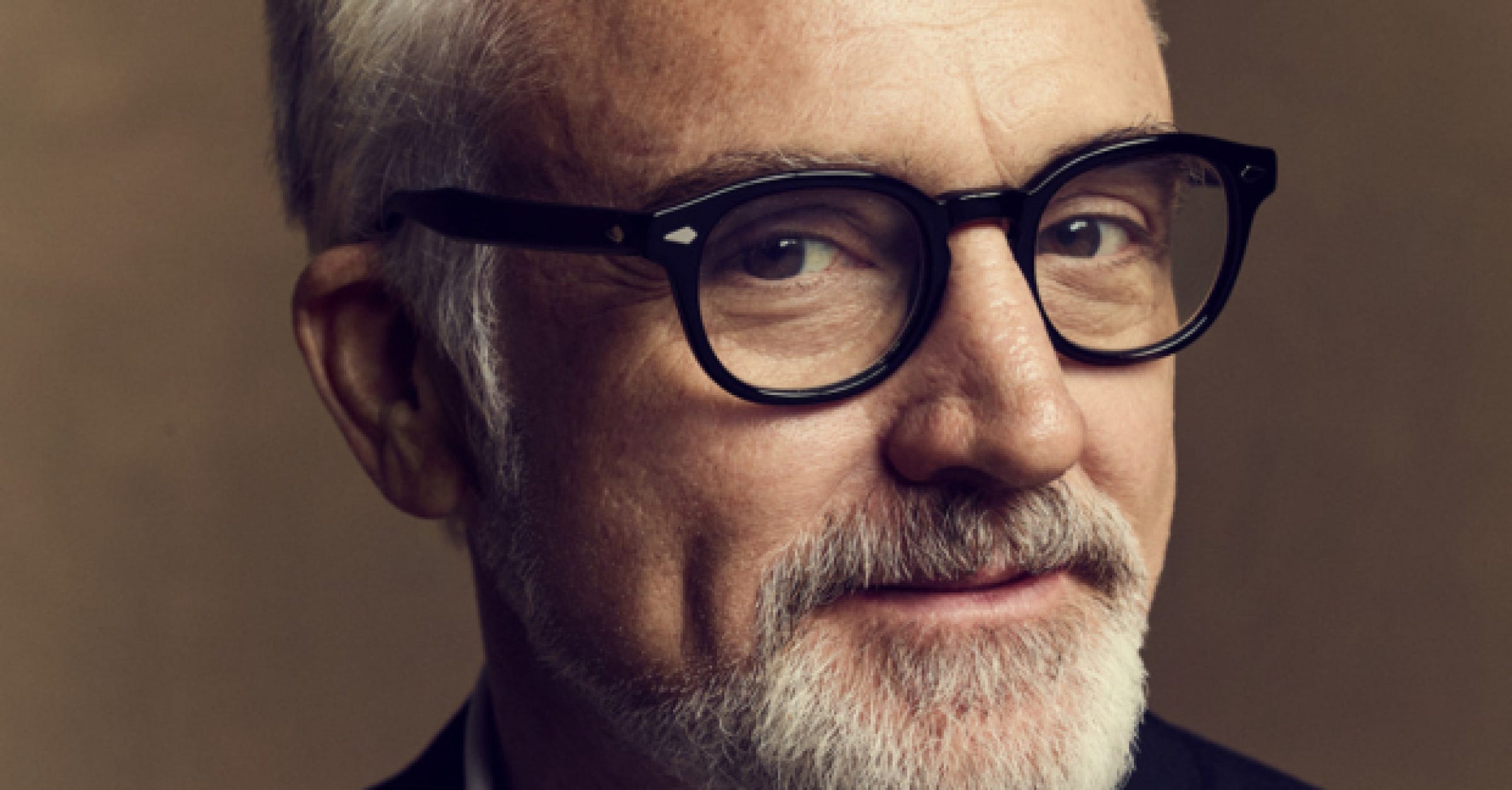

Ruminating with BRADLEY WHITFORD

About show business (more than The West Wing) and politics (more than Trump)

I first met Bradley Whitford in the late 1970s when he was my sister’s college boyfriend. After he graduated from Wesleyan and Juilliard, we stayed in intermittent touch and I saw him in several plays in New York, including A Few Good Men, which is where he met Aaron Sorkin. My family had a thrill visiting him on the set of The West Wing, where his Emmy-winning role as Josh Lyman made him famous. Bradley met his second wife, Amy Landecker, on the set of Transparent. His role on that show playing a crossdressing businessman won him another Emmy. Over the years, I’ve found him to be not only a terrific actor but a thoughtful political analyst. At 62, his career is still going strong. These days he’s in Toronto shooting Season Five of The Handmaid’s Tale, where he plays the villainous Joseph Lawrence.

