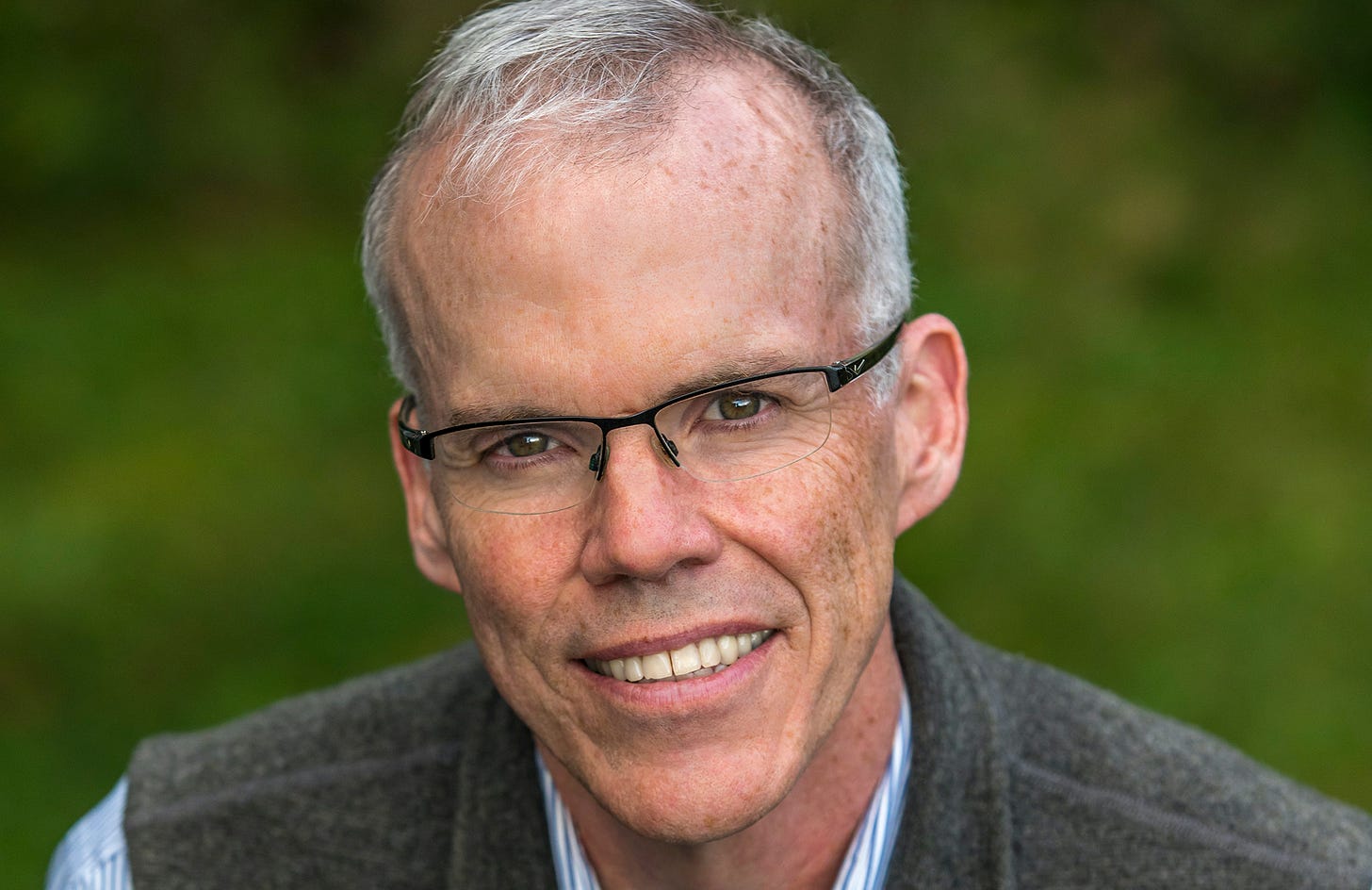

Ruminating with BILL MCKIBBEN

The OG climate activist backs Greta on Glasgow and offers hope of divesting from fossil fuels.

