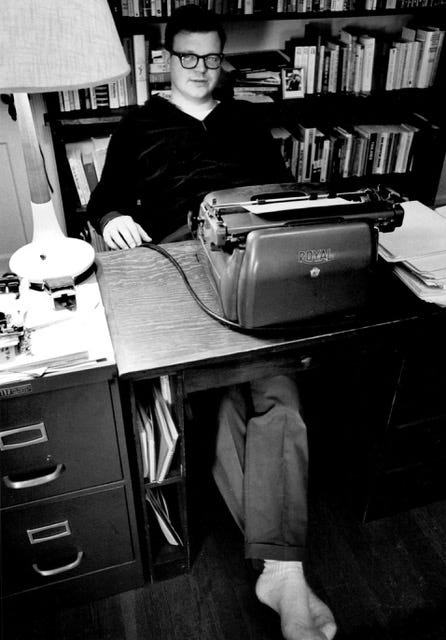

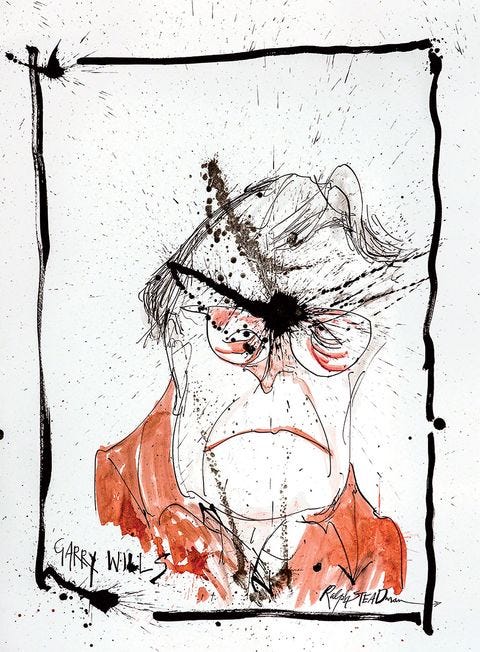

Ruminating with GARRY WILLS

On the Texas abortion case, why Ike was the best postwar president, and how his late wife made him smarter

I first met Garry Wills at one of the political conventions of the 1990s. I had long admired him from afar as one of America’s most brilliant public intellectuals and our (few) personal encounters solidified the impression.

Now 87, Garry grew up with a Protestant father and Catholic mother. His father was a philanderer and his mother raised him and his sister alone. He taught for decades at Northwestern University and has written more than 50 books, most of them about religion, politics, history and the classics. Originally a protege of William F. Buckley, Garry started moving left in the 1960s after turning against the Vietnam War. For many years, he wrote a thoughtful syndicated newspaper column and has written important pieces for the “New York Review of Books” and other publications. In 2019, his wife, Natalie, died after 60 years of marriage and three kids together. He still writes most days and is completing a book entitled “Living Through the Human Rights Revolution,” that chronicles the changing rights of women, Blacks, LGBTQ and others.

JON:

Hi, Garry.

I only met Natalie once, when I arrived one day at your house in Evanston before we went to lunch. Could you reflect briefly on the secret of a long marriage? Is it true that you met her when she was a flight attendant on your first flight on a plane in the late fifties?

GARRY WILLS:

The idea that it was my first plane ride was floated by Bill Buckley on the Charlie Rose Show and has lived a widespread life ever after -- I don't bother to refute so minor a matter. [In fact], my first plane ride (years earlier) was from St. Louis to Detroit, and memorable for me because the flamboyant Carl Sandburg was on the small commercial prop plane, and I was too awed to address him. I had read the first volume of his Lincoln bio in high school.

[Later], Natalie was a "stewardess" (terminology of the time). I have told that story, but not this part: She said, "You are too young to be reading that book” —The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (I was 23, so was she). I answered: How do you know? Have you read it? She said no, but that she had read a critique of it (by Walter Kaufmann, in her sociology class at Sweetbriar). When we met Kaufmann at a literary event in Acapulco, I told him, "You were our Galahaut," -- the go-between that Dante’s Paolo and Francesca were reading about when they fell in love. He liked the reference.

