Ruminating with DON ROSE

The legendary Chicagoan on MLK,Jr. the infamous 1968 Democratic Convention and jazz greats he knew.

I don’t remember first meeting Don Rose but it was sometime when I was a kid. My late parents—Jim and Joanne Alter— were North Side “lakefront liberals” and they traveled in the same circles. Whenever I talk to Don now, I always think of two momentous years in Chicago: 1966 and 1968.

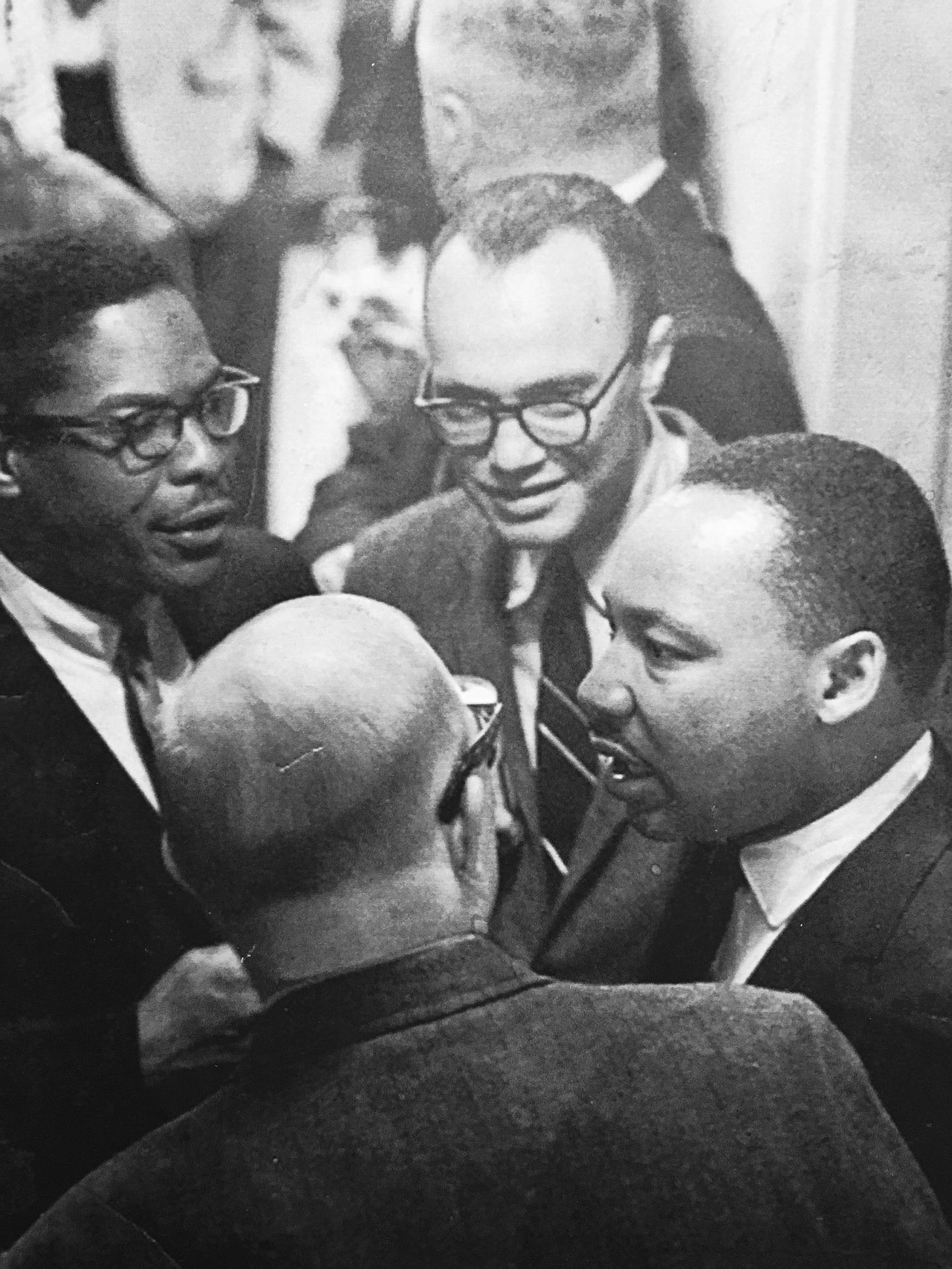

In the spring of 1966, I was eight-years-old and my parents hosted a small fundraiser for Dr. Martin Luther King, who was living in a Chicago slum to draw attention to poverty and racial injustice in the North. And I got a chance to meet MLK that night. Don was King’s press secretary for his Chicago Freedom Campaign and he ruminates below on this important if overlooked part of the civil rights movement.

