I first met Mike Kinsley in the mid-1970s when I was on the Harvard Crimson and Mike—the brightest of a generation of bright young political journalists—was already developing a reputation as a gifted writer in the tradition of George Orwell. In 1980, as the legendary editor of the New Republic, he gave me my first major break in the business by publishing a few of my freelance articles. I went on to toil at the Washington Monthly, where Mike had earlier worked. Under Mike’s editorship, TNR was more influential than at any time since Walter Lippmann helped found it in 1914. At some point in the ‘80s, Mike coined what became a famous description of a gaffe: "A gaffe is when a politician tells the truth – some obvious truth he isn't supposed to say.” We just saw a Kinsley gaffe last week when President Biden said NATO was divided over how to respond to a “minor incursion” by Russia into Ukraine.

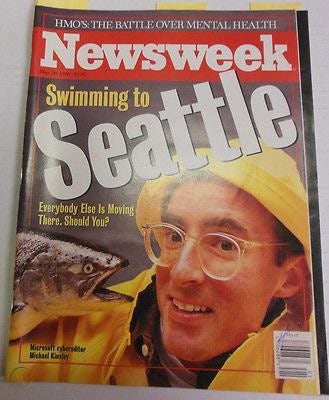

In 1995, Mike quit co-hosting CNN’s Crossfire and moved west to Seattle where he founded a Microsoft-backed publication he called Slate, the first real online magazine. (That’s where he met his future wife, Patty Stonesifer, the first chief executive of the Gates Foundation). He also served at various times as editor of Harper’s and editorial page editor of the Los Angeles Times, and he wrote regularly for Politico, Vanity Fair, the Washington Post, and Time, among other publications. For 20 years, he has suffered from Parkinson’s, which he depicted, with his usual wit, in a 2016 book.

Mike remains a mentor (though he no doubt hates the word) to scores of magazine journalists, including me. This week I’m republishing a prescient article he wrote in the Atlantic in 2010 about inflation. Instead of a broad rumination, we talk about that.

RIGHT-WING TALK RADIO these days is carrying fewer commercials for second mortgages. (Consolidate your debts, lower your monthly payments, and have enough left over for that dream vacation!) They’ve been replaced by commercials for gold. Gold bugs have long had a small place on the map of the American right, but to most people gold seems like a crazy investment. It doesn’t produce anything, unlike a company in which you might own shares. It can’t provide shelter, like a house. It’s too expensive to use widely in industry or commerce, except for tiny amounts that go into people’s mouths, wrap around their fingers, or hang from their ears. Gold just sits there. And yet the price of gold has gone from about $280 an ounce 10 years ago to about $1,140 today.

The only reason to buy gold is fear that the currency may collapse. Paper currency used to represent claims on a share of the gold in Fort Knox. Now it is just “fiat money,” backed only by the “full faith and credit” of the United States government. Ditto electronic money—the $5,000 you allegedly have in a savings account at the bank, whose only corporeal existence is on a hard drive somewhere. That $5,000 is $5,000 only because the government says it is. For the gold bugs, trusting the government seems as unwise as hoarding gold seems to most other people.

Another way to say “collapse of the currency” is to say “hyperinflation.” Hyperinflation is when inflation feeds on itself and takes off beyond control. You can have stable 2 to 3 percent inflation. But you can’t have stable 10 percent inflation. When everybody assumes 10 percent, all the forces that produced 10 percent push it to 20 percent, and then 40 percent, and soon people are lugging currency in a wheelbarrow, as in the famous photos from Weimar Germany.

Thirty years ago, we peered into this abyss and pulled back just in time. As inflation neared its peak of more than 13 percent, Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Using his control over the money supply, Volcker purposely plunged us into a deep recession, which is the only certain remedy. Carter got blamed for both the inflation and the recession that cured it. The columnist Robert Samuelson tells the story in his book, just out in paperback, The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath.

Even 13 percent inflation was a nightmare. A stable currency is firm ground on which you can build a life. Inflation turns life into Through the Looking-Glass: you have to run faster and faster to stay in the same place. Saving is for suckers, and money needs to be spent sooner rather than later. Planning even a year or two ahead becomes nearly impossible. Worst of all, economically, the hard knocks and lucky breaks of life, which people generally accept when they are distributed by fate, become politicized, and therefore embittering. Stop fighting, and you start losing.

Furthermore, as Samuelson notes, the damage is more than just economic. These days everyone is disenchanted with civic institutions and government. They hate the press, they loathe Congress, and so on. Studies by foundations puzzle over why. Was it the ’60s? No, it was the late ’70s and early ’80s, when government failed to deliver on its obligation to provide a stable currency.

