Ruminating with BILL FOEGE

The public health legend on Trump’s “unconscionable” Covid response, and how he designed the program that eradicated smallpox, the most deadly scourge in human history.

I first interviewed Dr. William Foege, now 85, on the phone while working on my Jimmy Carter biography but we didn’t meet until earlier this month, when we both attended the Carter’s 75th wedding anniversary celebration in Plains, Georgia. Bill was raised in Iowa and Washington State, where at age 15, he was in a body cast for months while healing from a bone and muscle disease related to his exceptional height of 6’7”. As a boy, he was inspired by the story of Dr. Albert Schweitzer, the French polymath philosopher and humanitarian who built hospitals in Africa.

After earning his MD at the University of Washington Medical School, Bill joined the United States Public Health Service as an epidemiologist and embarked on perhaps the most storied career of any American in public health. After historic work eradicating smallpox while working for the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Nigeria and the World Health Organization (WHO) in India, he ran—and transformed— the CDC in the Carter Administration. In 1986, he became executive director of the Atlanta-based Carter Center, where he helped make the former president’s organization a leader in global health.

President Obama awarded Bill the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

JON:

Thanks for doing this, Bill.

Last fall, seven months into the Covid crisis, you wrote a letter to Robert Redfield, Trump’s director of the CDC.

BILL FOEGE:

One night, I just had enough. I was so discouraged and disgusted that he was not standing up to the Trump Administration. But I never intended that letter to be public. It leaked out of Redfield’s office.

JON:

You wrote that the CDC’s reputation had gone from “gold” to “tarnished brass.” What did you mean?

BILL FOEGE:

I sometimes talk to students about “the Tragedy and Triumph of Coronavirus.” The tragedy is that since the time of Louis Pasteur, we have been learning lessons on how to control infectious diseases— and every one of them was violated by the Trump Administration.

Number one: cause and effect. In his book, A Short History of Time, Stephen Hawking writes that the history of science is the gradual realization that things do not happen in an arbitrary fashion. It's a cause-and-effect world. And instead, what did we get from President Trump? He said, “This will disappear like magic.”

The second lesson is you have to know the truth about things. And we could not tell what the truth was. At one press conference, you'd hear one thing and then another. We were always in the dark.

The third lesson is that you have to look at this from a global perspective: we’re not going to be normal until every country is normal. So the whole thing was just unconscionable. Lessons aren’t worth anything if they aren’t learned.

Okay, so what's the Triumph? The vaccine. As bad as this virus is, it can't stand up to the science. And so then you ask, “How could the same people in power both inhibit public health and produce a vaccine?” I don't know the answer. But it could be as simple as, it's very easy to make public health proclamations. But it’s very hard to say, “I know how to make a vaccine.” So they put up money for the drug companies and the NIH, and then they got out of the way. And that's how the same people could do such a good job on the one hand, and such a terrible job on the other.

“The tragedy is that since the time of Louis Pasteur, we have been learning lessons on how to control infectious diseases— and every one of them was violated by the Trump Administration.”

JON:

Historians are going to have a very interesting time with this. Tony Fauci continues to look like he did the right thing. He didn't quit, but he also didn't stop telling the truth. Dr. Deborah Birx— how do you assess her performance?

BILL FOEGE:

She said, I don't trust the CDC. To have a public health person on the [Covid] task force say she no longer trusted the CDC. Unbelievable. And Senator Susan Collins said the same thing. I noted the irony of a politician telling us who we can trust.

JON:

You recently quoted Primo Levi saying if you know how to prevent torture and don’t, you’re a torturer, too.

BILL FOEGE:

Rabbi Heschel was correct when he said, There are some people who are guilty, but we’re all responsible.

JON:

For a religious Lutheran, you know your Jewish philosophers. But some are more responsible than others, right?

BILL FOEGE:

A few years ago, I wrote a letter to the governor of Georgia [Nathan Deal] saying that he seemed to be reading a new edition of Matthew 25: When do I see you sick and not provide Medicaid? One has to be very careful not to come across as righteous in these things, but when you don’t expand Medicaid, you’ve made a decision to hurt people.

“One has to be very careful not to come across as righteous in these things, but when you don’t expand Medicaid, you’ve made a decision to hurt people.”

