiring Justice Department approval of changes in voting procedures in covered jurisdictions — which, by the way, had long included parts of New York City, not just the Deep South. Shelby paved the way for states to backslide with impunity.

“Yes, I think the wretched Shelby County decision was the break that’s put us in such a painful bind right now, and emboldened white conservative recidivists all over the land.”

And that was, yes, the result of a very deliberate project of judicial and legislative strategy led, in places like Texas, by people like Karl Rove. Chief Justice John Roberts’ blithe pronouncement in the Shelby case that the way to stop discriminating on the basis of race was to stop discriminating on the basis of race — which he used to justify the Court’s gutting of the pre-clearance provisions — was disingenuous in the extreme.

At the same time, though, an underlying problem was that Congress had failed — and has since continued to fail — to adjust the various criteria that triggered the Voting Rights Act’s provisions, and that, in some cases, had fallen out of date. So it’s that gap that the Democratic-led House of Representatives sought to address in the bill it passed in 2019, the John Lewis Voting Rights Act (not to be confused with HR1—the For the People Act, which tackles a broader array of election problems). But so far, the House hasn’t re-passed that bill and prospects in the Senate remain grim.

JON:

Joe Manchin has a Senate bill to extend the Voting Rights Act and do it on a bipartisan basis. He even has some Republican support for it. But apparently it’s unconstitutional.

TODD PURDUM:

As I understand it, the threshold problem is that Manchin’s proposal to expand the “pre-clearance” element of the Voting Rights Act to the whole country is that it would run afoul of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelby. The Court’s argument then was that the law’s section 5 pre-clearance requirements were out-of-date in some jurisdictions, because conditions of systemic discrimination in those locations had improved.

So the Court suggested too much of the country was covered, as things stood.

JON:

And Manchin’s bill says too little of the country is covered, the point being that the South shouldn’t be singled out as it had been in the past—an idea that he hopes attracts Republicans.

TODD PURDUM:

To pass muster with the High Court, any attempt to reinstate pre-clearance would seem to have to be evidence-based and carefully tailored to specific jurisdictions, and Republicans have not shown any interest in this approach.

So the Manchin idea—billed as a compromise that could draw bipartisan support—would seem to contain the seeds of its own failure, if not in Congress, then at the Supreme Court because the bill wants to cover more jurisdictions, indeed the whole country.

JON:

That’s great. Just great. Jeez. The one guy we need has an unconstitutional bill.

TODD PURDUM:

There’s a respectable argument that this approach would be constitutional, but it’s harder to see how this particular Court would agree.

JON:

So that leaves few options unless Democrats are willing to amend the filibuster. You’re actually an expert on the filibuster because the one against the 1964 Civil Rights Act was the longest in history and you chronicle it in your book. (There was no filibuster against the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because the bill moved rapidly to passage after John Lewis and others were beaten in Selma and LBJ’s famous. “And we shall overcome” speech.)

Since we're both native Illinoisans--or Illini--let's talk for a sec about Everett Dirksen, the distinguished GOP senator from Pekin, Illinois (I won't repeat the name of their high school teams because for many years it was an ugly anti-Chinese slur). Pekin is like Vi-enna, Cay-ro and other Illinois towns named after world capitals and mispronounced (that's a thing in Illinois: Goethe Street in Chicago is pronounced "Go-Thee" not "Gur-ta," as it should be).

Anyway, why did Dirksen (also famous for supposedly saying, "A billion here, a billion there, pretty soon you're talking about real money." -- in need of updating to "a trillion here...") -- why did he come around on calling off the filibuster? And over on the House side, remind me about Rep. William McCullough, a Republican who did the right thing. Is there any hope for that today?

TODD PURDUM:

Everett Dirksen, the Wizard of Ooze — a friend of my maternal grandfather's, as it happens. (I used to have a baby picture of myself autographed by the Senator himself, but lost it in a move, I think!) Pekin was, in the 1920s and beyond, a “sundown town,” a place where blacks were not welcome after dark.

And Dirksen was as conservative as they come on most issues of foreign and domestic policy. But he also took seriously the GOP’s heritage as The Party of Lincoln, and he had a creditable civil rights record. By 1964, he had become persuaded, in his memorable phrase (which he borrowed from Victor Hugo), that civil rights was “an idea whose time has come.” So he worked with Hubert Humphrey and Senate Democrats to shape the final bill to his liking, forcing a raft of comparatively minor verbal changes—enough that he could say he’d made X-number of revisions.

In intense negotiating sessions in Dirksen’s office, Democratic aides and Justice Department officials told me, the trick was to get Dirksen’s firm agreement to any changes before he’d consumed so much bourbon that he wouldn’t remember the next morning what he’d agreed to the night before. Because while it was easy enough to change language one time without changing the legal meaning, it got much harder on a second attempt! Dirksen also insisted on substantive changes that assured that northern states like Illinois —with their own strong civil rights laws already in place — would have first crack at resolving cases of alleged employment discrimination before the Feds stepped in.