Bill McKibben has become a world-historical figure. He wrote the first book for a general audience on climate change (1989); organized the first global mass movement to protest fossil fuel (2008); and helped inspire hugely successful efforts to force colleges and other institutions to divest from fossil fuel stocks (2012-present). Now he’s launching Third Act, an organization for people over 60 who want to help save the planet. All the while, he has written many thoughtful books and articles on the environment and other subjects and taught at Middlebury College alongside his wife, Sue Halpern, also a talented writer.

I met Bill at the Harvard Crimson in the fall of 1978 when he was a freshman and I was a senior. He went on to be president of the Crimson and we reconnected in New York in the 1980s, when I was at Newsweek and he was at The New Yorker. And Bill has remained a warm and generous person.

JONATHAN ALTER:

How did you move from being a journalist to a journalist/activist?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

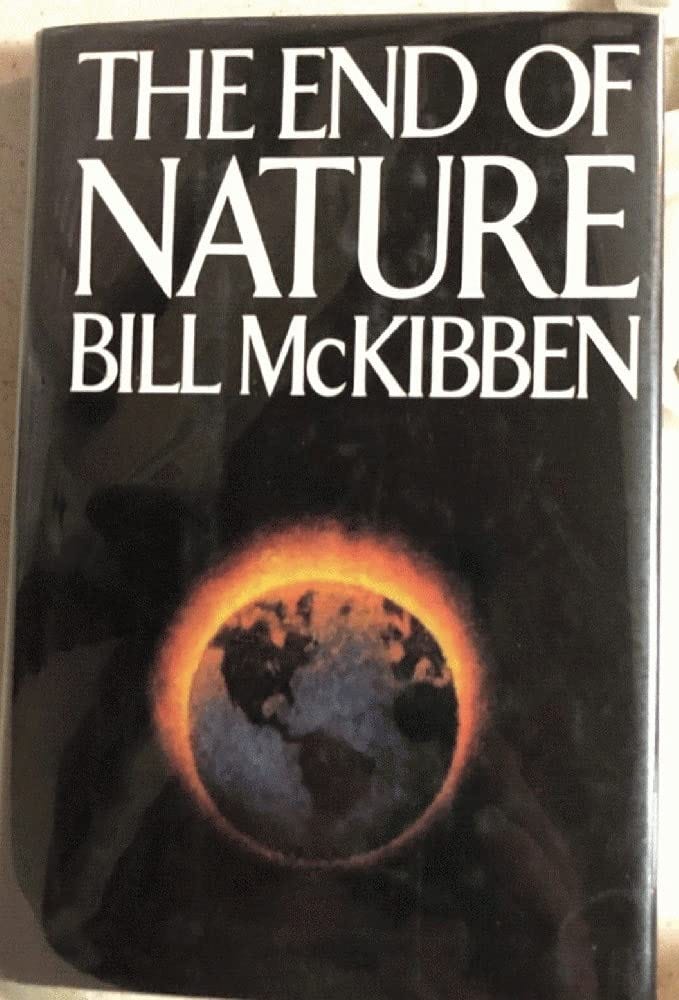

It wasn't particularly conscious. I had been a newspaper guy even before I got to college, and I went straight to The New Yorker afterwards, and then I wrote for Talk of the Town for five years and then I quit when they fired Mr. [William] Shawn and I moved out to the woods and started writing. Within a couple of years, I'd written The End of Nature [1989], which started as more or less a kind of journalistic impulse. I was reading early science and thinking this is the biggest story in the world and it's going to be the biggest story in the world for my whole lifetime. And I had enough journalistic gumption to want to tell it first.

But in the course of writing, it became pretty clear to me that I wasn't objective about the outcome in the way that, at least at the time, we thought journalists were supposed to be. I completely cared whether or not the planet burned up. I didn't want it to. I liked it. And a lot of the book was about the great feeling of sadness about the news of what we were doing. In those days it was more sadness than fear because the actual damage was still abstracted in the future.

“…it became pretty clear to me that I wasn't objective about the outcome in the way that, at least at the time, we thought journalists were supposed to be. I completely cared whether or not the planet burned up. I didn't want it to. I liked it.”

