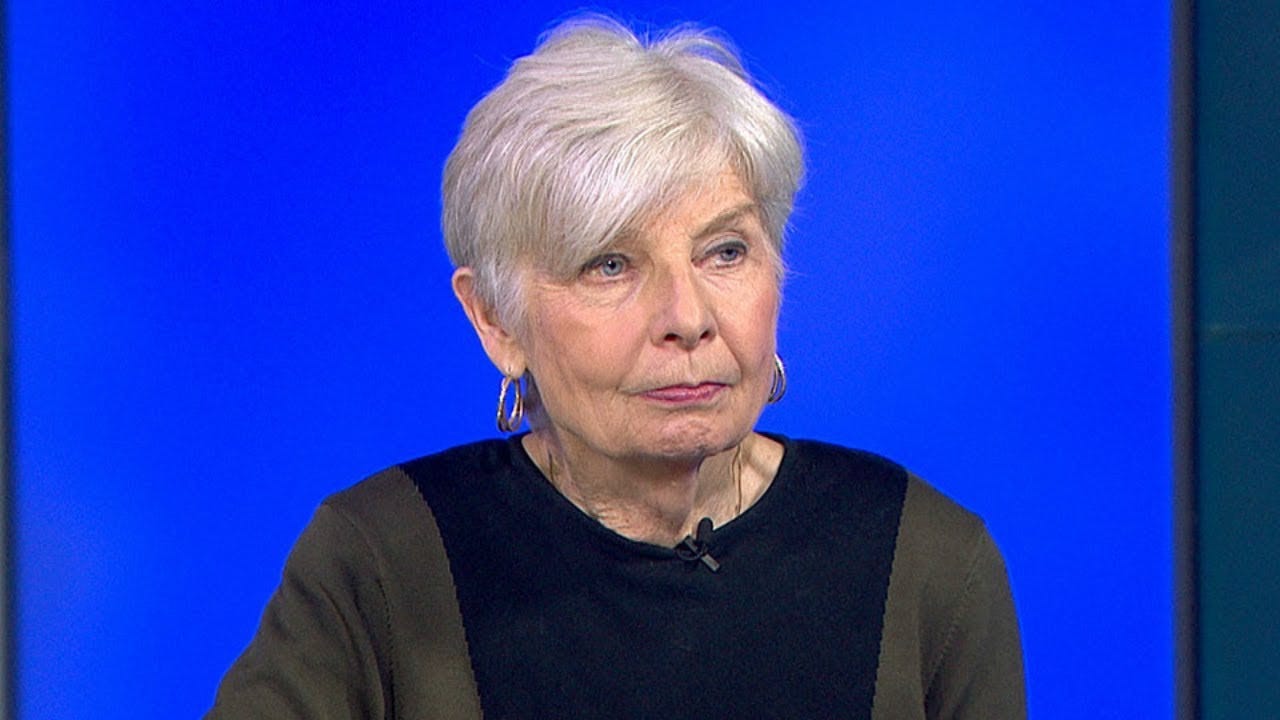

Ruminating with ELEANOR CLIFT

On the challenges to democracy and how the press covers presidents

I first met Eleanor Clift in 1983 when I joined “Newsweek.” She was in Washington and I was in New York but we worked together on many stories in the 28 years I worked at the magazine. Later, we became colleagues at the “Daily Beast,” where Eleanor, at age 81, continues to report and write fine pieces every week. Wherever she works, Eleanor is considered one of the nicest people around. But she is also a dogged reporter, incisive analyst and keen student of Washington, where she has worked for 45 years.

We cover a lot of ground here, from her early marriage to Montgomery Clift’s brother to the celebrity that came with being a regular for more than three decades on “The McLaughlin Group.”

JONATHAN ALTER:

Hi, Eleanor. Are you as worried as I am about the future of American democracy?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I am because I think the American people are disappointing me, though I don’t like to say that out loud. They seem attracted to authoritarianism, at least red America does. Trump people are carefully trying to replace election officials with people who would be willing to support alternative sets of electors if Trump runs and doesn't win in 2024. So I think it's very real.