JONATHAN ALTER:

Hi, Bradley.

How long is this shoot?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Well, this is a weird situation because I'm up here trailing people. I'm going to direct an episode later in the year in a block with Lizzie Moss and she's directing the first two episodes. So I'm here basically until July, which is just insane.

JON:

I was thinking about when we met when you were at Wesleyan and was reminded that you were on the board there and that I love the line of Wesleyan President Michael Roth: “Nowhere in the Constitution is there a right not to be offended.”

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

It's very tricky in acting schools now. I was [a guest lecturer] and some people were talking about how Shakespeare shouldn’t be writing female points of view. And then it got into a conversation about triggering and I ended up standing on a chair and saying: “How the fuck do you teach the Holocaust?”

JON:

Todd Gitlin, the great liberal critic and activist who died recently, once wrote that “While the right has been busy taking the White House, the left has been marching on the English department.” But the idiocy marches on. Eric Zorn, a former Chicago Tribune columnist, reported this in his Substack newsletter:

University of Illinois at Chicago Law School professor Jason Kilborn administered the final exam in his Civil Procedure II class.

One of the written questions posed a hypothetical scenario in which a woman claimed that she “quit her job … after she attended a meeting in which other managers expressed their anger at (a different employee), calling her a ‘n____’ and ‘b____’ (profane expressions for African Americans and women) and vowed to get rid of her.”

The blank spaces appeared on the exam but the UIC Black Law Students Association was still deeply offended and demanded and received an apology from the professor. These are law students about to practice in a gritty, crime-ridden city and they can’t handle blank spaces!!!

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Years ago I did a guest shot on Shameless, which is an intentionally envelope-pushing show with some very rough stuff in it. And a crew member was laughing about the fact that so many words and situations that were depicted in the script were in total violation of the sexual harassment seminar they had just had. I actually think those seminars have done a tremendous amount of good. In my experience sets are much safer, much more respectful and much more inclusive than they were twenty years ago.

This perfectly reflects the hypocrisy in Hollywood of, “Look, we're gonna protect ourselves legally but we’re also going to make money off this till the cows come home.” On the one hand, there is zero tolerance. On the other hand, envelope- pushing.

“This perfectly reflects the hypocrisy in Hollywood of, ‘Look, we're gonna protect ourselves legally but we’re also going to make money off this till the cows come home.’ On the one hand, there is zero tolerance. On the other hand, envelope-pushing.”

I learned very quickly coming up in regional theater back in the ‘80s: Do not go to the after-play discussion. Someone will always say, “I didn't think you were very good. I didn't like this production. That didn't make any sense to me.” No good comes of it.

And I learned very quickly, don't read reviews of plays.

JON:

So you don't read reviews? How do you resist?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Well, you can't read them when you're doing a play. There's an element of camaraderie, and rah-rah and faith that allows you to go out and make a spectacle of yourself. My faith in myself is not sufficient to sustain a public hit in the midst of a run of a play. But of course reviews truly don't matter in television, and they haven't for a long, long time. The New York Times review of West Wing when it first came out was horrible.

I don't even think The Sopranos is immune. It was justifiably adored by critics, but once you get into year three and year four, the reviews are just sort of bitch sessions that are basically saying the show should have ended a couple of years ago.

JON:

Saying they “jumped the shark.” Henry Winkler told me a couple of good stories about how that whole thing got started.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

With Trump, unfortunately, there’s no jumping the shark. The most disturbing thing to me about what's going on now is that we kept thinking of Trumpism as sort of an aberration. But I’ve never seen it ebb. I thought when Access Hollywood happened, he's gone. When the first Charlottesville happened, I thought, you know, that’s it. And then impeachment. Nope. Losing the election. Nope. It’ll be January 6th. Nope. I haven't seen it yet.