I went on, mostly writing and talking about this for another decade and that's because I thought— incorrectly, naively, without ever really thinking about it— that this was sort of how things work— that if we won the argument, then the political system would start doing what it needed to do. Writers know how to win arguments, so we write more books or articles or compile more evidence, or do more symposiums.

Sometime after the Kyoto conference [1997], it became clear to me that we had completely won the argument. The science was now robust and obvious. We were just losing the fight because the fight actually wasn't about data and reason and evidence and argument. The fight was just about money and power, which is what fights are almost always about, and in order to have any hope of counterbalancing the extraordinary power of the fossil fuel industry, which at the time was by far the richest industry in the world, we'd have to build power some other way. And the only way that history indicated was by building mass movements. So that's what we set out to do.

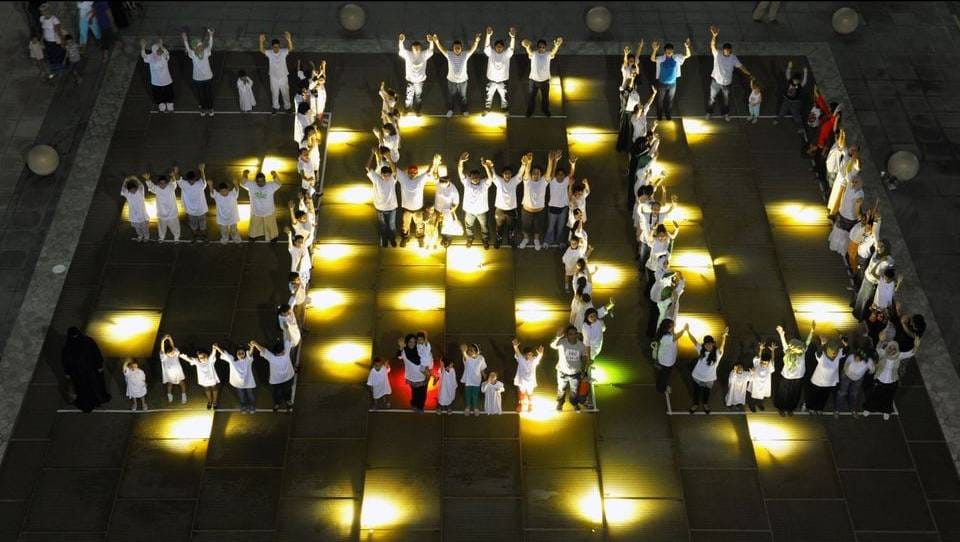

350.org was one of the first iterations of a grassroots global climate movement, and it was effective right away, partly because it was an unfilled ecological niche and partly because of beginner's luck. We soon organized demonstrations in pretty much every country on earth except North Korea. And soon we're helping launch things like the fight against the Keystone pipeline and the divestment movement.

JON:

So let's just talk about 350.org for a second, which you founded in 2008. You have to have real organizational chops to do that. Where did you get those? And who were your colleagues at first?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

We started in the 2008 primaries by demanding that people sign on to this idea of 80 percent cuts in carbon emissions by 2050, which now is less than we need, but was very, very radical then. That spring, we coordinated on the same day about 1500 simultaneous rallies around the country. And within the next 10 days, both Obama and Hillary Clinton [still battling for the Democratic nomination] had signed on to this 80 percent target. So, having figured out a somewhat effective method of organzing widely distributed events, we decided to try it globally. Because they don't call it global warming for nothing."

The key colleagues that I started it with were seven undergraduates at Middlebury College. And they had no more experience than I did, but there were seven of them and there are seven continents. So they each one took one. We were making it up as we went along but I think we were pretty lucky in that the landscape was quickly changing. Facebook and Twitter weren't quite real yet and our killer app was at first something called Flickr that let people share photos.

The first big action we did was right before Copenhagen [COP15, the 2009 global climate conference], and we managed to coordinate simultaneously about 5200 demonstrations in 181 countries. Now at first most of them were small—about 100, 200, 400, 700 people. It took us seven years to reach the point where we could get 400,000 people in the streets of New York, but the internet allowed us to do all this and we told everybody to send the pictures back in real time as they were doing it.

