Day 11: Hope Hicks’s Journey from Trump Acolyte to Reluctant Prosecution Witness

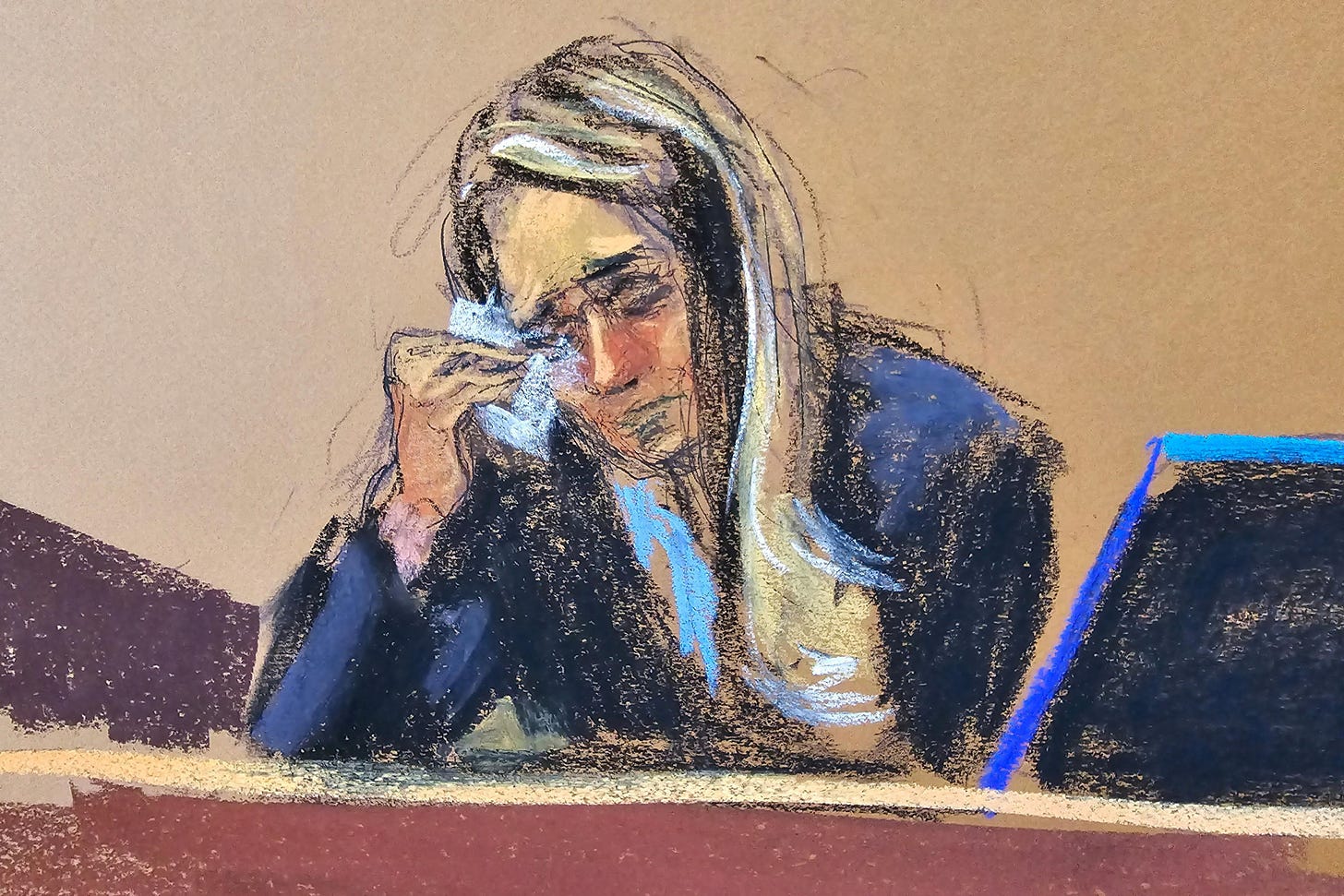

Her tears watermarked a devastating account of Trump’s lies.

If Donald Trump is convicted and loses the election, “The Cry” may become shorthand for why.

It’s reminiscent of how “The Scream” was viewed as ending Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign even though the truth was more complicated.

To stipulate: Trump’s fate in this trial depends on the jury’s assessment of the evidence, not on an emotional moment that no one other than Hope Hicks (likely in a book) can fully explain.

Trump could lose to Joe Biden for many reasons, though it seems to me that it would harm Trump to have to admit in a debate that as a convicted felon in the state of Florida, he cannot vote for himself for president.

The felon-nominee will bitch and moan about Democratic jurors in his hometown of nearly 75 years. But polls show that conviction is a bad look for a significant number of Republican voters, not to mention Democrats and — crucially — independents.

