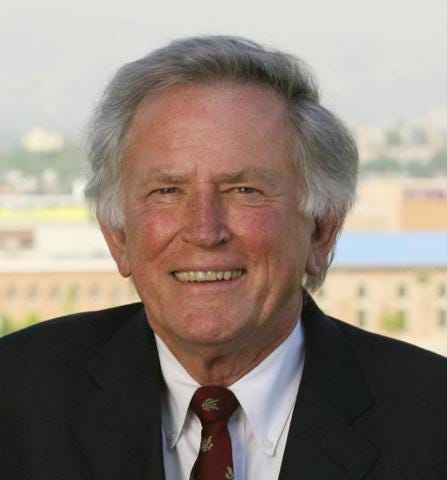

Ruminating with GARY HART

He talks for the first time about the scandal and the line between his political demise and Trump.

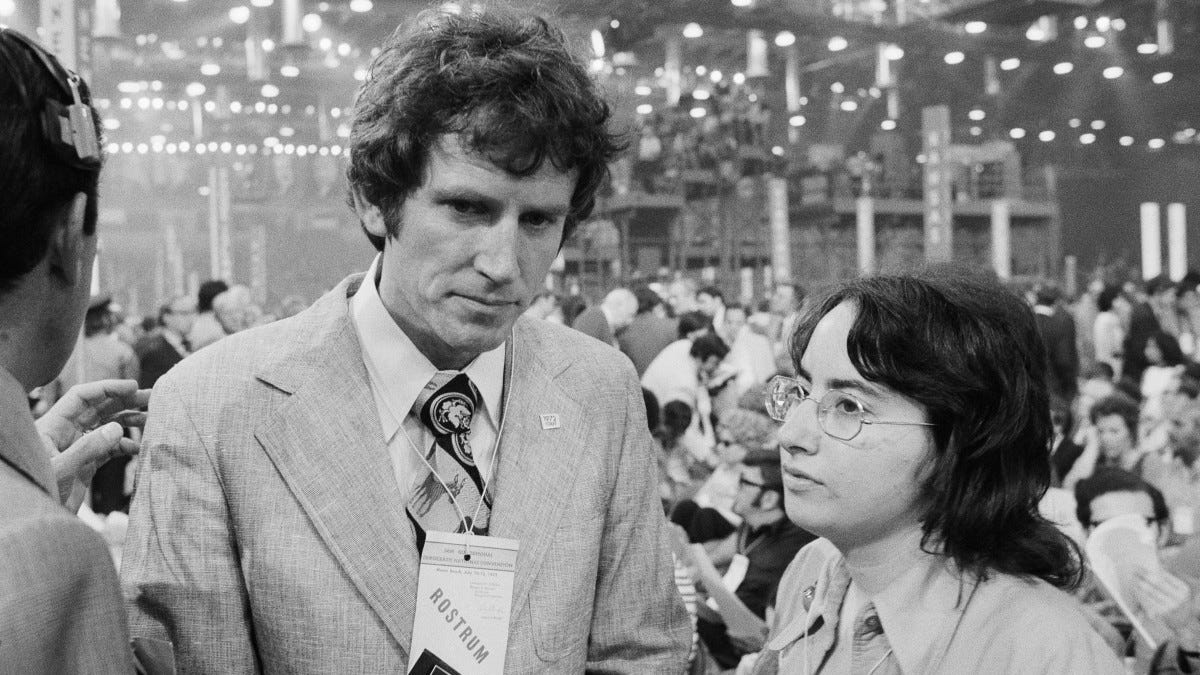

When I was in colIege, Gary Hart was the most exciting politician in America. Two years after managing George McGovern’s 1972 campaign for president, he got himself elected to the U.S. Senate from Colorado. I first met him in 1984, when, as a 26-year-old Newsweek reporter, I covered his presidential campaign in the period after his big, shocking victory over Walter Mondale in the New Hampshire primary. Despite Mondale’s famous and effective debate gibe, “Where’s the beef?” (borrowed from a Wendy’s ad), Hart really did have “New Ideas” (his campaign slogan) to move Democrats away from interest group liberalism and toward a more innovative future.