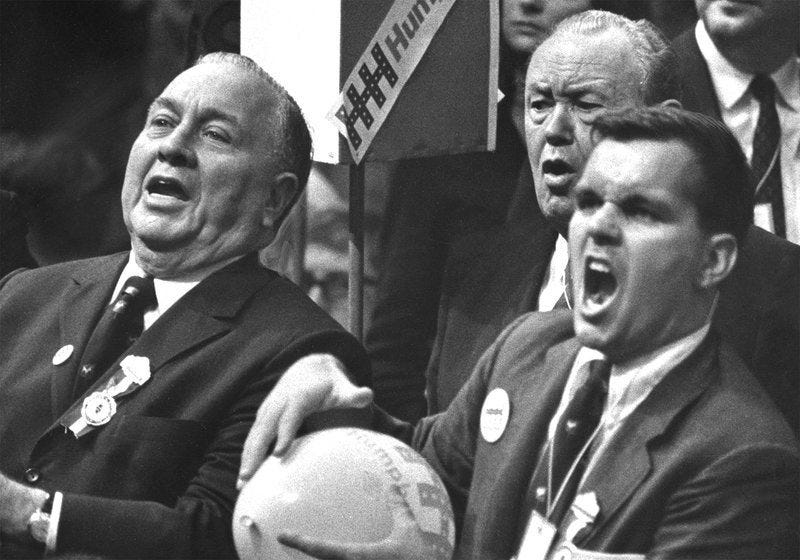

In 1968, the Democrats held their convention in Chicago. Inside the Conrad Hilton Hotel, my dad —whose 31 harrowing missions in a B-24 over Nazi Germany turned him against almost all wars—was working for the peace candidate, Gene McCarthy; my mom was working for Vice President Hubert Humphrey, the eventual nominee. (When they were spotted having breakfast in the hotel, a McCarthy aide accused dad of fraternizing with “a lady Humphrey operative.” My father replied, “that’s my wife!”).

I was just back from summer camp and running around the hotel, which mid-way through the convention was enveloped in violence. I still remember the shattered glass in the Haymarket Restaurant and the smell of stink bombs in the lobby. Mom grabbed my hand and we hurried to the parking lot and drove home through nervous National Guard troops. Nearby, Chicago police beat anti-war demonstrators in what was later called “a police riot.” The spokesman for the anti-war protestors was Don Rose, who coined the now-famous phrase, “The whole world is watching.”

For 60 years, Don—going strong at 91— has been the progressive conscience of Chicago. He’s a local legend as a journalist, political strategist and first-class jazz critic who knew Miles Davis, Max Roach, Charlie Parker and other jazz greats.

Don’s politics have long been at least slightly to the left of mine but I’ve concluded that he has been right on most things, including some of his criticism of Joanne Alter when she was an elected official in Cook County. The exception was when he briefly became a top aide to machine-hack-turned-fake-reformer Jane Byrne, mom’s arch-rival in politics and a nasty piece of work (in addition to being an abysmal mayor of Chicago). Over the years, Don has reliably thrown monkey wrenches into the Daley Machine and its successors and tutored David Axelrod and a whole generation of Chicago journalists and reform politicians.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Hi, Don and welcome to Old Goats. How alarmed are you about American democracy right now?

DON ROSE:

I’m very alarmed. People have talked about this, but the most devastating thing that's going on are proposals that would take the power away from the voters and turn it over to partisan legislators, or to judges, with the potential for reversing an election. If this has been tried some place at some time in American history, I'm unfamiliar with it. I think that's the most dangerous thing I've seen since World War II.

