No, This isn't Saigon 1975

The reports of major political and strategic fallout from the fall of Kabul are greatly exaggerated

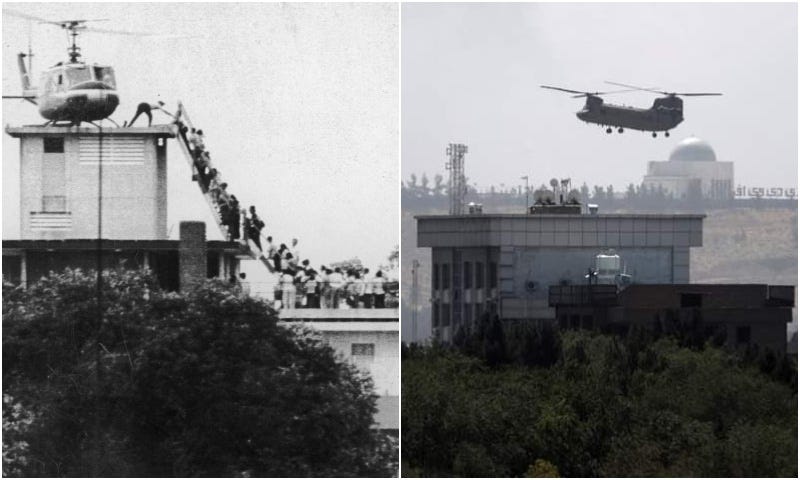

How many times in the last week did you hear about—or see an image of—the last helicopter lifting off the U.S. embassy compound in Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War?

The press seemed almost disappointed that it lacked a shot of an American helicopter lifting off from the airport in Kabul, with desperate Afghans clinging to the bottom. It made due with an image of Afghan civilians running down a runway as a C-17 lifted off.

The historical analogy between 1975 in Saigon and 2021 in Kabul was just close enough to be dangerous to clear thinking.

In both cases, a long war came to an ignominious end for the United States, with poor planning for the evacuation of civilians who had helped the U.S. In both cases, the U.S. was betraying thousands of interpreters and others who helped us. And in both cases, Republican hawks (and a few Democrats) felt the evacuation dealt a grievous blow to American strategic interests and the credibility of the United States to stand up for our friends.

But historical analogies can be tricky. The differences between the two events—separated by 46 years—may be as significant on the ground as the similarities.

In Vietnam, tens of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians were evacuated in the weeks before the North Vietnamese army took Saigon; in Afghanistan, the vast bulk of those evacuations—if they can be completed—will take place after the fall of Kabul. In Vietnam, the communist victors wouldn’t let any civilians leave; in Afghanistan, the Taliban victors are at least claiming that they will.

In Vietnam, tens of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians were evacuated in the weeks before the North Vietnamese army took Saigon; in Afghanistan, the vast bulk of those evacuations—if they can be completed—will take place after the fall of Kabul.

I once took a class at the Kennedy School of Government from two legendary Harvard professors, Richard E. Neustadt and Ernest R. May, entitled: “The Uses and Misuses of History.” (Book: Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision-Makers). Much of the class was on the latter. While “thinking in time,” as the professors put it, is an important dimension of sophisticated policymaking, historical analogies are often used crudely and without regard to the fundamental differences between disparate global events.

The classic example is “Munich”—shorthand for Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Adolf Hitler when they met in Munich in 1938. Throughout much of the Vietnam War, President Johnson was haunted by Munich—by the idea that if he withdrew from Vietnam, he would be appeasing the communists and weakening the United States. President Nixon could have easily ended the war in 1969. “He could have just blamed the whole thing on us,” LBJ’s defense secretary, Robert S. McNamara, once told me. Instead, Nixon embraced the same Munich frame, once saying that if the U.S. left Vietnam, it would be reduced to being “a helpless, pitiful giant.”