In 1987, when—as the front runner— he was forced to withdraw from the 1988 campaign in a titillating sex scandal, I wrote equivocal media columns about the contretemps. Even when we’ve disagreed, I’ve always admired his record in public life, his intellectual seriousness and his prodigious literary output—16 non-fiction works and five novels, including two under the pseudonym “John Blackthorn.” Hart is now 84 and his wife of 63 years, Lee, died in April.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Thanks for doing this, Gary. You must have had a rough spring and summer. My condolences.

GARY HART:

Thank you. Neither of us are spring chickens—Lee was 85 and had a botched hip replacement that really hindered her mobility. She was on a walker and things began to fall apart and that’s basically what happened. Otherwise, throughout her life she was very physical and could throw a football as far as most men.

JON:

I remember having a couple of wonderful conversations with her on the plane in 1984. Of the wives of the politicians I’ve covered, she was one of my favorites—so up all the time and easy to talk to.

GARY HART:

I got hundreds of emails and cards and letters from all across the country saying the same thing. People found her remarkable—unlike [so many other political spouses], she was a vivid personality in her own right.

JON:

Is it fair to say that the United States faced its first coup attempt early this year?

GARY HART:

It has to be considered a form of coup—an extra-constitutional effort to maintain power. I have been part of a group of former officeholders—elected and appointed—called Keep Our Republic.

During the campaign, we had contacts with several people from the National Security Council and with former senior command and flag officers about what would happen if President Trump refused to accept a negative vote. What would the Pentagon do? There was a lot of quiet discussion going on in military circles and with former officials in the Justice Department, including the national security division, where I had my first job out of law school. Some pretty serious people.

…we had contacts with several people from the National Security Council and with former senior command and flag officers about what would happen if President Trump refused to accept a negative vote. What would the Pentagon do?

JON:

What do think about what General Milley did?

GARY HART:

There’s much more to learn about this. There is no evidence in his career that he was flying by night or assuming authority he didn’t have. I think it would be a mistake if the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was operating all by himself. [But] anyone who can incite an insurrection that destroys part of the Capitol of the United States ultimately has to be taken seriously, and that’s what the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs [and others] understood.

JON:

Technically, the president has the “sole responsibility” to launch nuclear weapons. Do we need to change the law so the House speaker and president pro tem of the Senate need to sign off on it?

GARY HART:

Or some version thereof. I think we have been lucky that in the 60 or 70 year history of the nuclear age that we haven’t come closer than we have to the use of nuclear weapons. I remember studying these issues in the ‘70s with [Republican] Barry Goldwater because there were false alarms about Soviet missiles headed for the United States. The strange [exact] number of missiles—222—caused the command structure to downgrade it. It turned out it was a $1.95 computer chip. Bill Perry [former deputy secretary], who knows more about accidental nuclear war than anyone, has long been terrified about this possibility.

I think we have been lucky that in the 60 or 70 year history of the nuclear age that we haven’t come closer than we have to the use of nuclear weapons.

JON:

You and Goldwater worked closely on defense issues. Hard to imagine nowadays.

GARY HART:

I’ll tell you an anecdote. I was reelected in 1980 when a dozen Democrats lost. No one ever went back and figured out how I did it. The Colorado Republican Party had its Lincoln Day dinner and Goldwater came in to give the keynote speech. The press met him at the airport and asked why he wanted to defeat Gary Hart. Barry was getting cranky and had finally had enough. He said, “Gary Hart is the most honest and most moral men I’ve ever met.” We had 250,000 copies of that story on the streets of Colorado the next day. Set and match.

JON:

The 9/11 anniversary reminded me that you and the late senator Warren Rudman predicted that something like that would happen. Could you walk me through that a bit?

GARY HART:

I do not claim total credit for the [Hart-Rudman] Commission but I did send a letter to President Clinton [in the mid-1990s] and urged him to do what Harry Truman did after the end of World War II—that is, appoint a group of senior experts, former military, intelligence, diplomats to think about the threats of the 21st Century and how they were different from the 20th. What is America’s role in the new postwar world? We issued our final bipartisan report on January 31, 2001 and were ordered to deliver the report physically to the President of the United States. George W. Bush would not receive us. Vice President Dick Cheney would not receive us.

