Ruminating with Calvin Trillin

The legendary writer on rhyming Ron DeSantis, why his parents named him Calvin, and his mother making chopped liver with Miracle Whip.

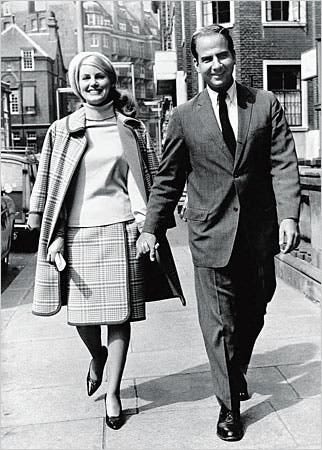

Calvin “Bud” Trillin, now 87, has for decades been in the first rank of American non-fiction writers. He’s a journalist, novelist, humorist and — just in the last few years — a playwright. Raised in a Jewish family in Kansas City, Bud served in the army, graduated from Yale, where he was chairman of the “Yale Daily News,” and covered the civil rights movement for “TIME” before becoming a staff writer for “The New Yorker” and a columnist for “The Nation.” While he and his wife Alice (who died in 2001) lived in Greenwich Village — where they raised their daughters, Abigail and Sarah — his beat was always America. If you include the collections of his wry and deeply-reported magazine pieces, he has written more than 30 books. Among my favorites are “Floater” (a novel about a writer for a newsmagazine), “Alice, Let’s Eat” (one of several fun books about what he calls “vernacular food”) and “Remembering Denny” (an account of the life and death of a friend). His book “About Alice” is an exquisite act of love. I’m not sure I’ve ever met anyone with an unkind word about Bud, who is invariably gracious and droll.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Are you feeling a little better about the world since the midterms?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I am, though just in the last week, Marjorie Taylor Greene said she and Steve Bannon would have done a better job organizing January 6th, they would have had guns and they would have won. That was the same week as the reporting on the attempted coup in Germany.

I remember after George W. Bush was reelected, I was the emcee of some Nation event and I said, “If I seem less despondent to everybody else in this room, it’s because I already have a house in Canada.” [A home in Nova Scotia]. Of course I would never leave.

JON:

If Heinrich the 13th had shown up, pre-Trump, it still would have been scary but also some pretty good grist for humor.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

People in the small joke trade, which is one of the trades I'm in, look upon things that are not necessarily good for the country the way dentists view tooth decay: It's a pity, but where would business be without it.

JON:

What’s your take on DeSantis?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

As a deadline poet, my problem with him is that his name doesn’t rhyme with anything, except praying mantis. And he might not make it. Remember when George Allen was running for senator in Virginia?

JON:

Yeah, and then he said “macaca”.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

He was the perfect candidate, they really loved him and then he’s gone.

JON:

The same thing happened to Governors Scott Walker of Wisconsin and Tim Pawlenty of Minnesota.

CALVIN TRILLIN::

And Rudy Giuliani. He was called “America's mayor”. I even said something rather nice about him. I said that his behavior after 9/11 showed that there were some times when a paranoid control freak was just what the occasion calls for.

JON:

And I wrote something about him in Newsweek that was so bad — so saccharine — that it was republished in Readers Digest.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

Then he tried to stay in office after the election of his successor, just like Trump.

JON:

Remember how in 2008 Giuliani was leading in the polls nationally and so he decided to skip New Hampshire and concentrate on Florida, where a bunch of New Yorkers had moved and where he was way ahead? It didn’t work.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

Don’t you think the Republican candidates will split the anti-Trump vote [in the primaries]?

JON:

I don’t. I recently heard a rumor that they’ve had secret contacts and informally agreed that they’ll drop out after the first few primaries and unite behind one guy to square off against Trump. I don’t think that’s gonna be Mike Pompeo or Chris Christie or Mike Pence. So that likely leaves DeSantis, who will have a good shot against Trump even if he’s a cold fish in person. And as bad as he is — this new anti-vax thing is so cynical and dangerous — the idea that he’d be smarter and thus worse than Trump is wrong. DeSantis is Nixon. Trump is a unique evil.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I agree with that.

JON:

Your name is Calvin Marshall Trillin, but your father was a Jew from Ukraine. What was that about?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I always say that Marshall is an old family name. Not our family, but an old family name.

I think that he wanted something that he thought, incorrectly, would sound good at Yale. I'm virtually certain that he had no idea of the connection between John Calvin and the Presbyterian Church. I think he just thought it'd be unusual and sort of distinguished.

JON:

We Midwestern Jews are different that way.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I got a call once from a Chicago rabbi who wanted me to speak.

And he said, “We're doing a series on the American experience as seen by Gentile writers.” So I said, “Rabbi, I don’t qualify as a Gentile writer,” and he said, “Oh, I thought the name…” I was trying to get out of the speech – I knew from childhood that rabbis always get a deep discount – but he persuaded me to come. Then he said, “I like titles that are long and have a colon in the middle.” And I said, “Well, there's one title that I’ve talked about using but I’ve never actually given the speech: Farm Price Supports: A 30-Year Overview Concentrating on but Not Exclusive to Soybean Pricing Structures.”