You ask about long marriages. All I can say about ours is that learning from each other kept things going. I got up every morning confident I would be smarter by nightfall because she was there.

“You ask about long marriages. All I can say about ours is that learning from each other kept things going. I got up every morning confident I would be smarter by nightfall because she was there.”

JON:

You remain a practicing Catholic but a skeptical one. Could you briefly explain your concept of “mater si, magistra no” and how it might be used to bolster today’s dwindling Catholic flock in the West?

GARRY WILLS:

I’m Catholic (mater) but not papalist (magistra). I agree with the Reformation that the papacy is a late-medieval invention [and addition] to the Christian tradition. Obvious question: Then why not join the Reformers? I already have. I rely on the passage in Luke 9.49-50, where Jesus's followers come back from their first mission and say they found someone casting out devils in his name and told the man to stop "because he was not one of us." Jesus says: Why tell them to stop? Anyone who is not against us is "one of us." All those acting in his name are "one of us."

The great scandal of historical Christianity is Protestants and Catholics persecuting and killing each other. When they are not doing that, I am a Catholic, a Lutheran, a Baptist, a Calvinist, and so on. Then why start with Catholic? It is the base I began from, and I cannot be opposed to it on the same grounds that I am not opposed to Lutherans, and other denominations.

JON:

You wrote a book about Pope Francis six years ago. You seem to really like him.

GARRY WILLS:

I agree with the friend who wrote me in surprise. "What on earth has happened? It looks like they have elected a Christian to the papacy!" Francis is the victim in a nest of vipers. As he knows. The irony is that John Paul II, who hated Jesuits, made him a bishop. That fanatical pope thought (with good reason) the Jesuits hated [Jorge] Bergoglio. [Later Francis]. The great Renaissance historian John O'Malley, S.J. told me John Paul could not believe Bergoglio was "a real Jesuit." Francis is trying to wriggle out from all the Vatican mufflers of his message, but he just keeps quoting Jesus at them. I love the fact that he chose his name not from a Jesuit saint (Francis Borgia, Francis Bellarmine) but from the saint of Assisi who was not even a priest. So much for the clericalists.

[Pope] Francis is trying to wriggle out from all the Vatican mufflers of his message, but he just keeps quoting Jesus at them.

JON:

I noticed that the National Review’s Kevin Williamson, in his attempted takedown of your recent pro-choice New York Times piece, makes no effort to refute your point that the Catholic Church has never suggested baptizing miscarried fetuses. This seems to me to be the dispositive argument in the entire Catholic debate over abortion. Am I missing something?

GARRY WILLS:

Kevin Williamson thought he refuted my claim that abortion is not in Scripture by citing "Thou shalt not kill." But foes of abortion are the first to say that commandment does not apply to cases of self-defense, war combat, or capital punishment. The Christian tradition was not interested in the fetus until recent times. That is fascinating. The Evangelicals were bitter foes of Catholics right up through the Klan days of Al Smith and J. T. Scopes. The evangelicals began to join Catholics on the abortion issue, helped along by people like Francis Schaeffer (A Christian Manifesto), Richard Neuhaus and Chuck Colson (Evangelicals and Catholics Together). A swarm of Catholics and Evangelicals were making marriages of political convenience. Many are listed in the recent Tom Edsall column.

JON:

Your reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision in the Texas abortion case—not just severely restricting abortion but empowering vigilantes?

GARRY WILLS:

This was the Supreme Court pretending to know the law as it dodged the Texas way of dodging Roe v. Wade by commissioning self-appointed prosecutors [vigilantes and bounty hunters] to do what the state wants done but is too cowardly to do itself ("riches for snitches").

JON:

You have returned again and again to studying and writing about Augustine. Why?