JON:

I am concerned that the press is not adjusting to cover the challenge to democracy and it's still caught in a kind of an old paradigm on this.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Yes, I agree with that, and I am concerned about what’s called the “Green Lantern”theory of presidential leadership. A media narrative takes hold that suggests the president has superpowers and that if he doesn’t succeed with Congress on, say, voting rights, it means he isn’t trying hard enough.

JON:

That theory, originated by Professor Brendan Nyhan of Dartmouth, was first applied to Obama in 2013.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

And so if you apply it to Carter, I used what you said to me about his pardoning the draft evaders and not getting much credit for it.

JON:

Right. When Carter did something Gerald Ford didn’t have the guts to do even when he was a lame duck—bring closure to the Vietnam War by pardoning draft dodgers— some Democrats were disappointed that he hadn’t pardoned deserters, who were more often black and poor. Republicans don’t have this problem because they don’t care about legislation. Democrats, on the other hand, have a way of “making the perfect the enemy of the good,” as Obama liked to put it. We’ll see how progressives react if they lose the generous version of the child tax credit, which Manchin opposes. I sure hope the press doesn’t play that as a loss.

But my problem with the press right now in Washington goes deeper than that. I think holding Biden accountable is fine. Reporters have done that with presidents since the dawn of the Republic and it continues to be important. But it shouldn't be the master narrative of Washington politics. The master narrative should now be holding authoritarians accountable.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Yes, we have to do more of that.

JON:

On another press subject, do you think the media vetting process that existed in the 1980s and 1990s— where you and I and a relatively small number of other political journalists essentially decided who we were going to cover seriously (e.g. not Al Sharpton or Gary Bauer or others who never held public office)— would have stopped Trump if that process was still in place? What changed?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

The grievances that [Trump] was able to tap into. They were intense— this sense among a good portion of blue collar working America that the elites were looking down on them and they weren't getting their fair share. There was that [2004] book “What's the Matter with Kansas?” that explained how these grievances were more powerful than the actual economic circumstances. It created a sensation at the time because it showed the Democrats were not reaching the people who they thought were their base.

“…this sense among a good portion of blue collar working America that the elites were looking down on them and they weren't getting their fair share. …these grievances were more powerful than the actual economic circumstances. … Democrats were not reaching the people who they thought were their base.”

JON:

This isn’t new.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

If you go back to Clinton, Stanley Greenberg [Clinton’s pollster and the husband of Connecticut Rep, Rosa DeLauro] studied Macomb County, Michigan to better understand what were then called ”Reagan Democrats”. And before that, there were the “hard hats”—the construction workers who went for Nixon because he hated hippies.

JON:

Macomb County went for Obama but then it went back to Trump in 2016. The neighboring suburbs stayed Democratic. Given how horribly they do in rural areas, Democrats have to keep their gains in the suburbs or they’re in trouble.

JON:

Do you think that the politics of abortion will change if the Supreme Court basically overturns Roe next year? Will that end up advantaging the Democrats because they'll have to go out and and organize around it, or do you think that's wishful thinking?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I think the easy answer is to say yes, but I have two concerns. One is, are the Democrats going to figure out a way to really turn the unease about that decision into votes? Second, I think there's ambivalence about the viability question. If you move it from 24 to 15 weeks, I don't know that people would get all upset about that. What they're upset about is that [some states] are going to want a six week ban, which is unrealistic, and even try to prevent access in the early months.

“What they're upset about is that [some states] are going to want a six week ban, which is unrealistic, and even try to prevent access in the early months.”

JON:

So this chipping away is probably going to work for them?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I fear that. I would like to think that generations of women will turn out but I'm not completely convinced they will. I'm learning more about my country. You know, the revolution didn't happen in 2020. Bernie Sanders thought it would. Biden, it turns out, was the right choice and that's been a shock to people on the progressive side who really thought that they had the generational strength and the issues on their side.

JON:

How did you end up at Newsweek in the Sixties?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I dropped out of [Hofstra] after a year and I got a job in the city working for an ad agency on Wall Street and that's where I met Brooks Clift, who was 21 years older than me and coming out of his third marriage.