JON:

His people will be making pilgrimages to his grave and touring Mar-a-Lago for 150 years. That’s a really bitter pill to swallow. There’s no grave for Hitler because the Allies didn't want any place for [his followers] to go. We won’t be so lucky.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I was always obsessed with Neil Postman's book, Amusing Ourselves to Death. And from my weird point of view at the sort of intersection of entertainment and politics, I realized a long time ago that you can ejaculate on an intern in the people's White House and you will be forgiven. You can go to war based on false intelligence without a plan and make the most disastrous foreign policy move in the last 1000 years, and you will be forgiven. The death penalty in politics is reserved for being bad on TV. Howard Dean screams and it’s “Get the fuck off! Get out!” Al Gore sounds kind of pedantic and it’s,“Fuck you! Get the fuck off my TV!”

JON:

That’s what happened to Jimmy Carter, too.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

It's terrifying to me because I make my living doing this and take it from me, it's a pretty shallow value. Trump's superpower is having no shame—that’s great television. It's like the old show business advice, “Don't work with dogs or babies—you can’t take your eyes off them.” Same thing could be said about a person who has no capacity for shame. It's like encountering somebody on the street who's not at the mercy of gravity. It's fucking riveting. And it’s really, really dangerous.

Trump's superpower is having no shame—that’s great television. It's like the old show business advice, “Don't work with dogs or babies—you can’t take your eyes off them.”

JON:

I gave a speech in Virginia recently and in the car on the way to the airport the driver was a Trump voter but not a Trump fan. One of the things that he said was that he didn't like it when people in show business started talking about politics. So what what do you say to a guy like that?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I would remind him that if he voted for Trump, he voted for somebody who was in show business. And Sean Hannity is a show business celebrity. Bill O’Reilly is, too.

JON:

And a lot of these people were perfectly happy to have Arnold Schwarzenegger in politics.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

When West Wing happened, all of a sudden there's press and it's a political show, and people are asking you things. I felt our government was making a horrible mistake starting wars and it was a time when you feel like your kids’ future is being attacked every time the newspaper hit the ground. Ultimately, I decided I didn't want to shut up about it. After all, there’s nothing less democratic than telling other people to shut up. So the people who tell other people to shut up, should, you know, shut up.

I've learned going back to Wisconsin [where he was born] every cycle that it does absolutely no good for a predictable Hollywood lefty to tell people how they should think. That's not helpful. But you can be effective in smaller races in getting people registered to vote or stealing a local news cycle for the guy who's running for something like attorney general. The weird value that I can bring to a campaign is attracting cameras.

JON:

I know you know about Run for Something.

Do you think that the creative community is going to put money behind these local races?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I really hope so. The difference is that Democrats want to change culture and Republicans want to change politics, and the later is more powerful politically. Unlike Democrats, Republicans like the Koch brothers have a direct financial interest in the outcome, which they can change with a ridiculously small percentage of the money they have.

I think that politics is the way you create your moral vision. Culture is vitally important. But you have to follow though with the hard work of politics. At the end of the day, Will and Grace won’t help you if you have a pre-existing condition.

It’s hard to remember that Republicans didn't want Trump at first and now it's become a perverted, racist, fascist cult of personality. The stepping stone from the old Republican Party to where we are now was Republicans realizing Trump was going to be a delivery system for their business and judicial agenda. And Democrats go, “Okay, that's not the way we function. We need to fall in love. We need Barack Obama to come along so we can endow him with our infinite hopes.”

JON:

Democrats fall in love, Republicans fall in line. Even with fascism.

How about using the creative community to drive change through their art?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I thought Don’t Look Up was great and I’ll tell you an interesting story about Get Out. When I read the script, it ended when the character Chris kills everybody in the driveway. You see the police car come in, and then it faded into him being visited by his [Black] TSA friend in prison. And he says, “I know the truth. I'm going to get you out of here.” And Chris basically says, “It's okay, we stopped them.” I thought it was a really good ending to the movie. And then when I saw it, Jordan [Peele] had changed it in such a brilliant way. He reshot the ending so that when you see a police car pull up, you see a black guy in a driveway with a bunch of dead white people. And then the rewrite was, you see the door open and it says “TSA” and you realize that it's not the cops and Chris is not going to jail. There's something so interesting about that moment, which I talked to Jordan a little bit about. That movie penetrates and it’s because of the release in that laughter. When you see TSA, you can be the most racist person in the world but when you laugh at that, you are acknowledging the fact that Black people are in danger around police. And it's such a more powerful way to end it. I just thought that was such a brilliant piece of storytelling. If he had stayed with more of a political statement about mass incarceration, it might not have penetrated that way.