Our report said, in effect, America will be attacked by terrorists using weapons of mass destruction, and Americans will die on American soil, possibly in large numbers. Nothing happened and eight months later, the attacks occurred. Now, people say, well, there wasn’t enough time to put together a response. Yes, there was time. The three components of homeland defense we identified—Customs, Border Patrol and Coast Guard—did not have a common data base and common communications system. But those steps could have been taken in those eight months. Would it have stopped the attacks? Who knows, but it would have given us a heck of a lot better chance.

JON:

At a press conference, you said an attack could be “imminent” and a senior Washington journalist walked out and muttered that you were an alarmist.

GARY HART:

True. I think we got a small page two story in the Washington Post, but it was all in the context of, well, here’s another commission warning about the future.

JON:

If the Bush Administration had even begun to implement your recommendations the odds are high they would have “connected the dots,” as analysts put it in the aftermath. The 9/11 Commission is clear on that. Clinton was much more focused on disrupting terror networks than Bush in his early days. Do you think if Al Gore had been elected in 2000, he would have taken action to prevent a 9/11-type attack?

GARY HART:

Yes. I think the foot-dragging on the part of the new Bush Administration had to do with one simple Republican belief: shrink government. The argument to be made—if officials had let us—was that 80 to 90 percent of what we were advocating for in the new Department of Homeland Security [we recommended] already existed. This was about consolidation, not creation.

JON:

Even if Gore hadn’t had time to set up a new department in eight months, he and his national security adviser—likely Leon Furth—would sure as hell have responded in the summer of 2001 to the CIA report headlined: “Bin Laden planning attacks inside the U.S.” Bush and Condi Rice ignored it.

Speaking of counterfactuals, how would the world have been different if you had been elected in 1988?

GARY HART:

After my ’84 run [where Hart almost beat Walter Mondale for the Democratic nomination], the polls showed me substantially ahead of [Vice President] George H.W. Bush. So red carpets were rolled out all over the world. I was invited to meet President Gorbachev and we spent four hours together.

I had in mind if I were elected in ’88 to invite Gorbachev to the inauguration. And then in the interim between the election and the inaugural to negotiate sweeping arms control agreements, trade agreements, citizen exchanges. I later asked Gorbachev how he would have reacted. He said, “I would have been there in a heartbeat.” So if you can imagine the inaugural, January of 1989, with the president of the Soviet Union on the reviewing stand. It would have changed the world.

I had in mind if I were elected in ’88 to invite Gorbachev to the inauguration…I later asked Gorbachev how he would have reacted. He said, “I would have been there in a heartbeat.”… It would have changed the world.

JON:

Speaking of that campaign, I’ve always assumed that because you got back in briefly in 1988 that you strongly regretted dropping out in 1987. But I’ve never asked you. [Virginia Governor] Ralph Northam showed recently that if you stick it out, the press eventually moves on.

GARY HART:

I had no choice. What I realized from the McGovern campaign is that if a campaign hits the wall, money dries up. I’m not going to go into this, but there is overwhelming evidence that the events in Miami [the party on the yacht named “Monkey Business”] were all a set up. And that’s from the horse’s mouth—Lee Atwater, among others.

The firestorm that happened in the spring of ’87 was the beginning of the changed relationship between the media and candidates. There had been an unspoken rule for a series of presidents—before office and in office—that unless it affects his ability to do his job, we’re not going to report it. Well, thanks to Rupert Murdoch and others, there was no way [to win]. I did get back in—to answer my children’s plea, that if you believe in yourself, you have no choice but to get back in. I knew the odds were against [me] and lo and behold, when I went up to New Hampshire and elsewhere, all the mob of reporters wanted to talk about was Miami.

“There had been an unspoken rule for a series of presidents—before office and in office—that unless it affects his ability to do his job, we’re not going to report it.”

JON:

I was covering media and politics then for Newsweek and I think that in ’87, if you had toughed it out, you would have had a second press conference about it, then a third and you’re right, your money would have dried up. But then polls would start to show—as they did later for Bill Clinton—that the people really didn’t give a shit about this. You would have lost your big lead but also touched bottom and be edging up again by the summer of 1987. You would have still had to answer questions about it, but could basically have said—as you did when you got back in—“Let the people decide.”

GARY HART:

I’m amazed that you [don’t] understand your industry. The story was so flimsy but they wouldn’t let it go. A network went to the newspaper [Miami Herald] and asked to interview them about how they got the story and they refused to talk. So you had a newspaper that refused to be honest.