JON:

I had no idea he was that much older.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

This was actually a gift because he gave me books and took me seriously and what began as a platonic relationship turned into something else. I was 19 when I first met him and that was really my college education. Five years later, we married [in the brownstone of his brother, Montgomery Clift] and we had three children. And we did eventually divorce. He had a serious issue with alcohol. But when I look back and reflect on my life, it was he who took me on a different path than I would have been on if I had just stayed in the secretarial lane.

JON:

Was Montgomery Clift as troubled as we’ve heard?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I would recommend the recent documentary made by my youngest son, Robert.

It got excellent reviews, and he deals with his sexuality in a different light. In her book, Patricia Bosworth portrayed him as a tormented homosexual and that really wasn't the case.

JON:

In 2020, I was in a dinner group of biographers with Patty Bosworth and she was the first person I knew who died of Covid. I really liked Patty and I’m sorry to hear she got that wrong.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

He [Montgomery Clift] could be very charming. And the man that he was living with at the time and who was caring for him [after his famous 1957 car accident driving home from Elizabeth Taylor’s house] was his lover, Lorenzo James, who became a kind of uncle to my children and a real mentor to me. He passed away at age 92, about two years ago, but he was very helpful in my son's documentary.

JON:

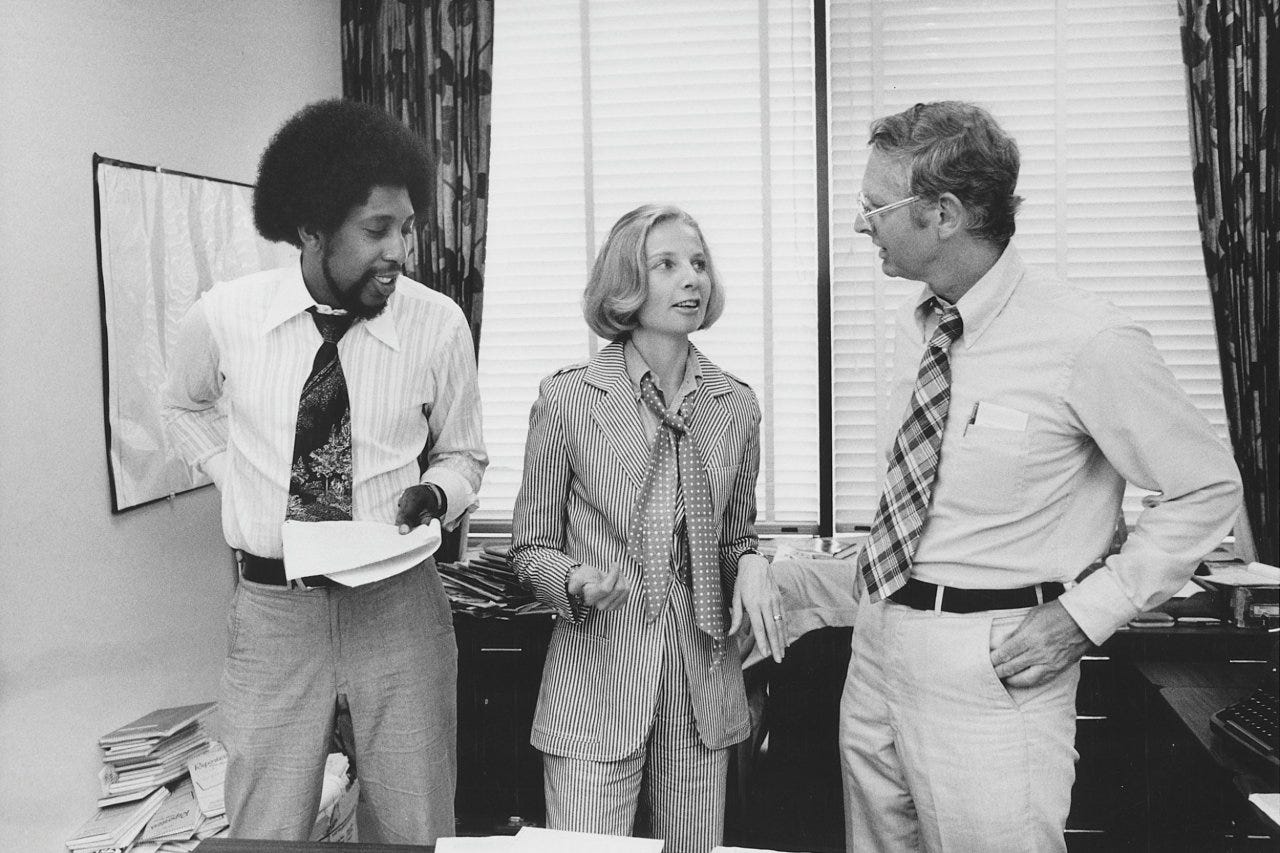

So you moved down to Atlanta in 1966 with your husband and because you had been working as a secretary and researcher at Newsweek in New York, you got the same kind of job in the Atlanta bureau. How did you become a reporter at a time when no women at Newsweek ever rose above the position of researcher?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

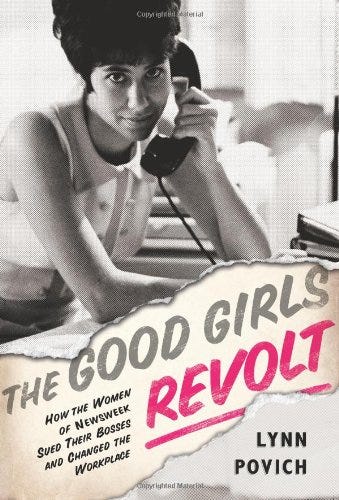