JON:

Especially when —under the Obamacare formula —that expansion costs the taxpayers of your state exactly nothing. That’s crazy but what’s going on with the governors of Tennessee and other states—and on Fox—is crazier. Almost all the people dying are unvaccinated, so to be out there with a public message that gives aid and comfort to the anti-vaxxers is, to me, beyond irresponsible. These people have blood on their hands.

BILL FOEGE:

I agree. But I don’t like the approach that says we’re two nations—vaccinated and unvaccinated—because that just asks for political division. I do like the phrase that the pandemic in the United States is over—except for the unvaccinated.

JON:

When you were head of the CDC [1977-1983] we made huge strides in public health that we don’t appreciate today. Rosalynn Carter was first lady and she got together with Betty Bumpers [wife of Arkansas Sen. Dale Bumpers) and with great help from you, they convinced state legislatures to require vaccinations for kids to go to school. Kids would start crying when they saw the first lady because they thought she was going to give them a shot. I sure hope we can return to vaccine passports.

“I don’t like the approach that says we’re two nations—vaccinated and unvaccinated—because that just asks for political division. I do like the phrase that the pandemic in the United States is over—except for the unvaccinated. “

BILL FOEGE:

I set a goal of immunizing 95 percent [of school-age children] and was told it was impossible, but when I changed the job description [of the government official who would implement it]—when that was specifically what his job required—he got it done. The next question was could we do something about transmission of measles, which is as contagious as coronavirus.

JON:

When I was a kid, I and practically everyone I knew had measles, but we didn’t realize how dangerous it could be.

BILL FOEGE:

We were told we shouldn’t even try to stop it because we’d fail and it would ruin CDC’s reputation. But surveillance worked. After one outbreak, we traced it to Disneyland and because you could see the rash on those infected we realized [it was being spread by] Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck or someone with a costume on.

By the mid-80s we had our first week without a case, then our first month and finally it became front-page news when there was a new case. With the first dose, they got to 95 percent protected. Then with the second dose, you protect [almost all of that remaining 5 percent] and you came close to everyone being immune.

JON:

We’re at almost 66 percent [partially vaccinated for those 12 and over] for Covid, a more fatal disease. How high are we going to be able to go, given the blood-soaked opposition?

BILL FOEGE:

We have no alternative but to keep going til we get vaccination levels for Covid that are as high as what we had for measles. It’s an education process. A grassroots approach.

JON:

Wasn’t local information from trusted local sources the key to [nearly eradicating] Guinea worm and [eradicating] smallpox? Can you explain how surveillance [also known as contact tracing] and what you pioneered—“ring immunization”—interrupting the chain of transmission with targeted local immunizations?

Is that basically how you eradicated the greatest scourge in human history—a disease that killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone?

BILL FOEGE:

First of all, you are being too generous and that makes me uncomfortable. I am sensitive to various attempts to rewrite history on smallpox eradication. This was a collaborative effort.

It was a change in perspective. For 150 years people had been thinking in terms of herd immunity. But that's just a useless concept from my point of view. They always said, if you got to 80 percent vaccination with smallpox, you would get herd immunity. And so repeatedly, India would have smallpox campaigns, outsiders would come advise them, and then they would come in later and do an evaluation. And they always found that they had reached 80 percent, though when they started looking person by person, it was about 60 percent.

JON:

So after running a CDC smallpox program in Nigeria in the sixties, and getting some good advice from a Russian epidemiologist named Viktor Zhdanov, you go to India in the early seventies.

BILL FOEGE:

At first the news on vaccinations was terrible. [The authorities] said, 80 percent isn't working—you have to increase your target to 100 percent. And of course if you can’t reach 80 percent, that makes no sense whatsoever. And so we came in and totally changed things and said, “Forget about herd immunity. We’re going to concentrate on finding where the virus is, and then vaccinate just those people [in a ring] around it.”

“Forget about herd immunity. We’re going to concentrate on finding where the virus is, and then vaccinate just those people [in a ring] around it.”

JON:

That was revolutionary.

BILL FOEGE:

If the government in India approves of something, you can make it work. Their trains run on time; they have inherited from the British a certain system of government that involves filling out forms for every activity. So when [the bureaucracy] gets a directive and you get inside the system, they can make things happen.

Towards the end, we thought we were going to lose the government because the international press—which had come to cover nuclear testing—reported that smallpox had been worse than the year before. They didn’t understand that it only looked worse because our surveillance system was working. It embarrassed the government. And so the Minister of Health of Bihar said, We're going to stop this and go back to mass vaccination.