Whatever her explanation, Hicks’s tears watermarked the most devastating part of her testimony against her old boss. It’ll be easy for the jury, which sits just a few feet away from the witness stand, to remember that the weeping came not at some hard-to-remember moment but shortly after Hicks strongly suggested that President Trump was lying to her in 2018 when he said that Michael Cohen paid off Stormy Daniels “out of the kindness of his heart” and without his knowledge.

Trump’s denial of knowledge is contradicted by his social media posts and by his deposition in a civil case involving Stormy Daniels, in which he confirms reimbursing Cohen. We will likely hear about that admissible civil case within the next few days.

In the meantime, the prosecution ended its direct examination of Hicks and sent the jury home for the weekend with a bang: first-hand confirmation that Trump was motivated by concerns about the impending 2016 election.

Day 11 began with Judge Juan Merchan reminding the defense team before calling in the jury that the “order restricting extrajudicial statements” (i.e., gag order) only applied outside the courtroom.

Trump has been saying on the campaign trail that the judge was shutting him up. Now, Merchan was taking pains to set the record straight. He told Trump from the bench that he, as a defendant, has the right to testify about anyone, including, though he mentioned no names, Michael Cohen, Stormy Daniels, and other prosecution witnesses. I guess that means that if he’s dumb enough to attack jurors to their faces, he’s entitled to do that, too.

But I wondered: Might Trump take this as an inadvertent invitation to make speeches from the witness stand? We’ll see. I increasingly think he will testify if only to shake things up — drama-king style.

With the jury back, the defense began the day with continued cross-examination of Douglas Daus, who works in the DA Office's high-tech analysis unit.

Daus came across as a highly credible witness throughout. He’s an Iraq War veteran who, with Michael Cohen's consent, obtained and analyzed the metadata of Cohen’s two iPhones. Because he was the one assigned to validate what was on the phone, the prosecution got to play for the jury (not for the last time) the tape of Trump and Cohen talking about hush money (“So pay with cash,” Trump can be heard saying), an important piece of evidence.

On cross, Bove first made it seem as if Daus was suspect because he was doing standard work for a district attorney. Then he thoroughly bored the court (including Trump, who caught some shut-eye) with technical jargon (e.g., “artifact from CP1”) designed to make it seem as if Bove knew what he was talking about instead of just setting up an improbable conspiracy theory.

He did this by focusing, ala Johnnie Cochran, on the chain of custody of the phones and Cohen’s astonishing 39,745 contacts, 30 times more than even well-connected people possess. Daus explained that there was no evidence that the phones or the audio recordings were being manipulated in any way. But Bove got him to agree that the absence of a complete record of the chain of custody “presents risks.”

Bove left the extent of the risk to the imagination of conspiracy-minded jurors, though he used innuendo in his questions to bring the FBI and Cohen under vague suspicion.

I’m told by lawyers that reasonable doubt about the chain of custody is not enough to discredit that evidence, much less the prosecution’s case. But Bove did score by pointing to a nano-second gap in the audio of the key tape, the kind we all experience any time another call comes in. However, because Cohen did not put Trump on hold to take the other call, there is no record of it.

As the prosecution made clear on redirect, there is also no record of Cohen, the FBI, or anyone else “manipulating or tampering with audio recorded on the phone.”

The next witness was Georgia Longstreet, a paralegal with the DA’s office, whose job it was to monitor and log Trump’s social media accounts, including the video statement he made after the Access Hollywood tape, where he admitted to saying “foolish things” and (sort of) apologized before launching into an attack on the Clintons. This testimony offered the first but not last chance to present jurors with various videos and social media posts embarrassing to Trump, like “YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU!” last year on Truth Social.

Neither side has released a full witness list, so we were all surprised when Hope Hicks strode into the courtroom, clad in a smart black suit and looking more than a little like Ivanka Trump, who helped her get a big job at the Trump Organization when she was only four years out of college. By the next year, she was the communications director for a presidential campaign.

For what it’s worth, my take on her tears is that she retains her gratitude for everything Trump has done for her in the last decade. But when that gratitude and her close relationship with Trump came into conflict with her oath to tell “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth,” the oath won —and the pain followed.

“I’m really nervous,” she said at the beginning of her testimony, adjusting the microphone on the witness stand. But the nerves did not prevent her from being a compelling, appealing, and ultimately devastating prosecution witness.

Hicks described Trump as a boss who approved every Tweet and press release, testimony that corroborated David Pecker’s testimony depicting Trump as a “micromanager.” This will make it harder, though hardly impossible, for the defense to claim that Trump didn’t know that the checks to Michael Cohen were reimbursement cover for paying off Stormy Daniels.

Hicks recounted how David Fahrenthold of The Washington Post emailed her that the Post had learned of what would become known as the Access Hollywood story. He included a full transcript of Trump caught talking to Billy Bush about being able to “grab ‘em by the pussy” among other disgusting comments.