JON:

When I was in high school I briefly thought that I might want to be an actor and my father who never otherwise gave me any career advice said, “Don't do that. It's just too hard on your personal life. It's a gypsy life. You don't have any control.” Did your parents ever try to talk you out of it?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

My parents had three kids and then a big break. I joke that my brother was sort of a mistake, and I’m like, the mistake’s friend. So they had arrived at a pretty healthy parenting philosophy, which was, “Keep them out of traffic and they’re going to be what they're going to be.” They weren't overly invested in it. My father was a frustrated musician. He was an amazing piano player and had perfect pitch. But coming out of the Depression, that was not an option. So he became a businessman, and stayed at one [insurance] company for a very long time.

I always got a sense that he kind of got off on on the fact that I wanted to be an actor. After I went to college, I went to Juilliard for four years but I remember never wanting to say that I wanted to be an actor. I still feel a little embarrassed saying that—it seems vain. But it was always what I loved to do. I was in as many plays as I could from seventh grade all the way through college. I love the beautiful, intimate atmosphere of [the theater]. But my entire class at Julliard got together about five years ago, after 34 years. After four years at Juilliard, three of us [out of a class of 25] make a living acting.

JON:

Wow. That’s brutal.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

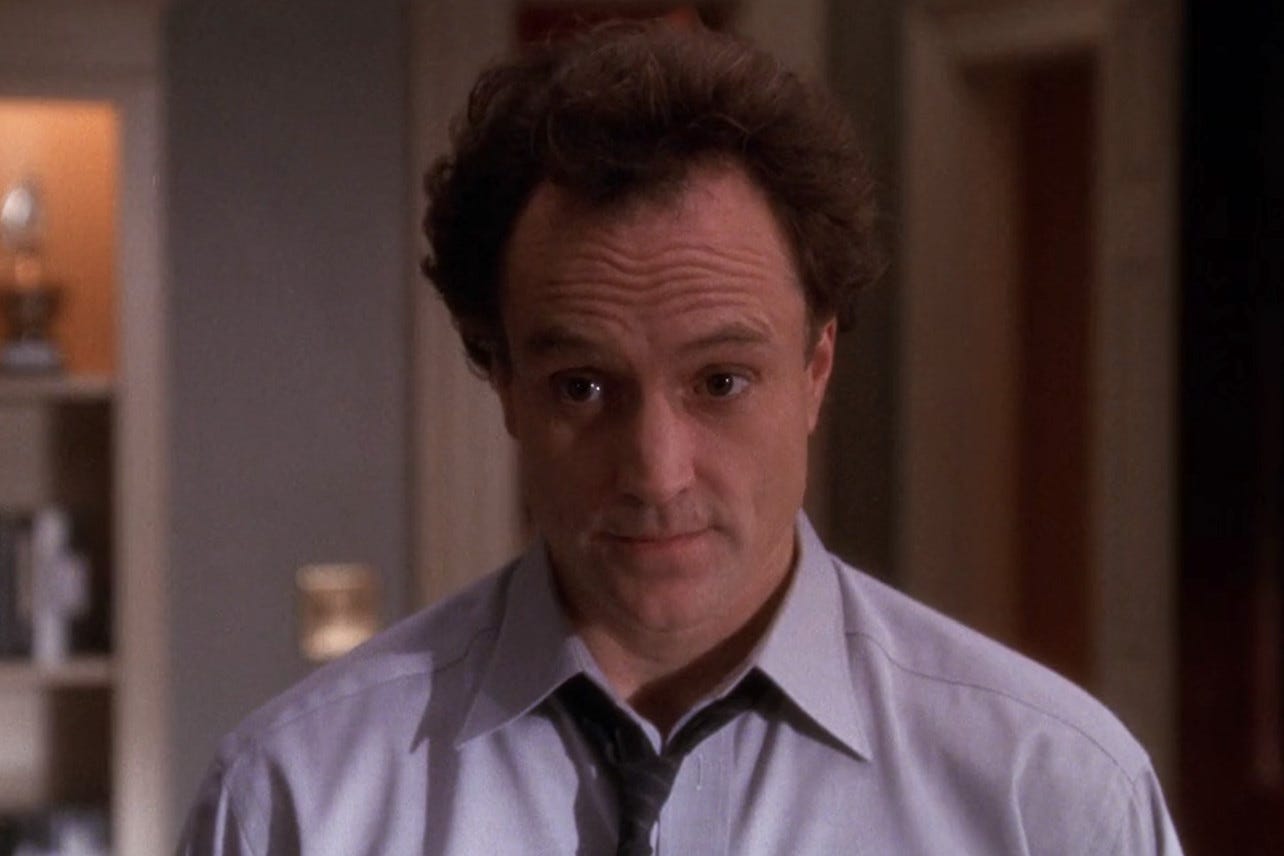

It's really brutal and yes, you have to be talented, but your talent gets really enhanced with luck and opportunity. When people asked me how I got West Wing, I realized that it was because I got cast being an asshole in Revenge of the Nerds II. I met Tim Busfield on that and we were both theater geeks and ended up being in A Few Good Men together. [An Aaron Sorkin show].