GARRY WILLS:

I liked him in high school because he was clever. He loved puns and paradox and original ways to approach old questions. When in school we had Thomas Aquinas force-fed to us, I learned to like Augustine even more. Thomas was a company man. Loved the rules, and made more and more of them. Of course, by his time the papacy exists and needed ever more clever excuses for it to be invented.

[By contrast], Augustine did not have a high regard for the Bishop of Rome. He didn't want to be a bishop himself, but was not given a choice. Part of his idiosyncrasy was that he is the only major thinker in Early Christianity who was monolingual. He loved learning Latin at home from family and loved ones, and hated having Greek ineffectually beat into him by strangers in a strange town. He loved the Latin bible -- and asked Jerome why he was upsetting people's memories of it by redoing it straight from the Greek.

Of course, he knew the Greek fathers got there first on things like the doctrine of the Trinity and that they knew things he didn't know. That made him cautious and humble and endlessly inventive. He worked from Paul's hymn saying we live by faith and hope and love -- but only for a while. Faith will give way to knowledge in heaven, and hope will give way to certainty, but love can never end.

He distrusted those Greek thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, who made the cosmic order a matter of the mind, of truth and justice. He knew truth and justice had their place, if they could keep it. But love trumped them. That is what trinitarianism meant to him. God needs company, the lover and the loved. Monotheism is the God of the Greeks. [Augustine] wants Trinitarianism, the union of mind, memory, and will that show God made man in his image.

JON:

You described yourself as a conservative in a 1979 book, long after you had moved left amid the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. Can you pinpoint a moment when American conservatism went bankrupt? Same question re the GOP.

GARRY WILLS:

In a way, this answer is a variant of the prior one. Modern liberalism builds on individualism, the rights of the individual, as discovered by separate minds, and administered by impersonal courts. All nice in theory But in fact we are more often united by shared goals, reached by compromise, and administered by pragmatic norms. [Old-fashioned conservatism.] I tried to work out something along these lines in an early essay I called "The Convenient State." [Edmund] Burke and [John Henry] Newman and Samuel Johnson beat me to it, of course. The danger of this [conservative] school is that it can resolve to mere tribalism. That is why it needs to be corrected by an open-mindedness that is the mark of community as opposed to the clan.

JON:

The death of the Roman republic is, not surprisingly, part of the conversation these days. What dimension of that story is most relevant?

GARRY WILLS:

Actually, I was more a Greek than Roman student, though the obvious ancestor to Trump's compulsive non-stop need of constant rallies was the Roman Circus. I find more scary now Aeschylus's warning in Agamemnon that the time of social collapse is the moment of overconfident victory. The nincompoop [Francis] Fukuyama thought that our victory in the Cold War would bring us an end of history, where our only problem would be the boredom that arises from lack of conflict. We should have been listening, in our celebration, to Cassandra. She told the Argives that sins of the Atreids were haunting them from long before their victory in Troy.

JON:

The first of your many books that caught my imagination was “Nixon Agonistes,” which was written before Watergate. As bad as that scandal was, the system eventually worked. What is the outlook for excising the cancer of Trumpism?

GARRY WILLS:

We don't deserve it. Why should we get it? Do we think we can celebrate a man so manifestly stupid and vicious as Trump and not have it cost us dearly? We have just begun to pay. Trump is not the problem. We are. How do we get rid of ourselves?

Do we think we can celebrate a man so manifestly stupid and vicious as Trump and not have it cost us dearly? We have just begun to pay. Trump is not the problem. We are.

JON:

Another of my favorite books is “Lincoln at Gettysburg.” For some reason, a Lincoln line after losing an election—a line I first heard as a kid from Congressman Sidney Yates— keeps coming to mind: “I feel like the boy who stubbed his toe in the dark: I’m too old to cry but it hurts too much to laugh.” I’d argue that concessions after elections are the essence of our republic. Do you agree?