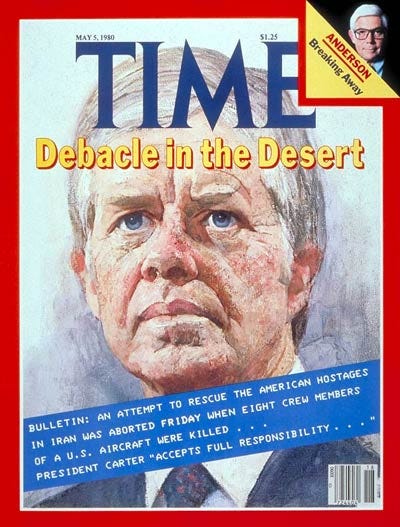

Today’s conservatives are employing another analogy: Jimmy Carter and the hostages. A Wall Street Journal editorial writer, William McGurn, argued this week that “For President Biden and his team, the analogies to President Carter and the Iranian hostage crisis might be even more unsettling than the obvious parallels to the 1975 fall of Saigon they are working so hard to deny.” Biden, McGurn concludes, looks “weak and inept.”

Let’s stipulate “inept.” Even if the Taliban allow a massive U.S. airlift evacuation of Afghan civilians over the next few weeks, historians will puzzle over how the Biden Administration failed to grasp the gravity of the military and political decay inside the Kabul government, failed to cut red tape on visa applications, and failed to develop a contingency plan for avoiding a chaotic retreat.

With Biden, it’s always personal.

We now know that the intelligence on the weakness of the Afghan army was largely accurate. So why the epic fail? My guess is that it involves Biden’s personal relationship with former Afghan president Ashraf Ghani.

In 2011, I was sitting in Vice President Biden’s office and he let me overhear his conversation with then-Iraqi President Jalal Talabani. It was a warm and familiar conversation based on trust. A decade later, it seems logical to me that Ghani made personal assurances to Biden that were worthless, and the President let those assurances take precedence over the intelligence. With Biden, it’s always personal.

But that ineptitude is a tactical matter. On the strategic question—should we stay longer in Afghanistan— Biden is right and I have a real problem with the conservative use of that word “weak.” Charging “weakness”—the GOP’s go-to foreign policy insult since World War II—suggests that it would have been “stronger” for President Ford and his successors to keep fighting the futile Vietnam War for—how long?—after the 1975 withdrawal and “stronger” for Biden to have the U.S. stay in Afghanistan for another 20 years or more.

…historians will puzzle over how the Biden Administration failed to grasp the gravity of the military and political decay inside the Kabul government, failed to cut red tape on visa applications, and failed to develop a contingency plan for avoiding a chaotic retreat.

Conservatives fundamentally view war as strong and peace as weak. But often the strong position is the one that recognizes reality: Both wars were unwinnable, if winning is defined as making those countries more like the U.S. Often, resisting or ending war takes much more political guts and inner strength than engaging in it.

As Carter told me, if he had bombed Iran, he would likely have been reelected in 1980. But the hostages and a lot of Iranians would have been killed in the process. So he chose a daring rescue mission, whose failure made him look inept, and then resumed diplomacy, which may have looked weak at the time, but eventually got the hostages home safely.

The conservative idea that choosing reality and diplomacy costs us “credibility” in the world has been disproven by events. For instance, documents from the Soviet archive show that—contrary to the assumptions of hawks—the failure of Washington to intervene on behalf of the Saigon government in 1975 and the Shah of Iran in 1979 were not factors in the Soviet decision to invade Afghanistan in 1980. (In fact, the documents show the Soviets invaded because they felt Kabul was tilting towards Washington).

The conservative idea that choosing reality and diplomacy costs us “credibility” in the world has been disproven by events.

The Soviets stayed there for nine years - which is a long time - but not 20 [like the U.S. in Afghanistan]. They, too, lost much in blood and treasure. But unlike us, they had nothing to show for it. The U.S. achieved its two main objectives—preventing Afghanistan from being a staging area for attacks on the American homeland and bringing the man behind the 9/11 attacks, Osama bin Laden, to justice, which happened in 2011. Once those two objectives were achieved, President Obama began winding down our commitment.

For Karl Rove and the other Bush people who diverted attention from that core mission with their foolhardy Iraq War to be saying anything now about withdrawal from Afghanistan reflects Trump-level shamelessness. Same for Mike Pompeo, who negotiated a May 1, 2021 date for withdrawal of U.S. forces. And all of them—starting with Bush himself—should stop blaming Biden for what will happen to Afghan women. When was the last time you heard any of them say anything about the way Saudi women are treated?