“I’m very alarmed…the most devastating thing that's going on are proposals that would take the power away from the voters and turn it over to partisan legislators, or to judges, with the potential for reversing an election. .. I think that's the most dangerous thing I've seen since World War II.”

JON:

Can we learn anything from your efforts fighting the Daley Machine?

DON ROSE:

The authoritarian Daley Machine thrived on patronage, racism, and election fraud. It was defeated by a combination of lawsuits and citizen organizing that exposed inequities and offered alternatives. The principles of fighting authoritarianism haven't changed and the struggle continues. That's an oversimplified answer, but also a guide.

JON:

What else should we do today?

DON ROSE:

Once again, an oversimplified answer is keep exposing the racism and do everything to organize around it as was done in the Georgia 2021 senate runoffs. Put the blame for inflation where it belongs—corporate greed, a Republican fault, which can be demonstrated by the rising markets and increased corporate profits in the face of otherwise financially crippling effects of the pandemic. Begin selling the benefits of the positive legislation the Biden Administration has already passed and put it in direct terms to people where they are--hardly an original thought here, but it must be executed by joining moderate and progressive Dems with clearer messaging. Biden must also take some dramatic action on inflation such as finally dropping the Trump tariffs. It will have a small but tangible effect if done quickly and put Biden once again on the people's side, not the corporatists.

[By the way], the progressives made a great mistake in denigrating the infrastructure bill as just kind of a throwaway compared to Build Back Better. By itself under almost any other administration it could be the tip of the spear and a cause for re-election.

“…the progressives made a great mistake in denigrating the infrastructure bill as just kind of a throwaway compared to Build Back Better. By itself under almost any other administration it could be the tip of the spear and a cause for re-election.”

JON:

We agree that we should be focusing more on voter subversion—overturning the will of the people—than voter suppression.

DON ROSE:

It shocked me far more than the voter suppression, which is— it’s not popular to say this— a rollback of expanded rights, not preventing people from voting.

JON:

Right. For most of our lives, we couldn't vote on Sunday, so shorter Sunday hours and restrictions on lock boxes and mail in voting are terrible but not as dire a threat to democracy as using state legislatures to overturn the will of the people. Unfortunately we have to depend on the Supreme Court to stop that menace.

DON ROSE:

Exactly. Nobody has been denied “the right to vote,” but that's a part of the rhetoric, so I'll probably be condemned for bringing that up.

JON:

You have the Bernie-style street cred to speak truth to progressives. Any other examples?

DON ROSE:

I think some have gone overboard on the issue of what is [wrongful] cultural appropriation and what is in effect a traditional absorption of other cultures into our culture. Why should that little girl who bought a Chinese dress suffer because she admired the work of others? We admire it when people appropriate styles from the French.

JON:

How did you happen to become the press secretary for Martin Luther King’s Chicago Freedom Campaign?

DON ROSE:

I was very heavily involved in the civil rights movement of the early ‘60s in Chicago and did organizing for the March on Washington in 1963, and the school boycotts of ’63 and ’64. And then word came out that King wanted to open up a Northern front. He originally was thinking about Harlem and he was looking at Chicago, Cleveland, maybe Detroit. And we put together a three or four day weekend of meetings, rallies and fundraisers, all around the city, and even into the suburbs, which impressed him with its organization. And it turned out we were the best organized city he visited.

When he went to a city or state, he would merge his SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) into the local civil rights organization or federation. That’s how [they got] the Mississippi Freedom Movement and [eventually] this became the Chicago Freedom Movement. [The Chicago group was headed by Al Raby].

JON:

In 1966, King and his family lived in a dilapidated apartment on the West Side of Chicago—long since demolished— to draw attention to slum conditions. Did you visit him there?

DON ROSE:

I did. It was a very standard Chicago apartment with a short hallway. I don't remember much about the decor. It was rundown and somewhat dirty and so on. I saw it before the landlord found out that King was gonna be living there, and he sent people in and cleaned it up and repainted some places and made it look more presentable.

JON:

What was your role?

