Ruminating with CASEY DINGES

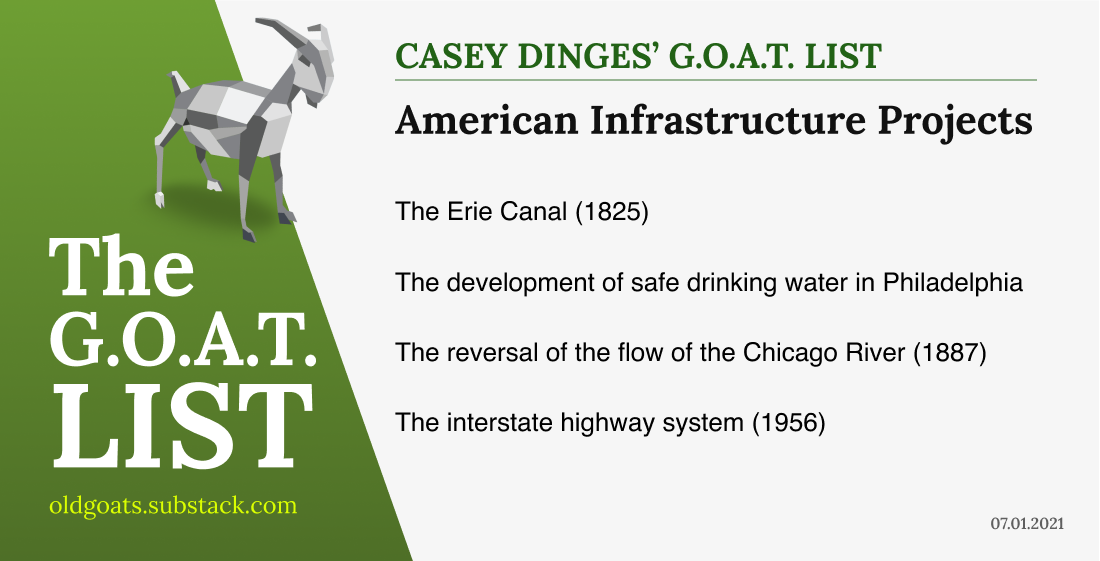

Insights into the Florida building collapse, why infrastructure is getting sexy, and the pain of growing up an orphan.

Casey Dinges and I have been friends since we were in kindergarten at the Francis W. Parker School in Chicago in the early 1960s. Starting at age ten, we attended many Cubs games together and because Wrigley Field had no lights then, we went to day games unaccompanied by adults and were taught many facts of life by “the Bleacher Bums” of Chicago lore. Once, with Casey by my side, I interfered in play and helped the Cubs win a game.

When we were nine, Casey’s father died, and when we were eleven, his mother died, leaving him and his brother, Barnaby, to be raised by another Parker family. Casey’s mother had fled the Nazis, which along with the Vietnam War and Watergate and everything else going on when we were kids gave him an interest in public affairs. So after graduating from Wesleyan, he moved to Washington and got a job as a lobbyist at the American Society of Civil Engineers, and rose over nearly four decades to the position of Senior Managing Director. He will retire this year with a legacy of having done as much as anyone to draw attention to the country’s woeful investment in infrastructure.

JON:

Hi, Casey.

Do you think lobbyists like you get a bad rap?

CASEY DINGES:

Yeah, a little bit. When people rag on lobbyists I like them to look at the rich language of the First Amendment, which includes the right to “petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

JON:

I think there are good lobbyists, who work in what used to be called “the public interest”—and that would include you, especially since you are lobbying for safety, technology, knowledge and broad investment, not specific projects—and bad lobbyists, who represent wealthy private interests looking for an edge. The latter are the ones FDR called “parasites.”

CASEY DINGES:

A little harsh. And we’re a professional organization, not a trade organization.

JON:

When you started issuing quadrennial “Report Cards” with all those Cs and Ds, it eventually got Washington’s attention. “Infrastructure” has now gone from an “I fall asleep” word to something almost kinda sexy. It’s now being used for broadband, child care, education, and even voting equipment, which is rightly defined by the Department of Homeland Security as “critical infrastructure.”

CASEY DINGES:

And President Biden takes it really seriously and personally. He actually timed his biggest speech [of the month] to the 65th anniversary of the Interstate Highway Act. And he weaves all kinds of history—including his personal history—into it, like what his father used to say to him, his relationship with senators, even how his wife and daughter were killed [in 1972] at an intersection.