Samuelson worries that “the entire episode” may “slip from our collective consciousness.” I’ll spare you the Santayana and just say that if we are doomed to repeat this particular bit of the recent past, the press has failed in its self-imposed obligation to be the “first draft of history.”

According to the considerable discussion of inflation on the Web, my alarm is misguided. Every economist I admire, from Paul Krugman and Larry Summers on down, is convinced that inflation will remain low for as long as we can predict. Greg Mankiw, who was George W. Bush’s economic adviser, has examined the evidence in his New York Times column and concluded that a return of debilitating inflation is pretty unlikely (although “current monetary and fiscal policy is so far outside the bounds of historical norms” that who can say for sure?). Krugman has charged that inflation fearmongering is a nefarious Republican plot. The Congressional Budget Office (usually known by its nickname, “the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office”) projects inflation rates of less than 2 percent for the next decade. Some say the real danger is the opposite: deflation, or prices (and wages) going down across the board.

Maybe I’m like those generals who are always fighting the last war, but I am not reassured. I worry that when and if the recession is well and truly over, there is a serious danger of another round of vicious inflation. (If the recession is not over, or gets worse, we’ll have other problems.) This time, inflation will be a lot harder to stop before it turns into hyperinflation. Whether Obama navigates these shoals successfully will be a big factor in his historic reputation. And journalists will be kicking themselves (and other people will be kicking journalists) for missing a disaster story on the level of Hurricane Katrina, if not 9/11 itself.

In short, I can’t help feeling that the gold bugs are right. No, I’m not stashing gold bars under my bed. But that’s only because I lack the courage of my convictions.

My fear is not the result of economic analysis. It’s more from the realm of psychology. I mean mine. The last time I wrote about this subject, The Atlantic’s own Clive Crook called me a “fiscal sado-conservative.” I would put it differently (you won’t be surprised to hear). Maybe, at least on economic matters, I’m a puritan. The recession we’ve been going through did not occur for no reason. Even though serious misbehavior by the finance industry triggered it, sooner or later it was bound to happen. For a generation—since shortly after Volcker saved the country, and except for a brief period of surpluses under Bill Clinton—we partied on borrowed money. We watched a real-estate bubble get larger and larger, knowing but not acknowledging that it had to burst. Then it did burst, and George W. Bush slunk off to Texas, leaving Barack Obama to clean up the mess. Obama has done the right things, mostly, pushing through a huge stimulus package and bailing out a few big corporations and banks. Krugman says we need yet another dose of stimulus, and maybe he’s right.

But this cure has been one ice-cream sundae after another. It can’t be that easy, can it? The puritan in me says that there has to be some pain. That’s not to say that there hasn’t been plenty of economic pain. But that pain has come from the recession itself, not the cure.

My specific concern is nothing original: it’s just the national debt. Yawn and turn the page here if you’d like. We talk now of trillions, not yesterday’s hundreds of billions. It’s not Obama’s fault. He did what he had to do. However, Obama is president, and Democrats do control Congress. So it’s their responsibility, even if it’s not their fault. And no one in a position to act has proposed a realistic way out of this debt, not even in theory. The Republicans haven’t. The Obama administration hasn’t. Come to think of it, even Paul Krugman hasn’t. Presidential adviser David Axelrod, writing in The Washington Post, says that Obama has instructed his agency heads to go through the budget “page by page, line by line, to eliminate what we don’t need to help pay for what we do.” So they’ve had more than a year and haven’t yet discovered the line in the budget reading “Stuff We Don’t Need, $3.2 trillion.”

There is a way out. It’s called inflation. In 1979, for example, the government ran a deficit of more than $40 billion—about $118 billion in today’s money. The national debt stood at about $830 billion at year’s end. But because of 13.3 percent inflation, that $830 billion was worth what only $732 billion would have been worth at the beginning of the year. In effect, the government ran up $40 billion in new debts but inflated away almost $100 billion and ended up with a national debt smaller in real terms than what it started with. Ten percent inflation for five years (if that were possible) would erode the value of our projected debt nicely—but along with it, the value of non-indexed pensions, people’s savings, and so on. The Federal Reserve is independent, but Congress and the White House have ways to pressure the Fed. Actually, just spending all this money we don’t have is one good way.