JON:

But that was a departure from your film and stage career.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I remember driving over the hill to Warner Brothers and thinking, “I'm going in to shoot a scene with Martin [Sheen] and Allison [Janney] and John Spencer, and Aaron's writing is just phenomenal. But I remember also thinking, “Man, don't tell the feature people about this.” But then I didn’t have to worry about reviews anymore. I have this long relationship with this character and with the audience. And you just you don't get that in film. It’s interesting— in this world of fractured attention spans, there is this incredible desire to immerse yourself in these sprawling Dickensian stories.

When you're watching The Sopranos and Tony comes in and barks at Carmela in Season Five, there's no way you can have that connection in a movie because you've been in bed with them for five years. You know the betrayals, the weight loss, the weight gain.

I always joke that we're descending into fascism and the planet’s on fire, but we're in a renaissance of shoe comfort, cosmetic dentistry and storytelling. It is an incredible time to be telling stories because you no longer have that obligation to be broadcasting [to a mass audience].

Get Out is a perfect movie but that's a movie story. There are certain stories that need to be told in that form. Others work better at length. To me it's almost like the relationship between a short story and a novel. And more people read novels than short stories.

JON:

It’s amazing that just 20 years ago you would be actively hurting your film career to be in a television series.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Yeah, when I was coming up in the theater, you did not do that. I remember Kathy Bates was offered some sort of television thing and she’s like, “No, I don't want to fuck up my theater career.” Now it’s the absolute opposite. You know, on Handmaid’s Tale we’re going into our fifth year, and it's this fascinating sort of deep relationship with the character, with the show and, most importantly, with the audience. It’s very intimate, because you are in bed with them as they watch.

JON:

Why do you think that over the years you've played so many bad guys?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

People bitch about typecasting but it's sort of a shitty compliment. In the movie business, they want to make sure you can do it [the assigned role]. They're not there to explore the nether regions of your possible talents. So if you do it successfully once, they want that again. It was good for me. Our generation’s version of a Nazi was a privileged white guy with a job.

It’s sometimes even more fun than the lead. You can chew some scenery. I remember the very first time I ever got recognized. In the 80s I was giving some change to this homeless guy in New York, and he looked up at me and goes, “Oh, my God. You're in those movies.” And I was like, “What performance was that?” I was thinking, “Oh, wow.” And he says, “You always play that fuckin’ asshole.” I remember going to my agent because I was worried about playing an asshole again, in Billy Madison. I thought it could hurt my career. He said, “I think you should take it. You don't have a career to hurt.”

JON:

You’re 62 and work all the time. What do you think extended your career when so many other actors your age are doing other things or maybe living off their residuals.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I've always been lucky. When my kids were going into college, I was doing a lot of micro budget movies that didn't work. The transition to the kind of television streaming that we have now hadn't quite happened in the business. And I remember thinking, I don't know if this is gonna work. And the thing that honestly turned it around was Get Out, which nobody had any idea was going to happen. I had nothing to do with making it work.

JON:

Well, that's not true.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I love actors. I feel like they're my tribe. And I understand how elusive a really great performance can be. But at the end of the day—and this isn't helping me negotiate— a lot of people could have played that role in Get Out and been great. And the movie still would have been great. Acting talent is actually relatively common. There's no moment in storytelling where a great writer like Arthur Miller comes along and they say, “We just don't have the actors to do it.”

“Acting talent is actually relatively common. There's no moment in storytelling where a great writer like Arthur Miller comes along and they say, ‘We just don't have the actors to do it.’”

JON:

Aren’t all actors insecure?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

They should be. It's really not helpful for actors to aspire to confidence. One of the great things about James Gandolfini was his bringing his complexity, his fear with him. He was not a confident actor and he was great. You know who has a lot of confidence? Donald Trump.