And there was almost enough Internet access to let everybody—all of us were volunteers— take part but in some places it was hard. I remember a 17-year-old girl who was running our operation in Ethiopia, where they had 10,000 kids out in the street of Addis Ababa. The Internet wasn't working and she couldn’t get her pictures out to the press. So I said, go to the lobby of the Intercontinental— the one Western hotel— and she calls back and says they won't let me in. I said, ‘Stand there and find a white lady going in and hand her your phone and tell her to press the button.’ And that's eventually what happened.

I'd always been told that environmentalists were rich white people and that if you didn't know where your next meal was coming from, you wouldn't be an environmentalist. Almost everyone we were working with around the world was poor, Black, brown, Asian, young, because that's what almost everybody on Earth is. And they were exactly as interested in all of this as we were— maybe more so because the world bears down hard on them. Our theories of change were pretty simple and from then on they mostly involved picking a lot of fights, some of which really panned out like this divestment thing and the Keystone thing.

The sequence of [the Keystone pipeline battle] was fascinating. Indigenous groups have been fighting it for a while, mostly in Canada, and some farmers and ranchers in Nebraska. This was 2011. And I heard about it and realized that because of this weird old statute, when you build a piece of infrastructure that crosses the U.S. border, it requires the President to sign off on it.

Obama was talking big about climate but not doing anything about it. We realized that we can legitimately demand action and he'll have to answer one way or the other. So in the summer of 2011 we coordinated with a bunch of different people and I wrote a letter asking people to come to D.C. to get arrested. And it turned into the biggest civil disobedience action about anything in this country in a long time—1,254 people went to jail over the course of two weeks. I spent three days in central cellblock in D.C.

At the beginning, it just seemed completely hopeless. Big Oil had never lost a fight like this. National Journal did a poll of energy insiders in D.C. and I think 91 percent of them said that the company would have their permit for [Keystone] by the end of 2011. But then all these [protesters] went to jail and it turned out that there were tons of people who wanted someplace to take a stand around climate change—and not just talk about it, but demand action. By November, Obama had put a moratorium on a decision and that held for a few years until—after people just kept organizing every place—he finally put the kibosh on the thing. It came back to life, sort of, under Trump but by this time the economic case for it was getting a little shaky. There was no way Biden would go back to it. It’s dead for good. But he has approved--implicitly, anyway--the Line 3 pipelineline across Minnesota. Which is crazy, because it's a perfect doppelganger for Keystone, same size and carrying the same crud.

JON:

Were you guys out there in Minnesota?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Yeah, people are fighting real hard. But we couldn’t get out during the pandemic and now oil is flowing through it. The Keystone thing was important because it showed people you can fight Big Oil and then people started taking on everything. So every pipeline, coal terminal, fracking well—it all gets fought now. We don't win all the time but it's amazing how often you win when you actually fight. And in every case, we delay people and cost them money, and so it turned out to have been a very useful thing to have done.

“We don't win all the time but it's amazing how often you win when you actually fight.”

JON:

And divestment?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

In 2012, Naomi Klein and I were talking because we read the same report from this little think tank in London saying, “Look, the fossil fuel oil companies have five times as much oil in their reserves as scientists say we could safely burn. This is what they've told their shareholders they're going to dig up and sell. This is their business plan. If they carry it out, then the world is wrecked.” So having read that, it looks like OK, these are rogue companies. If you think about it this way, they're not respectable parts of the business universe. What do we do with rogue companies?

Well, you and I had both been in college during the divestment campaigns around apartheid [in South Africa]. And so that's what we hearkened back to and and we did a big series of events that autumn [2012] around the country—-27 cities in 30 days or something. This was enough to get this ball rolling and pretty soon it was just like Tom Sawyer and the whitewashed fence. People were just picking this up at campuses and churches and pension funds and figuring out how to run with it. It was tactically useful because most people aren't really near an oil well or a coal mine but everybody's adjacent to a pot of money someplace.

JON:

All of this seems more important in historical terms than Occupy Wall Street, which gave us the concept of the 99 percent and the 1 percent but not much more.