Compared with raising taxes or cutting spending, just letting inflation do the dirty work sounds easy. It will be a terrible temptation, and Obama’s historic reputation (not to mention the welfare of the nation) will depend on whether he succumbs. Or so I fear. So who are you going to believe? Me? Or virtually every leading economist across the political spectrum? Even I know the sensible answer to that.

And yet …

JON:

OK, Mike, you win the prescience prize. But it took 11 years before you were proved right. Why did it take so long?

MIKE KINSLEY:

First of all, Jon, I’m not rooting for inflation, though i can’t help feeling a bit smug about being “right too soon.” I’m not happy with inflation at 7 percent, nor should anyone be. How it got there is a little unclear. One obvious flaw in my prediction is that I failed to foresee the pandemic. To the extent that Covid can explain the huge deficits, which can in turn explain the new inflation, maybe that overwhelms the other factors.

JON:

You write that once inflation hits 10 percent, we're screwed. It will go to 20 percent and pretty soon we're Weimar Germany. Can Biden and the Fed keep it from going from 7 to 10 percent?

MIKE KINSLEY:

Well, they’re both going to try. But I’m a bit pessimistic. Unfortunately, it’s much easier to go from 7 to 10 than from 4 to 7.

JON:

I'm not as worried as a lot of people because of what I learned when studying the Carter-era inflation for my book. It didn't start zooming up until the 1973 Arab oil embargo and, later, the Iranian oil industry coming to a standstill after the Iranian Revolution. Energy prices went up 14-fold (not 14 percent) over the course of a decade--not something that's likely now, when we have much more energy independence than in the 1970s. Plus, for us "COLA" means a beverage; in the '70s it stood for Cost of Living Adjustments and they were included in wages, pensions, everything--embedding inflation in the structure of the economy. I’m guessing that because today's inflation is not super-charged by OPEC and COLAs, it will be easier to control, especially when supply chain disruptions ease. And raising interest rates from basically zero to even four or five percent is not likely to shut down the economy the way 19 percent interest rates did in 1980. So we might not need a deep recession to curb this inflation.

What am I missing?

MIKE KINSLEY:

I still suspect this inflation will have to be ended by a deep recession just like the last one.

JON:

Is that the only remedy?

MIKE KINSLEY:

Maybe not only. Technology [in recent years] has given us a few extra points of GDP, which could help. I can’t prove it, but at some point—if not 10 percent, then 15 percent—it becomes unstoppable….

JON:

Without jamming on the brakes the way [Fed Chair Paul] Volcker did.

MIKE KINSLEY:

Right.

JON:

How about my point about it being different in the ‘70s with COLAs and built-in, high-wage contracts?

MIKE KINSLEY:

Covid makes all of that seem minor.

JON:

Why?

MIKE KINSLEY:

What you’re basically saying, Jon, is that this one’s different. But there’s always gonna be something ‘different’. People will say, “Well, if we didn’t have Covid, there would be no problem.” In the ‘70s, they said, “If we didn’t have an Arab oil embargo, we wouldn’t have a problem.” There are always external factors. Something is always going to come along that allows people to explain [the inflation] away. The point is, there are inflationary forces at work that are new and powerful.

“But there’s always gonna be something ‘different’. People will say, “Well, if we didn’t have Covid, there would be no problem.” In the ‘70s, they said, “If we didn’t have an Arab oil embargo, we wouldn’t have a problem.” There are always external factors.”

JON:

But some of the differences seem important. We don’t have the “stagflation” of the ‘70s. Economic growth is very strong.

MIKE KINSLEY:

If you close down half of the economy [during the worst of Covid in 2020] and reopen it, you’re gonna get a spurt.

JON:

But doesn’t the fact that we’re starting this fight from a place of very low interest rates rather than high ones give us a little cushion?

MIKE KINSLEY:

I hope you’re right, though I’m not sure you are.

JON:

I hope I’m right, too. Thanks, Mike.

Another great piece. Please try to convince Mike to ruminate on other topics too! He always has an interesting take. And I was happy to see you mention his "mentorship" of you and other young journalists. He was very kind to me and to other recent Harvard grads (even non-journalists), when we arrived in DC while he was at The New Republic. We knew him from Kirkland House where he was a Resident Tutor. A smart and good guy.

Thanks, Patrick. I'm glad you reminded me that on top of everything else, Mike has always been a gracious guy. Re his talent, I'd like to clarify my comparison of Mike to Orwell. Mike has never written fiction and, unlike Orwell, he has never covered events abroad. But if Orwell had lived longer and moved to Washington, his take would sound a lot like Mike's.