And that's the story of my book—how the villagers finally convinced the minister that what we were doing was correct. It was just a last minute decision that saved the day.

JON:

A decision that would eventually save millions of lives from dozens of infectious diseases.

So to put it in more simple terms that a lot of people will now understand: you believe in contact tracing, not herd immunity.

BILL FOEGE:

Exactly, exactly. And so the argument against what we were doing is that you have a whole cohort of children being born every month, unprotected. And once smallpox gets to that group, you're going to have a an epidemic or pandemic. And we said, yes, that's why we have to hurry and finish what we're doing.

JON:

This is amazing. You said that this new approach was launched in 1973. And my understanding is by 1975, smallpox was close to having been eradicated worldwide. Right?

BILL FOEGE:

It's even more dramatic. In May of 1974, we had 1500 new cases a day in Bihar. Twelve months later, the entire country of India was free of smallpox. That’s twelve months of the most exciting health work that we've ever seen.

JON:

You helped complete an effort that began in the 18th Century with Edward Jenner using cowpox in England. It’s odd to hear conservatives decry mandatory Covid vaccination in the military when that’s what George Washington did with smallpox to save the Continental Army and win the Revolutionary War.

BILL FOEGE:

Smallpox was so common then that Voltaire estimated that 60 percent of all children in Europe would get it. The Continental Army was so decimated by smallpox that it lost the Battle of Quebec in 1775, which meant that Canada would not be part of the United States. And that's when George Washington realized, “I've got to do something about this.” His greatest tactical decision was to [innoculate] American troops. And they did it very quietly, because they were sure that the British would try to attack while lots of soldiers were down with mild smallpox.

JON:

And European settlers spread it to Native Americans.

BILL FOEGE:

Yes, and it spread much faster once the tribes got horses.

JON:

Washington believed in ring inoculation. If we don't adapt those specific surveillance and ring vaccination programs, we're going to be dealing with this for half a century, right?

BILL FOEGE:

That is correct.

JON:

How about another factor—cash. Wasn’t money for villagers extraordinarily important in both smallpox and in Guinea worm? You and Jimmy Carter don't like to say this, but isn't it true that the $100 you paid village elders to identify the presence of Guinea Worm in their villages and to supervise the use of the water filters etc. was very important?

BILL FOEGE:

Sure. You're paying for a service, but it's not just that you're giving money. And in India, if we had paid rewards, we would have gone broke. But as we went along, we started out with small rewards, 10 rupees, increased it until it went up to $1,000. And we did surveys that found that more people in India knew about the smallpox reward than knew the name of the prime minister.

JON:

You know, Amazon earned billions of dollars in profits in the last 18 months. They have a problem with unvaccinated people in fulfillment centers in red states. They should just pay them to get vaccinated. Everyone has their price.

BILL FOEGE:

The [bigger] answer is surveillance and I’ve been very disappointed in contact tracing in this country. They come up with all kinds of excuses about why it’s too hard to do.

We did it with smallpox and that was before we had smart phones or computers. I’m mystified by why we can’t do that.

“…I’ve been very disappointed in contact tracing in this country. They come up with all kinds of excuses about why it’s too hard to do. We did it with smallpox and that was before we had smart phones or computers. I’m mystified by why we can’t do that.”

JON:

Any theories as to why?

BILL FOEGE:

I think the public health [workers] were so concerned about Trump’s approach that they lost some of their abilities. Now it’s time to build them up again and show them what they can do. I’m hopeful that with the new money for public health and the hiring of new people, we can get back to an infrastructure that can do these things.

JON:

Pfizer is trying to get approval for a booster shot, and the government is pushing back hard. What do you make of that?

BILL FOEGE:

Given the “breakthrough” cases [where vaccinated people are getting infected, especially with the Delta variant], I can see why Pfizer is pushing it. On the other hand, there is so much need for that vaccine for first doses that I think the world would be better served by using all of the [available] vaccine to get initial immunity. The U.S. will never go back to normal until Uruguay and Sudan and Zimbabwe go back to normal.

JON:

Are you as suspicious as I am of drug companies that get so much more for booster shots at home than for dosages abroad?