“...the trick was to get Dirksen’s firm agreement to any changes before he’d consumed so much bourbon that he wouldn’t remember the next morning what he’d agreed to the night before.”

His Republican counterpart in the House — William McCulloch of Ohio — was really the great unsung hero of the bill, who steadfastly refused all attempts to weaken the law before it ever got to the Senate. He, too, was a conventional conservative in most ways, but a lifelong champion of civil rights.

Alas, there doesn’t seem much hope of finding a brave, bipartisan figure like McCulloch today, and just one piece of evidence makes the point: In modern times, McCulloch’s old district was represented by...John Boehner, whose recent memoir makes the somewhat pitiful case that he couldn’t have controlled the fire breathing crazies in his own caucus even when he wanted to — and he didn’t always want to.

JON:

Very depressing, though I still hold out hope for a carve-out from the filibuster--what I like to think of as "the democracy option" (homage to the nuclear option)--that would let the Senate pass bills related to democracy with 51 votes, just as they approve judicial and executive branch nominations on that basis. I know Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona are against it, but pressure on them is growing. I could see a modest but effective bill that barred some of the most egregious voter suppression ideas but let states handle many questions related to elections.

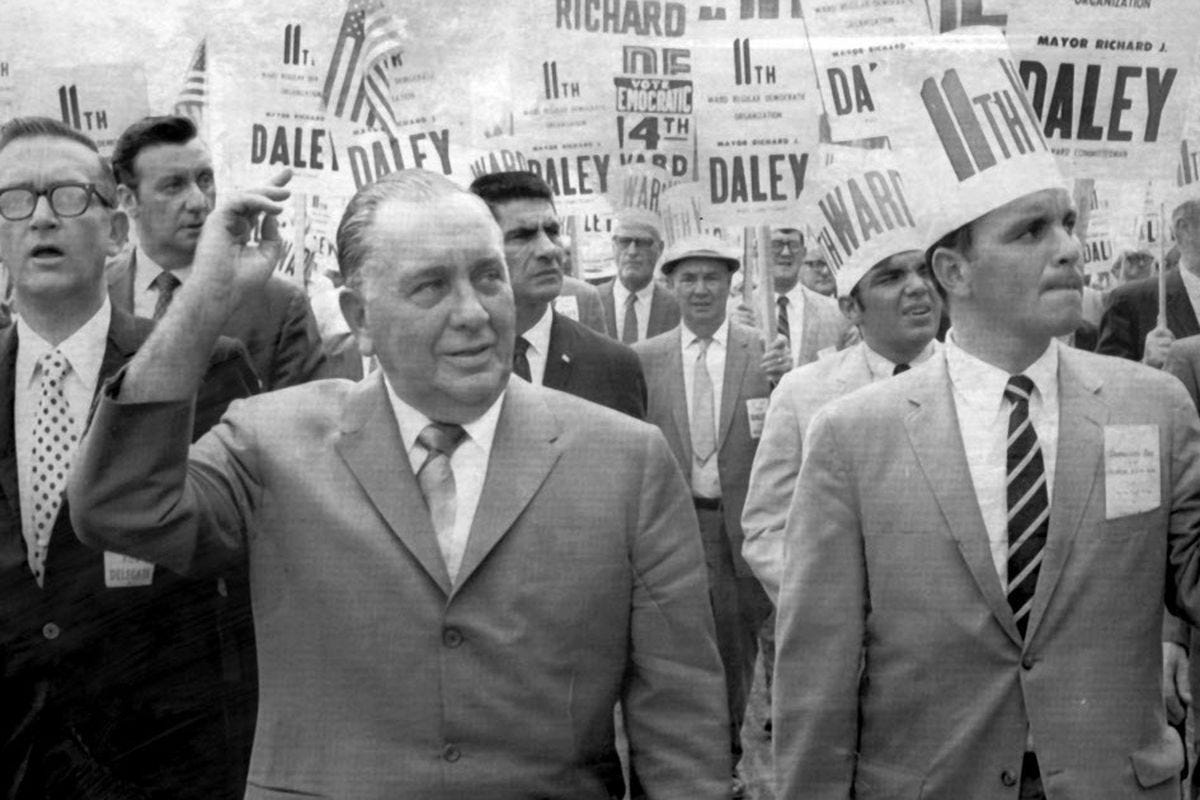

Just to bring the Dirksen and Stevenson stories together: In the fall of 1969, when I was 12, I went with my family to a Democratic Party rally and picnic at the Libertyville farm where Gov. Stevenson (who died in 1965) had lived when he ran twice for president against Ike. The event included reform-minded liberals who had broken with Mayor Richard J. Daley after the disastrous 1968 Convention in Chicago, where Daley's thuggish police bloodied demonstrators. Adlai III, the state treasurer, called the police "storm troopers in blue." Harsh words and presumably the end of any relationship with Daley.