JON:

How did you end up on Transparent?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I always joked that I was the only actor who had never done Law & Order. Then I did a Law & Order SVU episode where I played a child molester. Jeffrey Tambor was in it and I wanted to work with him again. And that’s how I ended up in Transparent. There was a fascinating role of a homophobic crossdresser in the 90s and Joey Soloway [the show runner] reached out to me because Jeffery suggested me.

JON:

That wasn’t your first time on an Amazon show. In 2014, I asked you to play a cameo as a senator in one scene with Janel Maloney, who also plays a Republican senator, in an episode of Alpha House (Season Two, Episode 6), which was in Amazon’s very first slate of shows. You were nice enough to fly all the way across the country for that. A couple of years later, Transparent had a big social impact.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Nobody knew that show was going to have the impact that it had. I’ve been really lucky to be a part of shows that have a high creative aspiration and also become part of the cultural discussion. That's pure luck.

JON:

How much can culture change things?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

I always think back to the time I did a Clint Eastwood movie. And I'm sitting next to Clint Eastwood in his director's chair, and his heart is beating like once every three minutes. And it was right after he had won the Oscar for Unforgiven. And I have a Sunday New York Times and I open up the Arts and Leisure section and there's a picture of him with the headline, “Clint Eastwood's Vision of America.” And I said to him, “Did you see this?” And he goes, “Vision of America? Ten years ago, I was working with an orangutan and now they think I'm Gandhi.”

He never yelled “Action!” because when he did Westerns it was always hard to get horses on their mark. The directors would yell “Action!” and the horses would rear up. He said, “Well, I think actors rear up, too.” So he would [silently gesture to start the filming]. He famously does not do a lot of takes, but at least he was really kind. He talked about how he felt disrespected as an actor coming up, so he was always nice to us.

JON:

What movie was that?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

A Perfect World. [1993] I got to kill Kevin Costner.

JON:

I remember when you were with Harrison Ford in Presumed Innocent. And you were cross-examined by Denzel Washington in Philadelphia and worked with Tom Hanks there and more recently in Saving Mr. Banks, which I thought was an underrated film.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

He was this kind of comic actor and Philadelphia was one of Tom’s first serious roles, and I remember he would ask me if I brought my script because he just wanted to run his lines between scenes.

I've seen a lot of people get lucky in show business and the danger is if you think you deserve it. And Tom seems to maintain a pretty sustained level of of gratitude.

JON:

I’ve interviewed him a couple of times and hung out with him a little. And he’s a genuinely nice and decent person and unlike most people, actually returns emails.

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

One day [on Saving Mr. Banks] we were watching Emma Thompson [who plays P.L. Travers, author of Mary Poppins], who is just this extraordinary talent. I think it was Tom's first day and Emma had this monologue and it was like watching like one of those mogul skiers. And Tom is right over my shoulder and he goes, “Oh, shit. She’s really good.”

JON:

That’s really funny. He thought he's gonna have to match that as Walt Disney?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Yeah! He was so humble about it.

JON:

I just watched your Funny or Die video parody where you’re “an emotional stuntman” and I thought the whole thing was fucking hilarious. You lampoon Tom Hanks….

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

[I say], “Well, I think Tom's a little too pickled with his own success.” I just love the idea that you can injure yourself emotionally. He couldn't pull off that “Wilson!” line [In Castaway]. He “sprained his soul.”

JON:

Where did you get the idea for doing that?

BRADLEY WHITFORD:

Amy and I wrote it after Funny or Die reached out to us with the idea and gave us a small budget. And then we just did it—all improvised.

JON:

I’d say to my Old Goats readers, now that you’ve gotten this far, spend another 10 minutes on this video. You won’t regret it.

Thanks, Bradley.

I'm so impressed with Brad's sensitivity in "Emotional Stuntman - Bradley Whitford". I'm reminded of the story told of the good ol'days, before CGI....

When filming Midnight Cowboy in 1969, Dustin Hoffman (Ratso Rizzo) couldn't find the right degree of spontaneous energy in the street-crossing scene with the taxicab -- "I'm walkin' here!" The director, John Schlesinger, was about to give up when he remembered a young tennis player from Long Island who could capture the moment perfectly. On the next day, he set up a long-focus shot with John McEnroe limping in the crosswalk in the rumpled white suit with Jon Voight (Joe Buck) - and the rest is history.

Fascinating. For example, the death penalty in politics is reserved for being bad on TV.

And the creative community (hopefully) putting money behind these local races. Thanks.