The rabbi said “Perfect.” Half an hour later, he called and told me the nice lady who types up the temple bulletin said about that title, “What's the Jewish content in that?” And he asked me if I had another title. When I said I did, he said, “Does it have a colon in the middle?”

I said, I said it did: Midwestern Jews: Making Chopped Liver with Miracle Whip. After my talk, a woman came up and said that was a very interesting metaphor in your title, and I said, “Alas, madam, that was no metaphor. That was my mother’s recipe.”

JON:

Your father wanted to be a writer. I loved it when he was collecting curses and one from Miami Beach was, “May your injury not be covered by workman's compensation.” When I read that line, I thought immediately that it sounded exactly like the kind of thing that you would have written 50 years later. Is there a gene for writing?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

Maybe there's a gene for people who aren't very good at mathematics and business and therefore take themselves for writers. I always say that I couldn't persuade my math teachers that many of my answers were meant ironically.

My father was a grocer for most of his working life but he had a restaurant for a while. And he put rhyming couplets on the menu every lunchtime. He wrote mainly about pie.

Let's go, warden, I'm ready to fry. My last request was Mrs. Trillin's pie.

I always said that my father's aspirations for me were that I become President of the United States and his fallback position was that I did not become a ward of the county. And I think that's true when you look at your own kids.

Sometimes you think, “How did we produce such a special person?” And sometimes you think, “Will this kid be able to find his way out of the rain?” I like to think that he considered journalism sort of an acceptable middle course between the presidency and being a ward of the county.

When the Kansas City Schools ran out of money one year and ended early, my sister and I were sent to secretarial school to learn how to type.

My father had read this turn-of-the-century book called Stover at Yale.

He didn't go to college and he thought Yale was a place where the industrialists sent their sons, and so I would sort of step onto this escalator and rise in the world.

“Maybe there's a gene for people who aren't very good at mathematics and business and therefore take themselves for writers. I always say I couldn't persuade my math teachers that many of my answers were meant ironically.”

JON:

How did you end up at The New Yorker?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I’ve always suspected that [William] Shawn wanted somebody to write about the South and he hired me from TIME without having read anything I’d written other than a cover story that was a collaborative effort.

My father asked, How much would you make at The New Yorker compared to what you're making at TIME? I believe I was making something like $12,000 at TIME. And I said, “We hadn't talked about that.” That was one of the times when my father thought: is he smart enough to come in out of the rain?

I was in the Southern bureau of TIME from the fall of 1960 to the fall of 1961, a busy year in the civil rights struggle. And I’d thought I might get a leave fromTIME and go back to the South and write about individuals, because a lot of the coverage had been about what the NAACP is going to do, or what the power structure the city's going to do.

JON:

When you look over all this period, is there one moment that sticks out for you? I know you wrote a book about when Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes integrated the University of Georgia in 1961, but did you actually witness them walking in with Vernon Jordan, a young lawyer at the time?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I used to joke with Jordan about this. When we walked around the campus, I tried to see where the angle was for people throwing rocks, and I stayed behind Vernon because he was so big.

I was on the first bus of the Freedom Rides. But the one thing that sticks out wasn't a violent or romantic thing: I was talking to Charlayne on the phone. She was in a room by herself, and sometimes harassed by the lovely southern belles in her dorm. So she was lonely. She had given a speech in Savannah, and I said, “I hear the train is great between Savannah and Atlanta.” And she said, “not where we have to sit.” I’d read the usual books about segregation, and I knew all about Plessy vs Ferguson and all that. But my instant response in my head was not any of that. It was, “They can't make her sit back there.”

I think it was the first time that I really understood how personal it all was.

JON:

I think people are interested in how you've made a living, considering, as you famously said, The Nation pays in the high two figures.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

That was their offer.I told my agent to play hardball, and he got them up to a hundred. Eventually, I left The Nation for newspaper syndication. And then I was inspired by John Sununu to write what we called deadline poetry. The first one was called, “If You Knew What Sununu.” I took that to the wily and parsimonious Victor Navasky [the editor of The Nation] and he said maybe I could do one of those every issue. At that point, the highest payment for poetry was at The New Yorker, which paid $10 a line. So a two-line poem came out to $50 a line. I realized I could be the highest paid poet in the country because I will get $100 no matter what.

When George W. Bush's college transcript was revealed to no effect on the campaign, I wrote:

“Obliviously on he sails, with marks not quite as good as Quayle’s.”

I wrote a poem in 2008 about Mitt Romney that I now feel a little bad about because he’s one of the few people standing up for the Constitution.

Mitt Romney as Doll

Yes, Mitt’s so slick of speech and slick of garb, he

Reminds us all of Ken, of Ken and Barbie–

So quick to shed his moderate regalia,

He may, like Ken, be lacking genitalia.