JON:

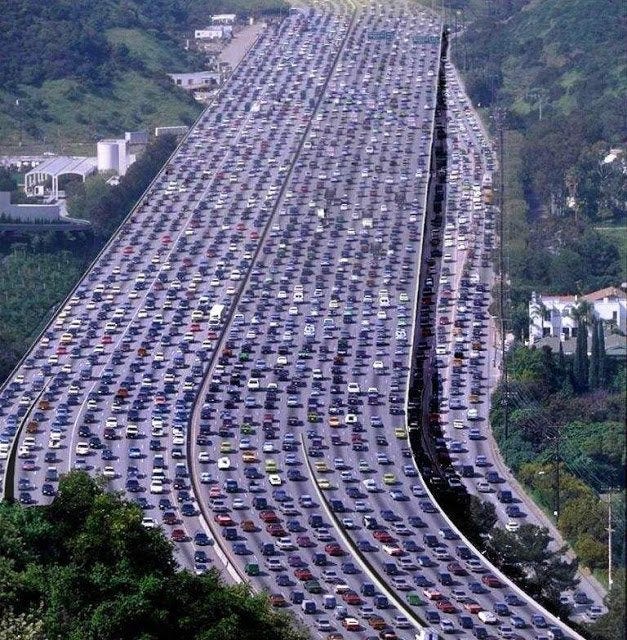

The interstate highway system is a huge deal we take for granted. It created tens of millions of jobs.

CASEY DINGES:

Neil Armstrong said the only thing wrong with the system is that it doesn’t extend all the way around the world. It transformed the landscape of the American economy—the auto industry, the hotel industry, the trucking industry. It comprises only four percent of the roadway miles in this country, yet it carries half of the traffic and 80 percent of the truck traffic.

Neil Armstrong said the only thing wrong with the system is that it doesn’t extend all the way around the world.

And Colin Powell said that it hastened the nation’s understanding of the civil rights situation. You could just get around much more easily and see what was going on.

JON:

All true, but in retrospect it would have been better for climate and better overall if we had more of a European rail system.

CASEY DINGES:

Yeah, we’ve gone car and airplane. but there’s two stories here. We have a freight rail system that works pretty well. But passenger rail doesn’t do well.

The question is whether there’s a complement to the highway system that gets people in and out of work, however many days a week they have to be in the office [post-Covid].

JON:

Traffic jams should be a thing of the past, right? Rush hour now is just stupid. There’s simply no reason for everyone to have to be there at 9 o’clock given what we’ve just been through without productivity loss.

CASEY DINGES:

It certainly won’t be the way it was before but how different it’s going to be is still a question.

JON:

You started doing these Report Cards in the ‘90s and they got very influential and Obama started talking about infrastructure and the ASCE Report Cards, but there weren’t enough “shovel-ready” projects in 2009 and the priority was getting money into the economy as fast as possible.

CASEY DINGES:

It was kind of a missed opportunity. He was trying to create jobs but a lot of [the $850 billion] was tax cuts and transfer payments back to the states so they wouldn’t have to fire everybody. So even though Obama highlighted the issue and proposed high speed rail—and got political pushback from some governors—it was fairly modest overall. Biden says he’s learned some lessons from that.

And he feels like the country needs to pull together on something—it’s bigger than infrastructure now.

JON:

I always thought “Infrastructure” was such a bloodless word and no one knew what it meant.

CASEY DINGES:

Actually, we were a little surprised to find out that even in the early ‘90s the public had a much better understanding of the kind of traditional definition of infrastructure than my own members really appreciated or gave them credit for. They can even tell you who the big contractors or engineering firms were in their districts.

JON:

So why has it taken so long to make basic capital and maintenance investments in the country?

CASEY DINGES:

Good question. I thought for sure when the Minneapolis bridge went down in 2007 that we had a moment there, but we couldn’t even get a vote on the House floor.

JON:

I think it was partly the demise of earmarks, which go back to the 18th Century as a way to get things done in our political system. It used to be called pork—stuff for the district that could be used to grease the legislative gears. I understand why John McCain was upset by Alaska’s “Bridge to Nowhere” but it went too far.

CASEY DINGES:

More people knew about the Bridge to Nowhere than the collapse of the Minneapolis bridge. But earmarks were a sideshow. If you’re really ahead of the game and planning stuff properly, earmarks aren’t necessary because you’re not playing catch up.