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I'm not sure I agree, I think Occupy Wall Street not only had that rhetorical power, but it also it also really set things up for Bernie to run in 2016, which I think turned out to have been quite a watershed moment in recent political history. I got to introduce him when he announced on the shores of Lake Champlain— me and Ben and Jerry. Bernie’s at 2 percent in the polls, and within six weeks, he's at 40 percent. All of a sudden, this centrist Washington idea, which had lasted since Reagan and was certainly very strong in the Clinton and Obama years—the idea that this was a center-right country—isn’t working. And so now you've got Joe Biden trying to be LBJ again.

JON:

Divestment started in 2012 at tiny Unity College in Maine. I learned about Unity when researching my Carter book, which opens with Carter putting solar panels on the roof of the White House. After Reagan took them down, Unity got some to display.

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I tried to bring them down for Obama to use. [He later put up newer solar panels}. Yep, [divestment] started with Unity and a smattering of other colleges and the World Council of Churches and within a year or so, the Rockefeller family divested their charitable fortunes. That was obviously significant since this was the first great oil fortune in the world now declaring that it was immoral and fiscally unwise to be invested in oil. And that really helped. We did the same kind of tour around Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and got big campaigns going there. And it just kept building and building to the point where we're about $40 trillion in endowments [divested] and we finally got Harvard this year—grudgingly and ungracefully, but they finally did it. There were probably 10,000 of these fights around the world and each one produced a whole crop of people who knew how to be activists. Many of the people who formed the Sunrise Movement, which produced the Green New Deal, had cut their teeth doing divestment in college.

JON:

So in the streets in Glasgow, that was a kind of consortium of many different groups?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

It was largely organized by the wonderful Fridays for the Future movement that sort of sprung out of Greta [Thunberg’s] work. And there are now thousands of Gretas around the world. I love her and think she's one of the greatest activists—a master of the politics of gesture. A remarkable human being. But she'd be the first to say the really good news is that there's now 10,000 like me, and 10 million followers.

When I started 350.org with those college kids there wasn't quite as much youth climate activism and you still heard some people saying, “Oh, kids today, you know, they're apathetic or whatever.” That was nonsense then, and it's completely gone now.

JON:

Greta called Glasgow “the blah, blah, blah conference.” Do you agree with that?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Yeah. All the drama went out of the room when it was clear Biden couldn’t show up with the full Build Back Better legislation in his back pocket, toss it on the table and say, “Match this, amigos.” Then Joe Manchin strips the clean energy pricing plan out of it, and he holds the whole thing up so it can't pass just in time [for Glasgow]. So Biden shows up there [at COP26] with nothing. Joe Manchin has taken more money from the fossil fuel industry than anybody else in D.C. in the last cycle and the fossil fuel industry got their money's worth—1000 times over. It’s the best return on investment that these guys ever made.

“All the drama went out of the room when it was clear Biden couldn’t show up with the full Build Back Better legislation in his back pocket, toss it on the table and say, ‘Match this, amigos.’”

I think it's possible that [the COP conference approach] is beginning to reach the end of its usefulness, because there are so many illiberal governments around the world now that aren't taking useful part in the whole thing. That was the U.S. under Trump. But now even with Trump gone, there’s Bolsonaro [Brazil], Putin [Russia], Orban [Hungary], Modi in India. Xi in China. There's really no way these guys aren’t making their own national calculations about what to do.

JON:

I wanted Biden to appoint Rahm Emanuel as ambassador to Brazil—not Japan—so he could be up in Bolsonaro’s grill about destroying the Amazon. Rahm preferred Tokyo.

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Bolsonaro would be hard. Those guys are truly thugs. Not in the Trump sense of the word but in the head off with a machete sense of the word. As long as he’s there, [Brazil’s promises on climate change] are all completely meaningless. There's no way to really pursue it.

JON:

How about applying sanctions?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

He's a madman. He's one of these guys who would like sanctions. He's desperately unpopular and if they can ever make him hold an election next year, he'll get beaten badly. But he's already angling to preempt the election.

JON:

So with all of these authoritarian governments, politics isn’t working.