BILL FOEGE:

I end up upset when drug companies try to make money beyond what is reasonable. But my experience [with the drug companies] has been so good on global health, starting with Merck and their provision of over five billion free treatments of Mectizan [a drug that has dramatically reduced river blindness]. And what is now GlaxoSmithKline has done the same for elephantiasis [a devastating swelling of limbs] with Albendazole.

JON:

Jimmy Carter’s connections with the enlightened CEOs of those companies and with the dictators [for which he was criticized] really helped.

BILL FOEGE:

If I go to Africa, I might be able to meet with minister of health but that doesn’t mean much. Carter meets with the head of state and says, this is what we and you can do with Guinea worm, river blindness or elephantiasis. And then the minister of finance becomes interested, and that’s where the power is.

JON:

Now that he’s too old to travel, who will play that role?

BILL FOEGE:

I don’t know, but someone will. Gro Brundtland [former prime minister of Norway and former longtime head of the World Health Organization] already has. And I sure would like to see Obama do that.

JON:

The Gateses?

BILL FOEGE:

Yes, of course. I often say that when the history of global health is written, we will find that the tipping point was about the year 2000, when the Gates family became interested in global health. Before that, there was very little interest. The Carters and the Gateses—those two families have changed everything.

JON:

Are you concerned about the impact of the Gates divorce on their foundation?

BILL FOEGE:

I have no inside knowledge but I think they will figure out how to keep the foundation as productive as it has been. They’ve given over $50 billion to global health in the last two decades and that’s made all the difference.

JON:

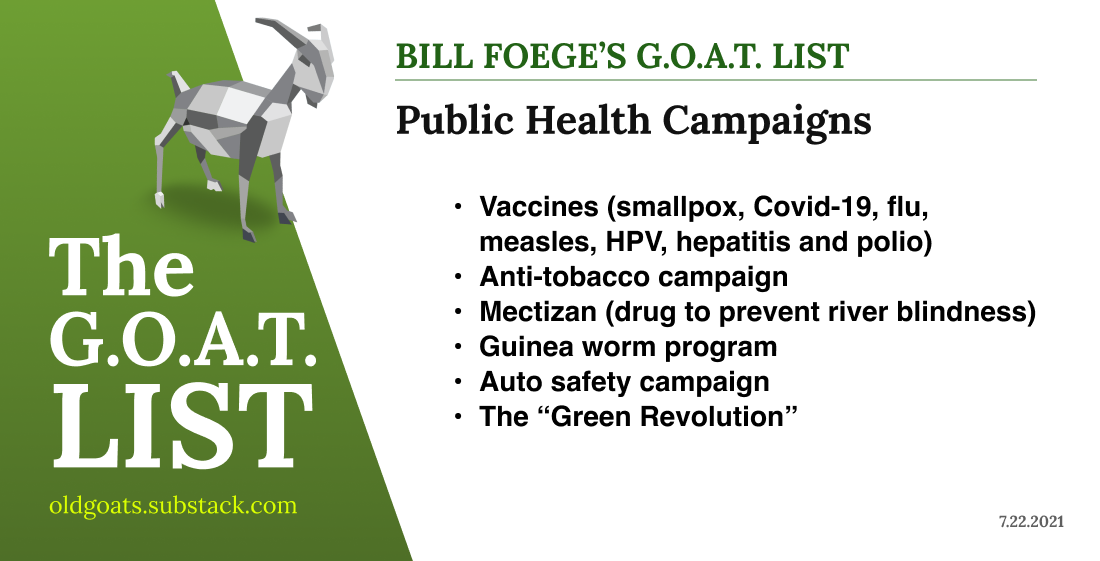

More people need to appreciate what "public health" means.

BILL FOEGE:

The major benefit of public health in the past hundred years is that it has put science, knowledge and technology into the hands of individuals, even when they don’t trust science. The ability of individuals to get vaccines, stop smoking, diet, reduce alcohol intake, wear seat belts, helmets, drink safe water, eat safe foods, use sun block, monitor their blood pressure and pulse, track exercise patterns has led to better-informed daily decisions by millions of people. It is an awesome tapestry of consequential science practiced by believers and non-believers alike.

JON:

Let’s hope we’ve learned a lesson about cutting funding for public health after memories fade. And there should be a new generation who will, because of this disruption in their lives, be passionately committed to public health.

BILL FOEGE:

Yes. That will be very exciting.

JON:

Thanks, Bill.