I was what was called a Girl Friday. But in this little bureau we covered seven states, and when Joe Cumming [the bureau chief] and two other male reporters were traveling, and these “roundups” [requests from Newsweek’s New York headquarters for help on feature stories] would come in and I couldn't always get a stringer [freelancer]. And so I kind of just did it myself. I didn’t really think there was that much to do about it. And then [in 1970] the women in New York organized to sue the magazine for gender discrimination. [Chronicled in Lynn Povich’s book].

I got a call from a woman who told me to stop doing reporting because I was being exploited. And it didn't make sense to me because I liked to be exploited—I didn't want to just be the secretary. So I didn't really follow that advice. But the women in New York got me a raise and and they put me on the launchpad to get a try-out as a reporter because part of the settlement was that the magazine would sponsor a certain number of internships for women to be writers and reporters. And so I kind of crept into Joe Cumming’s office and asked if I could get one of those internships, and Joe said fine, as long as you can get someone to sit at the reception desk, which was the only indispensable job there.

JON:

How did you begin covering civil rights leaders like Julian Bond and Andy Young?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Atlanta was called “the city too busy to hate” and some people have taken issue with that. But there was a lot of cross-pollination between liberals and African Americans and there was a luncheon forum where we would go eat soul food and listen to various speakers. And I think it was there I became friends with a woman named Xernona Clayton, who was a good friend of Mrs. King’s and when Dr. King was killed [in 1968], Xernona went with Mrs. King to Memphis and she then filled me in on a lot of details of the assassination.

Later, I interviewed George Wallace and what I remember most was that he was a really tough guy but was terrified of flying. We went somewhere in a little plane and Cornelia [Wallace’s wife] and I were chatting and he ordered us to stop speaking because we needed to control the plane, I guess.

JON:

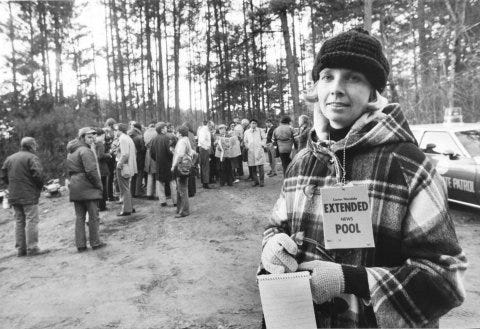

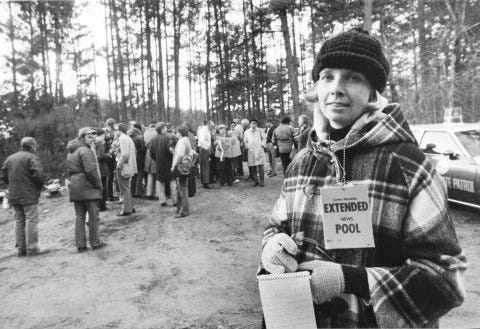

Your big break was the Carter campaign in 1976.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Mel Elfin [Newsweek’s Washington bureau chief] assumed there's no way this Georgia cracker is going to win. So why not assign the new kid on the block to cover it and I was right there in Atlanta. Maynard Parker [on his way to being Newsweek’s top editor] was my sponsor and he really believed in me, and he fended off the critics. I was so naive I didn't even know there were critics out there. I was just doing my job. And because I had the advantage of living in Atlanta it was easier for me to access the Carter characters like Stu Eizenstat and Jody Powell. My big coup was getting a proposal that Hamilton Jordan had written for Carter about how to become president.

JON:

You got that story? That's a famous memo. It lays out the whole strategy for winning the nomination. I read it in the Carter Library when I was working on my book.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Hamilton wouldn't give me a copy of it but he said you can take notes. And I had taken shorthand in high school so I furiously took as many notes as possible. And that became a cover story. The Time magazine reporter was not happy about it. He basically read the riot act to Hamilton and said that if you're going to give one newsmagazine a goodie, you have to give a compensatory goodie.

JON:

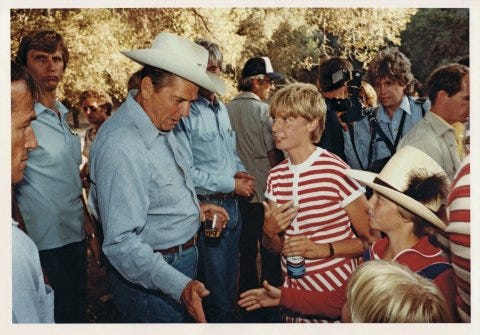

So you became a top Newsweek reporter in Washington and got pretty well known appearing [for 33 years] on The McLaughlin Group, where you never let the men get away with any of their shit. Was McLaughlin a jerk?

ELEANOR CLIFT:

Well, he was a former Jesuit priest and he was pontificating all the time. And that blowhard persona he had on television—he was very much like that in private. There were allegations against him by women. I never had any difficulties with him. I used to say that he would run hot and cold on people. And I was always kind of lukewarm.

I started in the early ‘80s when I hadn't done very much television beyond Washington Weekend in Review a couple of times. And he called me up and invited me to his office on K Street. And he asked me a series of questions, and I remember two of them. What did I think of Barney Clark's heart transplant? And the other one was, What did I think of arms sales to Taiwan? I looked at him and I said, “You know, I'm a reporter. I don't have strong opinions.” And he said if you want to be on my show, you better get some. You’ll be sitting across from Pat Buchanan or Bob Novak or whatever. I found getting strong opinions suddenly came rather easily. And so that's how that started. And it was really an iconic show.

“I looked at him and I said, ‘You know, I'm a reporter. I don't have strong opinions.’ And he said if you want to be on my show, you better get some. “

Today, it's just a very different world. I got a lot of grief from people who would say, “Why are you submitting yourself to that?” And I felt like, “Well, you know, if I'm not there then nobody's gonna to respond to them, make the fight. I enjoyed the give-and-take and occasionally I felt like I landed a good one.

JON:

You did, and your calm style gave you many victories, because you would make a point and it wasn't just persuasive on the substance. It was how you made the point. And when they’d go to commercial break, a hell of a lot of viewers would go, “I'm with Eleanor.” And it didn't feel to me like you had any problem standing up for yourself.

ELEANOR CLIFT:

I don't know where that came from. There was a time when I took a course on how to face an audience without taking a tranquilizer. And then years later, when somebody asked Joe Cumming [Newsweek Bureau Chief] about Eleanor, he said something to the effect that he couldn't believe this mousy secretary had gone on to this. I thought “Joe, I wished you’d used a different word than mousy.”

JON:

Thanks, Eleanor.

For over forty years I enjoyed endless and rarely repeated stories and recollections from Joe Cumming.

Every time he talked about Ms.Clift he spoke with a palpable admiration and respect. We all recognized and appreciate how much she has provided to help this nation grow in maturity.

Nice interview. I have never met Clift, but I had a good feeling about her as a person after reading your interview. Kudos to Newsweek for hiring her -- even if it took a lawsuit.