BILL MCKIBBEN:

If you think about the real debate that's going on, it's not really Democrats versus Republicans and industrialists versus environmentalists, America versus China and on and on. The real negotiation is just between human beings and physics. And so it's a difficult negotiation because physics is completely uninterested in compromise, in the same way that the COVID molecule was uninterested in compromise.

“…the real debate that's going on, it's not really Democrats versus Republicans and industrialists versus environmentalists, America versus China and on and on. The real negotiation is just between human beings and physics.”

JON:

So the action is moving to the private sector?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I think that there are two levers to pull big enough to matter. One of the levers is marked politics and the other is marked money. We've pulled the politics one almost to the ground and I don't think there's much play left in it. The money one we’re only just getting going—taking on the banks and stuff.

When the pandemic hit, my last trip out before lockdown was getting arrested in Washington, at the Chase branch nearest the Capitol. This campaign against Chase continued and we won some victories along the way, but activism is difficult to carry out on Zoom. So, it's only now that things are getting fully back in gear.

JON:

One of the most interesting things I read out of Glasgow was in this publication called Climate and Capital Media that my old colleague Peter McKillop from Newsweek started and it was about something called GFANZ [Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero], run by a guy named Mark Carney. Are all of these banks good for the $100 trillion necessary to get us to Net Zero?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Banks are just tallying up how much money all them have. But they haven't committed to doing anything and it's not clear whether it's going to be useful or just another greenwashing effort [creating false impression about environmental responsibility]. What we really need them to do right now is stop lending money to the fossil fuel industry. They don't want to because it's a reasonably large part of their deal book and so they're casting about for ways to make a lot of noise about Net Zero by 2050, but it's not at all clear what it means.

JON:

So you think they're not on the level?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I think they're closer than they were a few years ago because there’s a balance of pain.

JON:

How about going after them through insurance?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

We are taking on the insurance industry in a big way. The day before I left for Glasgow, we were out in the street in Boston, outside Liberty Mutual. The insurance industry has two problems. Does the insurance industry knows better? They have all the actuarial data to indicate the approaching end of the world but they continue to invest their huge amounts of surplus capital in fossil fuel. And to be even more ridiculous, they continue to underwrite fossil fuel expansion projects. If you have a pipeline that you want to build, you can't build it unless you can get one of about 10 companies to give you insurance.

These guys keep doing that for trifling sums. Remember the whole thing about capitalists [who] will sell you the rope with which to hang themselves.

JON:

How is that going with people like Larry Fink of Black Rock and the big pension funds?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

We just need to be able to bring more pressure to bear and we will over time.

We’re backing up young people who are demanding that banks stop lending money to the fossil fuel industry. This is a perfect case of where older people should be helping out. Banks fear 19-year-olds because they know that wherever you get your first credit card from, you'll stay [with that bank] for a long time. But banks are well aware that people over the age of 60 have about 70 percent of the financial assets in America, contrasted with about 5 percent for millennials, This is a place where intergenerational power could be useful.

JON:

Okay, so let's talk about Third Act. What is it?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

We're just very, very early days but we’re trying to work across issues. The other thing we're really working on beyond the climate is the political climate and we’re initially giving a lot of attention to voter suppression and voting rights. There's this idea that people become more conservative as they age, and there's a certain amount of evidence for it. We can't let that happen just because of the extraordinary power of 10,000 people turning 60 every day, which is more people that are born every day in this country.

For a very long time, this generation— Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation—are going to occupy a position where they can block change if they want to. They vote in huge numbers and they have most of the money.

“For a very long time, this generation— Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation—are going to occupy a position where they can block change if they want to. They vote in huge numbers and they have most of the money.”

So this is a real effort to start shifting their generational perception. The logic of it is that those of us who are this age either participated in or bore witness to really profound political, cultural, and social transformation. We have a memory of it almost in our bones. If our second act was, as a whole, somewhat more devoted perhaps to consumerism than citizenship, now we emerge with lots of skills, resources, grandkids— ready to try to somehow build a legacy that's not “We left the world a lot worse than we found it.” That’s what we're aiming for at the moment. I think it'll be intriguing to see if we can do mass organizing.