JON:

I called the Herald in 1987 and they wouldn’t talk to me about it, either.

GARY HART:

Our phones were ringing from very dear friends—women—saying “I’m getting calls asking if Gary Hart ever hit on you.” This was very widespread. There was a desperate effort to confirm the original [story]. I had a person—a single woman—my family cared about who said, “If reporters come to my door and demand to interview me, I’m going to kill myself.”

JON:

Oh, my God.

GARY HART:

So there you are. Toughing it out was not an option.

JON:

What did think of the movie [The Front Runner], based on Matt Bai’s book, where Hugh Jackman played you?

GARY HART:

Well, the movie that was made was not the movie the director [Jason Reitman] told me he was going to make. He approached me before anyone was cast and said, “All my friends in Hollywood keep asking each other, ‘How did we get Donald Trump?’” And he said, “It finally dawned on me that—we got Donald Trump because of you. And that’s the story I want to tell.” And he didn’t say, “Will you cooperate.” They were going to do it anyway. They were going to draw a line from my experience in ’87 to the decline of politics, Clinton, all the rest of it.

JON:

Well, that would have been a very hard movie to make.

GARY HART:

I think it was a much more important year than people realize, not only because of my experience and the fundamental change it represented. A corner was turned in American politics, with the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine [which made uncontested rightwing radio possible] and Murdoch’s establishment of the Fox television network. [Fox News Channel would arrive in 1996].

“All my friends in Hollywood keep asking each other, ‘How did we get Donald Trump?’” And he said, “It finally dawned on me that—we got Donald Trump because of you. And that’s the story I want to tell.”

JON:

That makes a lot of sense. I’d never focused on that year before. With the feeding frenzy over your personal life, Fox, Limbaugh—1987 is when the old guardrails began to come down and the politics of personal destruction that is so important a part of Trumpism really began.

GARY HART:

I’d urge you to look at my statement at the end of my campaign in Denver. I said if we go down this path it will fundamentally change American politics—if journalists or anyone they hire are going through trash, peeking in windows—which is what the Florida newspaper did in my case. And the list goes on.

JON:

I pretty much broadly accept your indictment of my business. But I’m trying to puzzle through what I think is the bigger political story of the last 30 years, which is how the Republican Party got itself into a place where it could be hijacked by Donald Trump.

GARY HART:

I don’t disagree with what you’ve said at all. We all know how it happened, how the Republican Party went down the rabbit hole. How they’re going to get out—I don’t know. But Jonathan, 74 million Americans voted for Donald Trump.

JON:

It’s just mind-blowing.

GARY HART:

Steps are being taken at the state level, supported by Trump, to undermine democracy in America. It’s sinister. They haven’t backed off and they’re getting ready for ’22 and ’24. This is a hellish fight for the soul of American democracy.

Steps are being taken at the state level, supported by Trump, to undermine democracy in America. It’s sinister. They haven’t backed off and they’re getting ready for ’22 and ’24. This is a hellish fight for the soul of American democracy.

JON:

You went back to college—Oxford—to get a PhD when you were 63. Why did you decide to do that?

GARY HART:

When I left [Bethany Nazarene] college in Oklahoma, I studied philosophy and religion at Yale Divinity School and the graduate school and then transferred to the law school. But then the Kennedy campaign came along and “Ask what you can do for your country.” [More than 30 years later], I went back to school and finished a PhD.

JON:

What was your dissertation on?

GARY HART:

Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of the Republic. Founders did not use the language of democracy. For Adams and Hamilton, that word—“democracy”—scared them to death. It meant the French Revolution. So they all created a republic. But late in life, Jefferson, in correspondence with Adams, said we made a mistake in putting this country together because there is no arena for American citizens to participate, and the centerpiece of the republic is supposed to be civic virtue and citizen participation. So he advocated for what he called “ward republics.” Today we would call them local governments—county commissions, city councils. When Jefferson learned about the New England town meetings, he said, “That’s what I’m talking about.”

JON:

That remind me of where “Keep Our Republic” gets its name—the famous story of when Franklin left the Constitutional Convention one day and was asked by a woman what form of government they were creating and he answered, “A republic, my dear—if you can keep it.”

GARY HART:

The next 36 months are going to tell the future of America.

JON:

Thanks, Gary.