DON ROSE:

My job was to tell him about Chicago politics and how to plan for meetings at such and such a place, give tips on what's happening in neighborhoods so that he can adjust his speeches to where he was going. He would give me a lot of his standard speeches but he would always have me to do a little preamble to localize it.

JON:

Was it your idea for him to march in Gage Park and Marquette Park [white neighborhoods on the southwest side, later the site of Nazi marches, where the vicious reaction to MLK became a national symbol of racism in the North]?

DON ROSE:

What led up to it was my idea. The group was interested in open housing, and we had a program of sending white people on real estate tours to borderline neighborhoods. Of course the white couple would be shown a white apartment, then a Black couple goes on the same tour and they're shown a Black area. And another white couple goes in and they're shown a white place again. And we would report that to the city's commission in charge of enforcing [anti-discrimination] and they never did anything. So we decided to hold a vigil in front of a real estate agency in Marquette Park.

We had an [interracial] group of maybe 20 or 30 people standing around in the evening and a crowd gathered around it. The white crowd was very hostile and things were looking potentially very volatile. King and Raby were not at this demonstration. Jesse [Jackson]and [James] Bevel were in charge of it, and the cops came and they offered to take us back to our headquarters before things got violent. Jesse and Jimmy agreed and we were all hauled off in the paddy wagon to the cheers and applause of the white crowd.

I and a lot of other people were very pissed that they [Jackson and Bevel] agreed to do this, rather than for the cops to be dealing with the hostile white crowd. The cops didn't try to disperse it or anything like that. So we got back to the headquarters and Raby was furious that they had done this. There was a lot of tension at times between Raby and Jesse. Anyway, everyone said, “Well, what are we going to do now?”

So we planned another open housing march and indeed the cops did protect us along the way [this time] because Daley realized that the cops were very bad at this first march. It was actually during our third open housing march that King was hit by a brick.

JON:

There were 4,000 people there, many with Confederate flags, hissing, shouting crude epithets, throwing stuff. How far away from him were you when that happened?

DON ROSE:

I was maybe 10, 12 feet away. I didn’t see that coming but I saw him go down. He got up and he had a sore head but there wasn't an open wound or anything. So we marched on to the real estate agency and held the vigil that we originally came for.

JON:

King said at the rally that “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the south, and I can say that I have never seen—even in Mississippi and Alabama—mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen in Chicago.” How did the whole campaign end up?

DON ROSE:

He [Daley] was excellent at defusing and deflecting things. He never said a harsh word to Dr. King. It was very Buddhistic all the way and that confounded King. He was expecting the response of a Bull Connor and he got the response of a Buddha, though [Daley] never did much of anything to address the demands.

JON:

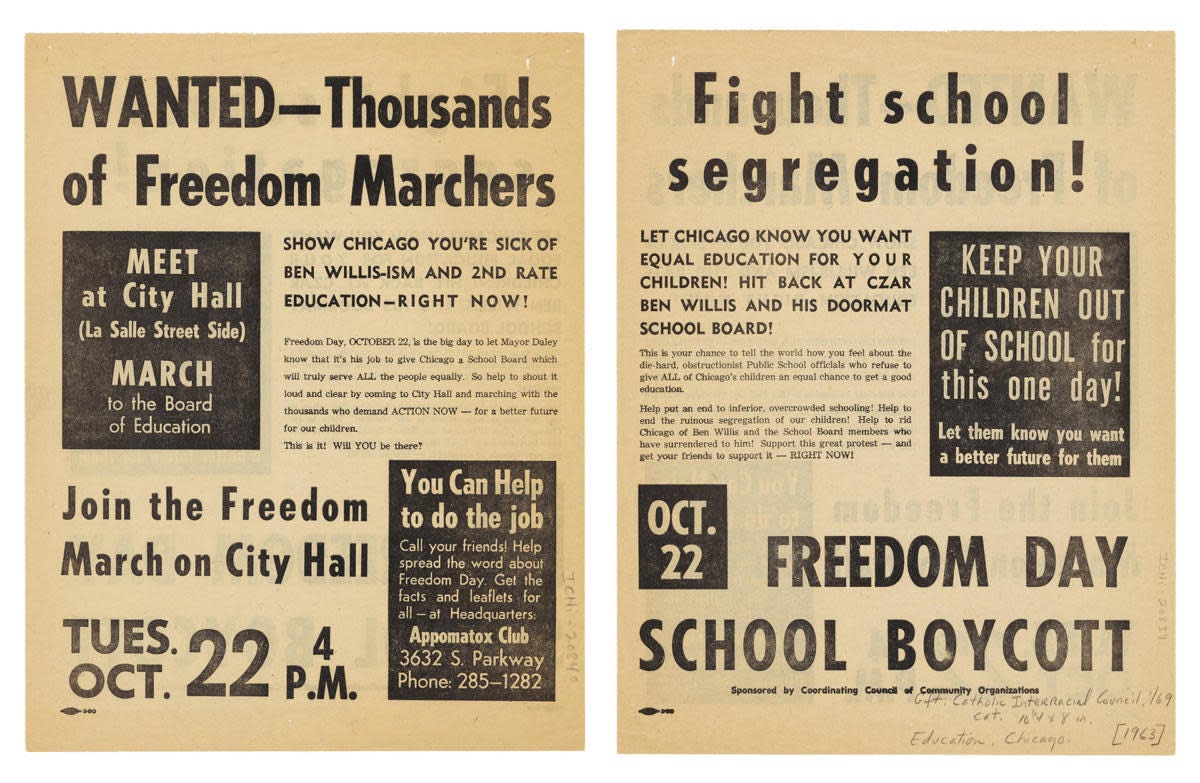

You were also very involved in the decision to boycott the schools. I think a modern reader might go “Yeah, I know the schools were segregated and that was really bad but was it better to have them not be at school at all?”

DON ROSE:

When we were organizing the school boycott, which was called Freedom Day, it was gonna be just one day out of school and that is not going to harm anybody's education. The first boycott was so successful that it got attention around the country, and we had people coming in from a dozen or so different cities to form a national school boycott group.

JON:

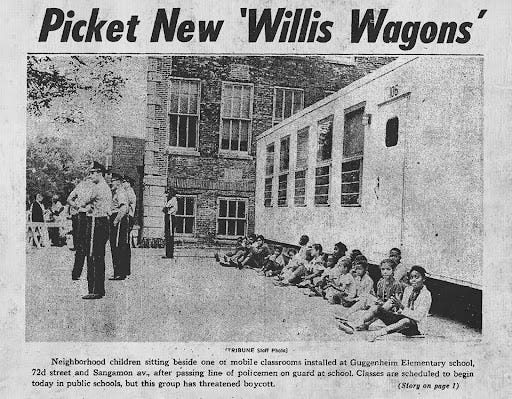

So if you had looked forward half a century, would you have thought that we should be doing better than we are on education?

DON ROSE:

I was optimistic. We thought we would get things done, and we would finally get rid of Ben Willis [Daley’s awful superintendent of schools, who was famous for “Willis Wagons”—trailers as classrooms for Black children in overcrowded schools].

We did that, but of course there were many other problems in Chicago that were more deeply ingrained. So we had civil rights actions on many fronts, and the King movement tried to attack on all of them—open housing, schools, health care and an economic agenda. Jesse Jackson was appointed the head of “Operation Breadbasket” [later, Operation PUSH], which King had originally helped organize in Cleveland. That was the economic arm that picketed food chains to hire more Black employees. And it was fairly successful.

JON:

What was the longterm impact of all of this?

DON ROSE:

The main thing is that it marked a major step in the political history of Chicago by beginning to liberate the Black community, which had been deeply divided. Before that, the Black community had a lot of machine-oriented public officials. The six Black alderman [on the Chicago City Council] were known as the Silent Six.

So we accomplished breakthroughs that brought more African-Americans into public life. The greatest failure was to improve the school system, which became more and more segregated. At the time, it was something like 51 percent white, 49 percent Black. [Today, it’s 11 percent white, 37 per cent Black, 47 percent Latino and 4 percent Asian]. We were looking for ways to integrate it but that never happened and we just had continual white flight—to the suburbs, private schools, Catholic schools, whatever. We’re still feeling the results of that now.