JON:

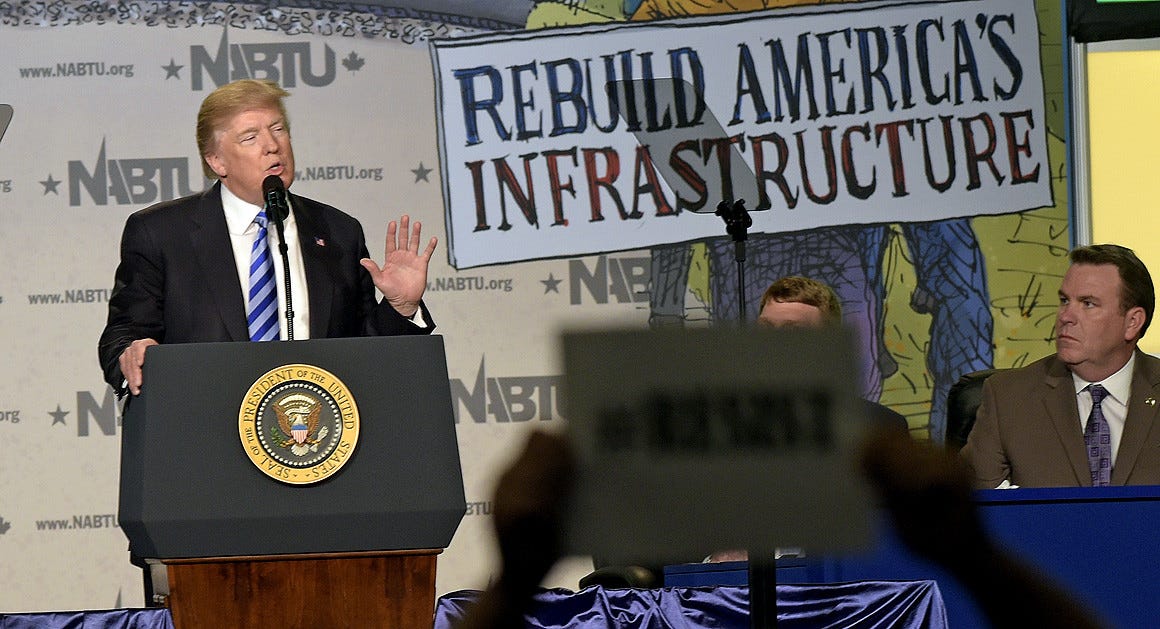

In the last 40 years you had an assault on the whole idea of government. You had people in the Republican Party who were just philosophically opposed to investing in the United States.

Trump in his first two years had a Republican Congress, he’s a builder by background, he has four or five initiatives called “Infrastructure Week”— and yet nothing happened. That’s because Mitch McConnell doesn’t give a shit about infrastructure even though there’s a major bridge in his state that’s falling down. But that was then. The press doesn’t realize it, but he’s not in charge now and the Democrats have the power to ram it down his throat if necessary.

CASEY DINGES:

Biden feels strongly about bipartisanship and will likely stick to his guns [and not do physical infrastructure through budget reconciliation]. Now we have what you might call Infrastructure Summer and a real chance not to solve the problem but take a significant step in the right direction. Of course, neither Biden nor the Republicans want a gas tax hike, though we haven’t had one since Clinton was brave enough to do it. Biden is looking out for the little guy, though in this case the little guy is anyone making less than $400,000 a year. So we still don’t know where the money will come from.

JON:

The gas tax is really regressive so maybe it’s good to not use it anymore.

CASEY DINGES:

You know, charges in the future [with electric cars] will be for vehicle miles traveled—how many miles do you actually drive a year? 10,000? Or do you just drive 5,000 miles? But the penetration of electric cars is still less than two percent.

JON:

In the meantime, at least we know where the money is—with billionaires who pay no taxes.

CASEY DINGES:

At ASCE we calculated that we need to spend $260 billion a year—$2.6 trillion over ten years—to get the Report Card grades up to a B average. That money can come from any of three levels of government and the private sector. It sounds like a lot but we’re talking about one percentage point of GDP to be invested.

At the ASCE we calculated that we need to spend $260 billion a year—$2.6 trillion over ten years—to get the Report Card grades up to a B average.

JON:

That would be very small for a business as a percentage invested in plants and equipment and maintenance.

CASEY DINGES:

And when you think about the costs to every American: The average motorist will pay over $1,000 a year because of damage to their car due to road conditions. We lose six billion gallons of treated drinking water to our leaky pipes and there’s a water main break every two minutes in the United States. I like it when Biden says, “Inaction is not an option.”

JON:

There seems to be bipartisan agreement on that but people want to see faster results. It took only 13 months to rebuild the Minneapolis bridge. Only 16 months to build the Pentagon during World War II. I live outside New York, where the Gateway Tunnel under the Hudson is essential work—the tunnel is 110 years old, damaged by Hurricane Sandy, and, pre-Covid, carried 150,000 people daily into the city. But they say it will take seven years to build. That’s ridiculous.