JON:

The writer Sarah Lyall described Alice as your “muse, cheerleader, literary interpreter, straight person and buster of bubbles.”

CALVIN TRILLIN:

That's all true.

JON:

I like this poem:

A Conversation with Someone Who Can’t Believe That Alice Is Fifty

“No way,” you say.

“It simply cannot be.

I would have guessed

That barmen often ask her for I.D.”

“I know, I know.

She has that youthful glow

That still gives young men vapors.

She’s fifty, though.

I’ve seen her papers.”

How did Alice help your work?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

For 15 years, I did a 3,000-word piece for The New Yorker somewhere around the country every three weeks. When I got home, I would write what was called in our house “the vomit out”— I’d vomit it out without even looking at my notes. The language would deteriorate as I went because I didn't pay any attention to that. I was always concerned that the “vomit out” would be found at The New Yorker by the cleaning women, and they'd read it out loud, and say, “He fancies himself a writer!” And then they laugh uproariously and smack their brooms against the desks like hockey players.

I’d show the next draft to Alice. If I heard laughter from the next room — that is, if the piece was supposed to be funny — that was very good. If I heard a sigh, not so good. She [Alice] wasn’t afraid to tell me what didn't work, what she didn't get, or ask why I didn't do this or that.

Alice was an experienced editor and people would give her their work to look over. One of them was Larry Kramer who gave her a draft of 1600 pages. She suggested some cuts.

JON:

Larry Kramer [author and gay rights activist] lived in the same building in the Village as [Mayor] Ed Koch.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

At 2 Fifth Avenue. Apparently, Kramer had yelled at Koch when Koch was being shown around the building, and, once Koch moved in, Kramer had been told by the management that if he said anything to Koch, he was going to get evicted. One day, Kramer and his dog, Molly, were at the mailboxes at the same time as Koch. There was silence for a long time as they opened their mailboxes. And then Kramer said, quite loudly. “Molly, that's the man who murdered all of daddy's friends.”

JON:

You’ve specialized in writing about regional food.

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I’ve never written restaurant reviews or written about what was called “fine dining.” I used to call the fine dining restaurants in American cities, “La Maison de la Casa House.”

JON:

Having been burned by the ridiculous reaction to the totally innocuous poem about Chinese food [that mentioned the marketing of dishes by province], are you in the camp that says it's not worth the tsuris to respond to the hyper-woke stuff?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

I was gobsmacked. I had no idea that people would take it that way. [The flap] lasted a week or two. Fortunately, I wasn’t then and am still not on social media. But I later wrote a piece about a Trumpian candidate who got into the primaries and accused Donald Trump of wearing a corset. And someone at The New Yorker said, “Aren't you afraid you'll be accused of body shaming?”

On the other hand, we can get words in The New Yorker that we could never have before. In an article about a guy who was accused of being a drug dealer and was driven out of the community, one woman I quoted said, “He had asshole issues that didn't have anything to do with drugs.” Wonderful line and I would have hated to give that up.

My father and [William] Shawn were born within a few months of each other, and the harshest thing I ever heard my father say, when he got really mad, was, “For crying out loud.” Shawn simply didn’t want off-coller language in his magazine, and my father would have felt the same way. That was OK with me, except when it came to quotes important to the story. I turned out to be the accidental pioneer in using“fucking” in The New Yorker. The story was about a farmer in Nebraska whose farm equipment was going to be repossessed. And at some point, he said, it's “the goddamn fucking Jews.” That guy probably never saw a Jew in his life. It turned out he had fallen into the hands of prairie fascists.

I went in to see Shawn and told him it was from a state police transcript. We discussed using “f dash dash,” but he said no, that’s silly and we will never do that. And then he said, go ahead and use it. And I was so surprised that I sort of backed out of the office. I was afraid any sudden move would make him change his mind. It went into the magazine, and, as far as I know, nobody said a word about it.

JON

At The New Yorker you worked under William Shawn for many years. What was the special quality he had?

CALVIN TRILLIN:

Well, I think that Shawn had a talent for listening. I always thought that hordes of writers who walked out of his office after talking with Shawn about possible stories must have thought, “At least one person understands what I’m trying to do.”

JON:

I was covering media for Newsweek when The New Yorker was sold to Si Newhouse in 1985, I called Roy Cohn, who told me that he and Si and Gene Pope, the founder of the National Enquirer, were best friends at the Horace Mann School and they talked every morning on the phone at 6:30 a.m. When my story came out, that was the lede — new owner of The New Yorker is Roy Cohn’s best friend — and you could almost see the top of the old New Yorker building blow off. People were really upset. But it turns out Newhouse was a good owner and you and a lot of other great writers have continued to thrive there.

Sometimes things turn out better than we think.

Thanks, Bud.

Jackson, 1964 is a collection of some of Calvin Trillin's astonishing essays on race in America. It's on my bookshelf and I recommend that you get it for yours, if you don't already have it.

Another great interview!