On the other hand, you look at Chicago today, and we have a Black female lesbian mayor [Lori Lightfoot], a Black woman in charge of the Cook County board, a Black woman lieutenant governor, and a half a dozen other major offices that are run by Black people. So, we've had that kind of success, but we still have the greater failures of not having the economic development and integration that's necessary to turn the city around.

We might have been able to do a better job if Harold [Washington] had not died so young [at age 65 in 1987]. If he'd had another term or two we may have been able to start the long term, sociological turnaround that was necessary. The fact that we waited so long to get our second Black [elected] mayor reflects the ongoing product of racism and improper behavior and segregation of Chicago in the first place.

JON:

Let’s talk about your jazz friends at the dawn of the Bebop era in the late 1940s and let's start with Charlie “Bird” Parker.

DON ROSE:

I got to know him when I was 17 or 18 years old and we became very friendly. I was playing [trumpet] in those days, not very well, but my career was shut off by an accident where I banged up my lips too badly to continue. So I often say if I hadn't had that accident, I might be a drunk or junkie by this point. My two best-known friends were Charlie Parker and Stan Getz.

JON:

Remind me of why Stan Getz was important.

DON ROSE:

Stan Getz was known for a lot of crossover [jazz]. The bossa nova stuff went from straight-ahead jazz and introduced a Latin element into it, and that popularized it. He was one of the great instrumentalists of all time, and was the epitome of the Lester Young school of sax, which faded away in the later Bebop era when it was overtaken by tenor saxophones. Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane pretty much obliterated the rest of the Lester Young school. Coltrane moved into free jazz, which takes you totally away from that [Getz] sound, and in the absence of chord patterns and so on.

JON:

Did you know Coltrane, too?

DON ROSE:

When I was around Miles Davis—that’s when I knew Coltrane, but we never hung out.

JON:

And how about Max Roach?

DON ROSE:

Max Roach [drummer] and I were very close. I met him at the same time that I met Bird [Charlie Parker] at the same club, the Argyle Lounge, which was at Argyle and Sheridan [Road] back in the old days. This was ’47 and ’48.

JON:

Wow, a club on the far North Side. I always think of the jazz clubs as being on the South Side.

DON ROSE:

This music was very new at that time, and the audience consisted of tons of Chicago musicians who were learning that new music back in the early days of Bebop.

JON:

How does this white guy get in with Max Roach and all these [Black] guys?

DON ROSE:

I call it “The bathroom where it happened.” I would say that 70 percent of the people who came to that club to hear Bird were white people, some of whom wouldn’t go to the South Side. Anyway, this was 1947, the first time Charlie played Chicago and he was at that time looked upon as a God by many people.

Miles [Davis] was playing but I had to go to the john. So I'm standing in the john and Bird comes in and takes the urinal next to me. And suddenly, we hear Max Roach’s solo. And he looked at me and said “Max”. That “Max” was the first word that Charlie Parker ever said to me. From then on, he was always very kind to me, which was something not often said about him. Miles thought he was a bastard and called him that publicly a couple of times. My son’s name is Max and he turned out to be a tenor player rather than a drummer.

Actually there's another less happy episode with Bird in that period that became a national shame. He was drunk and high and everything else, and he pissed in a phone booth in that club. That was one of the legendary Charlie Parker stories for many years.

JON:

How would you describe what they were like? Were they detached and a little distant? Were they just cool in a way that was at that time defining what cool meant?

DON ROSE:

I would have to say they were erratic. Remember these guys are all pretty difficult. They were all junkies, except [Dizzy] Gillespie for some reason.

I met Dizzy several times, but we never connected. I think there was something about me he didn't like. It may have been because I was buddies with Fats Navarro, who was a very unsung great trumpet player and often looked upon as a rival to Dizzy and Miles.

Knowing Bird and Getz, sometimes they could be just warm buddies talking about art, about books, about other musicians, usually with very kind words for them. You didn’t see a lot of jealousy. Then other times, they were either under the influence or needing drugs, and they could be distant and apart. So it's a very complex thing. If you've ever known any addicts, you would understand the variation from time to time. And these weren’t people that I would see every day. There might be six months or a year between visits.