JON:

I think it's a really exciting idea. I didn't know anything about it until very recently. But I think you need some refinement on what people can do—some very specific commitments for Third Act people to make.

For instance, I’ve always despised leaf blowers but I've never done anything about it. Let’s say I got something from Third Act that said, “Will you commit to not allowing any two stroke leaf blowers where you live?” I’d do it. I read on Jim Fallows’ Substack newsletter that leaf blowers emit twice as much as cars in California. That amazed me.

Don’t you think part of it is an education function for older people who don't know a lot of stuff that younger people completely understand?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

There's always this tension between people doing things as individuals and people doing things together. And it's a strong tension that is irresolvable in certain ways. But I must say, the deeper we get into the climate crisis, the harder it is to make a case that you can significantly influence the math, one action at a time. I mean, my house is covered with solar panels, I'm proud of them, but I try not to fool myself [by thinking] “So that's how we're going to do this.” At this point, one Tesla at a time is not going to cut it.

JON:

But even if the problem with methane is mostly corporate agriculture, isn’t it worthwhile to do what you can? People our age are so despondent over what’s happened to the country that they’re paralyzed. I’ve got this line my family’s getting tired of, but I still like it: “It’s time to stop wringing our hands and start ringing doorbells.”

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I'm stealing it. You know, it's funny, I was thinking about you the other day because I'm finishing up this book set in the Carter period that you were writing about most recently, and your book is very helpful. Mine is almost a memoir of looking back. The title is The Flag, the Cross and the Station Wagon and it’s about an American who looks back at his suburban boyhood and wonders what the hell happened. And you were writing about what turned out to be the hinge years. That fateful choice was the election of Ronald Reagan.

JON:

I was amazed to learn in my research that Carter planned to begin addressing global warming—which he had first gotten interested in by reading a scientific journal in 1974—had he been reelected.

BILL MCKIBBEN:

I wrote the story that night for the Crimson, sitting in the newsroom with the typewriter and getting drunker and drunker and writing hundreds of column inches. And then I went away drunk and sad and staggered back two days later and wrote a long, full-page editorial piece, just saying this is not the small setback people think. The wave is breaking now.

JON:

That turned out to be rather prescient. And in 1992, you were again when you wrote a book called The Age of Missing Information about how all the new TV channels—all the choice—was stultifying and a waste of time. But that was before the Internet. Now, that screen can be an actual menace, right?

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Absolutely. And the Right figured out how to weaponize it. Every place in the world that Rupert Murdoch has touched, he has wrecked. Though I'm grateful for the fact that the Internet let us organize 350.org, clearly on balance, it wasn’t worth any of it. In exactly the same way that the fossil fuel industry is willing to wreck the planet in order to keep its business model going, it's entirely clear that Facebook [Meta] is willing to wreck democracies everywhere in order to keep their stupid business model going.

JON:

Two years ago, you wrote Falter, which contained pretty dark material as well as a little hopeful stuff. But then you wrote this piece in September for your Substack newsletter [The Crucial Years] that was more upbeat. So where are you on the hope meter?

“We’re obviously not going to stop climate change. That's not on the menu. The question is, can we stop it short of the place where it cuts civilization off at the knees? That's very much an open question.”

BILL MCKIBBEN:

We’re obviously not going to stop climate change. That's not on the menu. The question is, can we stop it short of the place where it cuts civilization off at the knees? That's very much an open question. We don't know the answer to it. It will take everything we've got. The only thing we have going for us is that the scientists and engineers have reduced the cost of renewable energy to the point where it's the cheapest power on earth. So there's no longer really a technical or financial obstacle to doing what needs to be done. There's just this toxic combination of vested interests and inertia that may well prevent us from doing enough.

The reason this is so difficult is our political systems are not set up for timed tests. All the political issues we’ve grown up with allowed time to see how policies played out. But climate change isn't like that. If we melt the Arctic, nobody has an Arctic refreezing plan to put into place.

JON:

Thanks, Bill.

Note: I will not be posting next Thursday, November 25th for a good reason—Happy Thanksgiving!