Then something strange and, soon, exciting happened at the picnic. I remember watching a young, dashiki-wearing Jesse Jackson speak, and getting some cotton candy, when radio news spread through the liberal crowd that Sen. Dirksen, the Senate minority leader and top Republican in Illinois for many years, had died suddenly.

Not long after, someone passed the word: Daley is coming! The man Adlai had attacked--and we all loathed--was coming to Libertyville. Whaat?!? That had to be a bogus rumor. Even a 12-year-old knew that. But it was true. When he arrived, he walked right by me. I remember his dark blue suit and tie (everyone else was in jeans) and ruddy Irish face. He greeted Adlai warmly and everyone knew this meant that he would back Stevenson in the special election to fill the seat that fall, which in turn meant Stevenson would be Dirksen’s replacement in the Senate. It was like the passing of power in a royal court. I tell that story not only because it was so vivid for me as a kid, but because it shows what a skillful pol Daley was.

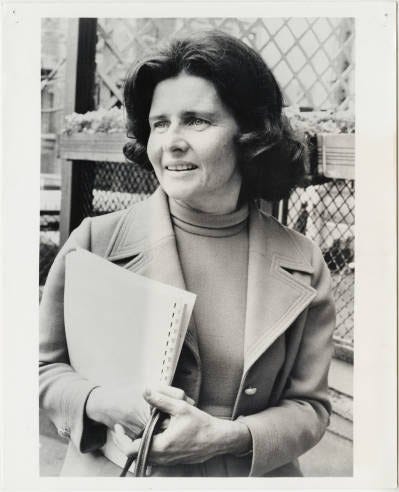

Two years later, Daley did the same thing--this time coopting his liberal critics by slating my mother, Joanne Alter, for commissioner of the Sanitary District. (Daley’s habit was to go to the Sherman House Hotel and decide on the ticket over lunch). When she told him she didn't know anything about sewage, he told her she would learn and asked: “Joan [He never got her name right], I thought you told me you wanted women in da party." She accepted and in 1972 ran as an environmentalist, led the ticket in votes, and became the first woman elected to office in Cook County.

Sorry for that tardy proud Mother’s Day tangent, but these struggles to expand democracy are long ones. When my mother broke that gender barrier, women had already had the vote for about a half century. The nearly 50 years since then have seen more progress than the first 50 years after women’s suffrage, but getting to Kamala Harris as VP has taken longer than it should have.

Final thoughts?

TODD PURDUM:

After the ’68 debacle, my solid Republican parents were in the Windy City from my hometown in downstate Macomb, and saw Da Mare crossing the street. I’m told my father called out, “We’re all for you, Mr. Mayor!” The things it hurts to confess.

A few months after you were at the picnic in Libertyville, I was at a 4-H picnic in Macomb, where the GOP candidate in that same special Senate election to fill Dirksen’s seat — a forgettable man named Ralph Tyler Smith — spoke. And who was working on Smith’s campaign? One Karl Christian Rove, the once and future Boy Genius of Republican politics.

I, too, hope either for a filibuster “carve-out,” or at the very least, a return to the “talking filibuster,” in which dead-enders would have to stand and deliver and not just declare that a particular proposal didn’t have 60 votes and thus send the Senate to the fainting couch of inaction. Mitch McConnell can fulminate about the risks for businesses who follow MLB’s lead on the All-Star Game relocation, but the truth is, it was grassroots activism — including activism by civic-minded, practical businesses — that helped create the groundswell of public support that led to passage of the landmark Sixties civil rights acts.

So maybe the energized reaction to retrograde developments like the Georgia law or Texas bill is just what’s needed to spark renewed public pressure on recalcitrant Congressional Republicans. I wouldn’t bet my family’s prime Illinois farm ground on that outcome, but for the first time in many a moon there does seem some reason for hope, no?

“I wouldn’t bet my family’s prime Illinois farm ground on that outcome, but for the first time in many a moon there does seem some reason for hope, no?”

Meantime, here’s my proposal for amending the last lines of our Illinois State Song: “On the record of thy years, Ab’ram Lincoln’s name appears, Grant and Logan and Obama, and our tears, Illinois…” Reagan may be the only president ever born in Illinois, but Obama remains just the second ever elected from there, after holding the Senate seat that once belonged to…Ev Dirksen.

JON:

Thanks, Todd.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story stated that the picnic on Adlai Stevenson’s farm was in the spring of 1970 instead of the fall of 1969. The story has been corrected.

_______________________________________________________

Great insight into the salient issue in American democracy today. Those who appreciate the founders' experiment must take a stand on voting rights now.

...sez the guy who wrote the book on Rodgers & Hammerstein!