CASEY DINGES:

The Minneapolis bridge and the Pentagon shows what we can do if we’re really focused, right? Of course, you have to do studies—it’s always really complicated, with a lot of interests and factors to consider. Yes, we can address critical issues in a more timely fashion and make go-or-no-go decisions on projects more expeditiously. But people want safe infrastructure. They don’t want to have to worry about going to sleep at night in a building or going across a bridge or through a tunnel.

But people want safe infrastructure. They don’t want to have to worry about going to sleep at night in a building or going across a bridge or through a tunnel.

JON:

Speaking of the safety of buildings, which is obviously in the news—it’s only since 9/11 that the federal government has had any role in that at all.

CASEY DINGES:

At that time, the mayor of New York was in charge, and that was Rudy Giuliani. So ASCE set up a building assessment performance team and got some money from FEMA to do an analysis and try to understand why the towers fell. It became clear that the federal government needed to go in and investigate the way the NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] does after fatalities. So a bipartisan bill was passed in 2002, the National Construction Team Safety Act, which gave this responsibility to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the Department of Commerce. NIST has many research assets including the Fire Research Lab.

JON:

The Commerce secretary, Gina Raimondo, is a badass, so they’ll get to the bottom of what happened to the building in Florida.

CASEY DINGES:

I’m told that [NIST] people are already there. If there’s other [vulnerable] buildings, people are going to want to get the word out on that—or is this a one-off?

JON:

What does your gut tell you about this?

CASEY DINGES:

My gut tells me to be patient and to realize that there are multiple issues. Just when you thought you might have figured it out, there might be another wrinkle. They’re looking at all aspects of this—the foundation, the water issues, proximity to the ocean, 40 years of salt air exposure to rebar. It could be columns giving way, or a slab became disconnected from a vertical support and that could be enough to cause the floors to pancake down. It’s hard to speculate. They’re listening to eyewitnesses saying there were three booms. What was the first one if the other two booms are the two towers that came down? There’s a lot to look at but I’m pretty confident they’ll come up with an understanding of what happened here.

JON:

Look, its Florida, Jake. My bet is that there will be something like sketchy inspections, or inferior building materials, or corruption at a management level— some kind of scandal.

CASEY DINGES:

They can do forensic analysis where if the concrete wasn’t right, they’re gonna find that out. This building stood for 40 years—were they cutting corners on maintenance?

JON:

As you know, Casey, I like to ask my Old Goats a few personal questions. So here goes: How did being an orphan affect your life? Did it make you stronger? Fuck you up?

CASEY DINGES:

There’s a lot to unpack. Certainly when a kid loses parents at a young age there’s a long grieving process. I’d say, a good lifetime of grieving, though not to the point of disability and not being able to have a career and family. But it is a loss and a pain that has stuck with me for a long time. Maybe it gives me a level of patience, Jon, to stick to an issue for two decades before it comes to fruition.

You know, those seven years after my mom and dad died and before moving off to college felt like my own little Vietnam War. There was no one else other than my brother who was going to truly understand what this felt like, in terms of the loss and the challenges of dealing with a new family. So there’s just a kind of stick-to-it-iveness determination—kind of willing yourself to get through a day or a month. But I had enough good things going on in my life—things I enjoyed doing, fun times as a kid growing up on the North Side of Chicago—including sometimes with you and your family. So there were just enough things to be hopeful and positive about the future.

In terms of my career, I drew on family threads. My mother’s dad was a political opponent of Hitler—a maritime lawyer, part Jewish, who worked closely with political leaders in the free port city of Danzig [now Gdansk, Poland], right on the German-Polish border. He got here in 1938 and ended up on the faculty of Michigan State University and became an advocate for the U.S.. entering the European conflict. I don’t remember meeting my grandfather but that little bit of family reinforcement convinced me that Washington would be an interesting place to have a career.

And they have really good softball leagues here.

JON:

I know you’re now a Nats fan as well as a Cubs fan. I’m really mad that the Nats got Kyle Schwarber from the Cubs. But we still have the great David Ross as our manager.

After Game Seven of the 2016 World Series, I scammed my way into the Cubs dugout in Cleveland, where Ross had just become the oldest player ever to hit a homer in the World Series. I’m babbling about how I grew up six blocks from Wrigley Field and me and my friends Casey and Billy used to pack a brown bag lunch and sit in the Bleachers when the Cubs were so bad, and have a 25 cent Frosty Malt. He’s sitting on the bench and he stands up and wraps me in his arms and I can smell his sweat, and he says, “You deserve a hug, too.”

CASEY DINGES:

OK, Jon, I will vicariously feel that hug.

In the meantime, the Nats are giving me this 2019 vibe all over again. [when the Nationals won the World Series]. I’m not feeling the 2016 vibe.

JON:

I hope you’re wrong. Thanks Casey.