GARRY WILLS:

I thought I heard that quoted by Adlai Stevenson. I doubt Lincoln said it. That is the trouble with being so quotable. You will be quoted -- Twain, Mencken, Dorothy Parker, Yogi Berra.

JON:

After my book about Obama’s first year as president was published in 2010, you dinged me—rightly, I must admit—for being too kind to Obama in my treatment of the futile surge in Afghanistan. Could you explain more broadly why you think Obama was such a disappointment?

GARRY WILLS:

I don't remember dinging you. I don't forgive myself if I did (though I hope you will). On Obama, I never knew him in Chicago, though I knew many who did. The first time I gave him serious thought was at the urging of Bob Silvers [editor of the New York Review of Books]. He liked to chase me down in Italy and assign me some large task -- once, it was to review the latest “Rabbit,” for which he sent all of the novels to our hotel in Rome, so Natalie and I read them on trains from town to town, and she put her unerring finger on Updike's misogyny.

This time, Bob called to see if I saw Obama's TV speech on Jeremiah Wright. Of course I hadn't. But he had one of his bright ideas (they really were bright) of comparing that speech with Lincoln's speech at the Cooper Union. He faxed both to me expecting me to fax back a comparison in two days or so. When I did, he liked his own idea so much that he planned to run my essay as an introduction to the texts of both speeches in a New York Review book. But the Obama campaign refused to grant rights to Obama's text. I supposed that the campaign was afraid that Obama was too boastfully comparing himself to Lincoln (he was, or nearly so). When I met him in the White House and asked if this was the real explanation, he said he could not remember even hearing about the matter.

I was there, along with six or so others who had written books about presidents. He invited us early in his first term to ask if we had any advice for him drawn from "our" presidents. I said Reagan was known for his great speeches, but was warned against overdoing it, or he would cheapen the events. Obama said he was giving some big speeches at the outset, to make clear his new approach, but would ease off soon. At the end of the meal, he said he would go around the table to let us slip in one last thing we wanted to mention. I said that he ran by saying the Afghanistan war was a good one that turned into a bad one with the swerve toward Iraq. Some of his people were still referring to Afghanistan as the good war. I said, "Don't go back in there, you can never make a nation out of that place." He said, he was not going to go back, and "I would always have an exit strategy."

But of course [General David] Petraeus came to him praising his magic surge in Iraq and saying he could serve it up again in Afghanistan. I suppose new presidents, who thought they would have a clean slate if they gained office, always have military, intelligence, and diplomatic people revealing old commitments, secret deals, and certain posts that "cannot be betrayed," and using lasting experience to make them back them up. One reason I think Eisenhower the best postwar president is that they could not pull that guff on him. When Obama sent the troops back in, I wrote [publicly] about his comment to me. When the others at that dinner were invited back to what was promised for a while to be a continuing conversation, I was not invited, and didn't expect to be.

I suppose new presidents, who thought they would have a clean slate if they gained office, always have military, intelligence, and diplomatic people revealing old commitments, secret deals, and certain posts that "cannot be betrayed," and using lasting experience to make them back them up.

My disappointment in him was not just personal. I think other Blacks were right to believe he did not use his breakthrough to push farther. I know he did not want to be the "angry black man" (which prompted his earlier successes by being omnidirectionally placatory), and it is true he could not show overt favoritism --for the same reason Kennedy could not uphold Catholic schools. But when some thought he could use his office to edge on the changes they thought justifiable, he answered something like, "I am the change." Getting elected was his contribution. Perhaps. But a minimal claim.

Enough. You are as hard a taskmaster as Bob Silvers.

JON:

But can’t hold a candle to him as an editor. Thanks, Garry.

This was wonderful. Wow

I recall the high regard I felt for Garry during the sweaty days of Vietnam, Nixon, and Watergate. Sadly, I had lost track of his piquant viewpoints and writings - until now. In this conversation, I adore his Pogo-like admonition "Trump is not the problem. We are."