JON:

Two decades later, you were press secretary for the MOBE—the National Mobilization Committee to End the Vietnam War. You coined the chant, “The whole world is watching” after protesters were first assaulted by the Chicago police. How did that happen?

DON ROSE:

The next morning, we held a press conference to show some of the people with their wounds and bandages and Rennie Davis [later a defendant in the Chicago Seven case] says, “What do we say?” I said, “Tell them they won't get away with it again because the whole world's watching.”

He used that to my surprise and it became the slogan. I wasn’t trying to try to phrase-make. There have been times I've tried to phrase-make but never been successful.

JON:

Were you on Michigan Avenue a couple nights later when it got really crazy. What was that like?

DON ROSE:

Just impossible to describe. We've seen the film over and over again through the years, but it doesn’t fully convey it. When we came over the bridge out of [Grant Park] because we were denied the right to march to the the convention [hall], we were tear-gassed and people were being beaten and thrown around. It was just stunning. I had never in my life seen that kind of violence perpetrated by anybody.

JON:

What did you think of Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago Seven?

DON ROSE:

I would say that hardly any of the characterizations, outside of Abbie Hoffman, were very accurate. Things were shown in the courtroom that didn't happen. Dave Dellinger did not punch out the cop who was tormenting him. And when they’re reading the names at the end—that never happened.

JON:

And Fred Hampton didn't show up in the courtroom, right? [After Hampton was murdered in his bed later in 1969 by police operating at the direction of State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan, Rose managed the campaign of the liberal Republican, Bernard Carey, who unseated Hanrahan].

DON ROSE:

Fred Hampton never showed up in the courtroom. And, actually, from the times I was in the courtroom, which was frequent, the judge [Julius Hoffman] was not nearly as nasty and bizarre in the movie as he really was.

JON:

My grandfather knew Judge Hoffman, and he was a much bigger asshole than Frank Langella played him.

DON ROSE:

But my bottom line is that [the movie] tells the moral truth of what it was all about. [J. Edgar] Hoover victimized [the defendants]. The whole thing was a set-up. It [the case] should never have happened in the first place, and I think that comes through pretty clearly.

JON:

Agreed. And I think Tom Hayden’s book Reunion is one of the best books I’ve ever read about the 1960s. But when you think back to that period—and when you see everything that communism did to human beings over the course of the 20th century—do you think in retrospect the American left was a little credulous, a little naive? I know the right wing has tried to smear you on this because of your influence on David Axelrod.

DON ROSE:

I was never a communist but I was in the Socialist Party led by Norman Thomas and Michael Harrington , which later became the DSA (Democratic Socialists of America).

There's an interesting parallel to some of these people who learned through the years about the villianies of Stalinism, and some of Leninism. Many peeled away after the show trials and various episodes, but others stayed with it. It’s kind of like what happens to some of these people who became Trumpsters. Once they decided they were for Trump, they stuck with him. Over the years, as they saw one or another ridiculous move by Trump, they somehow found a way of forgiving it. I would draw a parallel between that psychology and what was going on with many people on the American left with communism.

But I’ve never been afraid to associate with anyone. My partner on my newspaper [decades ago] was David Cantor, who was raised partially in Soviet Russia, and was in fact a communist. He used to tell me, “You know, we never actually had cards.” So, over the years I've worked on and off with everyone from liberal Republicans to communists.

JON:

Finally, thinking about the horrible crime rate in Chicago today. If you were to advise [Mayor] Lori Lightfoot and Governor J.B. Pritzker, is there anything on the horizon that— if it was properly implemented— could deal with this?

DON ROSE:

The best idea I've heard is to go after ammunition. By making it hard to get ammunition, you circumvent the question of taking away guns, and it may be constitutional.

JON:

Yeah, that's what Pat Moynihan wanted to do. We should try it.

Thanks, Don.

Great read, Jon, and what a fascinating man with such a rich history. Your own personal anecdote(s) as a child in Chicago whose parents were so socially conscious and involved in the 60’s is such a unique and interesting perspective on events seared into MY memory (as a fellow youngster during those turbulent times).

Great interview...good to hear both of your thoughts. Here is to hoping that the lessons learned from the past will somehow impact the new leaders coming up...