The U.S. achieved its two main objectives—preventing Afghanistan from being a staging area for attacks on the American homeland and bringing the man behind the 9/11 attacks, Osama bin Laden, to justice, which happened in 2011.

Of course Biden’s miscues gave these and other critics plenty of ammunition. The MAGA crowd can’t easily argue against a withdrawal set in motion by Trump so they are retreating into their usual racism and immigrant-bashing.

Meanwhile, old neocons engage in their own imprecise historical analogies, like Bret Stephens’ dubious claim that staying in Afghanistan is comparable to maintaining U.S. troops in South Korea—a place where, unlike the Middle East, no shots have been fired in anger in nearly 70 years.

Stephens and others also claim that the Taliban will once again harbor terrorists who attack the U.S. This is yet more faulty historical reasoning, based on the facile assumption that that trillions he and others urged us to spend in the “War on Terror” bought us no protection.

To defend himself—and salvage as much as he can of his policy, if it can be called that—Biden needs to take a leaf from Carter, who ignored critics and brought tens of thousands of Vietnamese “boat people” to the U.S., where they by and large became enormously productive citizens. (In recent days, many veterans have said they would happily help absorb Afghans).

As I explain in my 2010 book, The Promise: President Obama, Year One, Biden was right in 2009 and 2010 in initially opposing the troop surge in Afghanistan. He preferred “counter-terrorism” (drone strikes and commando raids) to “counter-insurgency” (ground troops and nation-building). But he was not secure in his judgments and told me he was glad Obama was president and not him.

And Biden was wrong in his apparently callous indifference to the fate of friendly civilians. As George Packer reported, in 2010 when Richard Holbrooke, President Obama’s special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, asked what a complete withdrawal would mean for Afghans who trusted us, Biden replied: “Fuck that, we don’t have to worry about that. We did it in Vietnam, Nixon and Kissinger got away with it.”

[In 2010] Richard Holbrooke…asked what a complete withdrawal would mean for Afghans who trusted us, Biden replied: “Fuck that, we don’t have to worry about that. We did it in Vietnam, Nixon and Kissinger got away with it.”

In the better-late-than-never department, Biden has apparently found his inner decency and accelerating evacuations. And by engaging diplomatically with the new government, Washington may even be able to incentivize the Taliban to keep their repeated promises not to throw women out of school.

None of this will satisfy the hawks now flying out of the rafters. The premise of their argument—based on a misuse of history— is that withdrawing from Afghanistan will make it hard for our allies to trust us. But it turned out that leaving Saigon and declining to intervene on behalf of the shah not only did nothing to inspire our enemies—it did nothing to demoralize our friends or weaken U.S. security guarantees and treaty obligations around the world.

…it turned out that leaving Saigon and declining to intervene on behalf of the Shah not only did nothing to inspire our enemies—it did nothing to demoralize our friends or weaken U.S. security guarantees and treaty obligations around the world.

Will this time be different? Will, say, China be emboldened to move against Taiwan because the U.S. isn’t willing to spend another 20 years in Afghanistan? Will long-time allies now turn to China and Russia? I doubt it. Yes, last week’s fiasco embarrassed—even humiliated—the Biden Administration around the world. It disappointed supporters who assumed its early signs of competence on Capitol Hill and its success in vaccinating millions would extend to foreign policy.

But if the U.S, government can finally execute its mission and evacuate tens of thousands of Afghans, that photograph of men running on the tarmac need not become iconic. Ford’s political fate in the 1976 election had nothing to do with the humiliating retreat from Saigon the year before. It wasn’t even a minor issue in his narrow loss to Carter. Biden’s fate in the midterms will also not likely be shaped by events in Kabul. The reports of major political and strategic fallout from the fall of Afghanistan are greatly exaggerated.

This smart analysis reveals how short-sighted neocon hypocrites cherry-pick history and exploit foreign kinetics for crass political gain. I appreciate Jon's panoramic considerations of these compelling events.

Great analysis Jon!!