While the tapes were deemed by Merchan as too prejudicial to admit into evidence, the transcript —after much debate in front of the judge — is an exhibit. It was not read from today but flashed briefly on the monitors. I didn’t see “pussy,” but I was able to quickly read: “And I did try to fuck her. She was married.”

When Hicks brought the transcript to Trump, “He said that that didn’t sound like something he would say.” In other words, Trump lied to her, which became clear later in the day when the tape itself was obtained. Jurors might suspect that Trump is a liar based on their familiarity with him over the years. But this was the first time they heard evidence of it in court.

And they learned that his lying was contagious. After Trump lied to her, she instructed her communications staffers to “deny, deny, deny.” In other words, to “lie, lie, lie.”

After the tape aired, she testified that Paul Ryan, John McCain, Mitt Romney, and many others jumped ship, and many Trump staffers thought the campaign was over. “The tape was damaging. This was a crisis,” Hicks said, noting that the story was so big it pushed a Category Four hurricane out of the headlines.

She confirmed exhibits showing that Trump was also very concerned in the last weeks of the 2016 election about The Wall Street Journal story detailing catch-and-kill with the Karen McDougal story, and the jury saw a video of Trump on the campaign trail worrying aloud that the multiple accusations of sexual misconduct launched after the Access Hollywood tape might cause him to lose.

Hicks apparently knew nothing about Cohen’s payoff to Stormy Daniels at the time, but when the story broke in the Journal in early 2018, she and Trump had a fateful chat about it in the White House.

In a rare piece of good news for the defense, she testified that Trump was worried about his wife: “He wanted me to make sure the newspapers weren’t delivered to her residence that morning. He was worried about how this would be viewed at home…I don’t think he wanted anyone in his family to be hurt or embarrassed. He wanted them to be proud of him.”

“President Trump really values Mrs Trump’s opinion. He really respects what she has to say. And I think he was concerned about what her perception of this would be.”

But this testimony was undercut by what the jury heard next:

Hicks testified that when the payoff to Stormy Daniels became public in 2018, she and President Trump discussed the matter in the White House, and Trump told her that Michael Cohen had paid the porn star “out of the kindness of his heart and never told anyone about it.”

Prosecutor Matthew Colangelo then asked a critical question:

Was this “consistent” with what she knew about Cohen?

“I’d say that would be out of character for Michael Cohen,” Hicks told the jury. “I didn’t know him to be an especially charitable person or selfless person,” she said. To the contrary, “Cohen was “The kind of person who seeks credit.”

A clueless Trump smiled when she later explained that Cohen’s moniker, “Trump’s fixer,” had come from him. He was a fixer “only because he broke it so that he could fix it.”

Of course, this just made her testimony doubting Trump’s claim that Cohen acted out of the “goodness of his heart” line even more powerful.

The next part of the fallout from the news of Stormy Daniels going public I’m quoting in full from the transcript:

Q. Did he say anything about the timing of the news reporting regarding—

Oh, he—yes.

He wanted to know how it was playing and just my thoughts and opinion about this story versus having the story—a different kind of story before the campaign [election] had Michael not made that payment.

And I think Mr. Trump’s opinion was it was better to be dealing with it now, and that it would have been bad to have that story come out before the election.

Q. Thank you.

MR COLANGELO: No further questions.

The defense will presumably argue that any rational candidate would not want the story of a fling with a porn star to come out before an election.

But the prosecution was able to end direct examination with a bang because it has built a narrative for the jury that consists of: Trump’s frenzied reaction to the Access Hollywood tape; Trump’s admissible campaign speeches where he openly worries that the accusations of misconduct from several women in October will cost him 5 to 10 percent of the women’s vote; Cohen’s sense of urgency in creating a dummy corporation and bank account and wiring the $130,000 to Keith Davidson all within a 24-hour period; and the testimony of Pecker, Davidson and, soon, Cohen.

With Hicks’ testimony, the motive and criminal intent necessary for conviction have been reaffirmed by someone who worked closely with Trump, still admires him, and heard that motive expressed directly to her, not as hearsay testimony.

Trump may have wanted to spare Melania, but his first priority was to interfere in the election.

No wonder the prosecutor said, “No further questions.”

It was now time for Bove’s gentle cross-examination. For a minute or two, he asked a subdued Hicks about her background.

He mentioned her first job with the Trump Organization and asked, “Real estate host and entertainment, that was your portfolio there?”

“Yes, she said.

Then, as the transcript reflects, she began softly crying.

This caused some brief confusion in the courtroom over what we were hearing.

After murmuring “Sorry” three times, Hicks asked, “Could I just have a minute?”

Bove requested a break, and the judge asked, “Do you need a break?” Between sobs that I could now hear from the second to last row of the courtroom, she said, “Yes, please.”

After the break, Hicks mostly regained her composure, and Bove’s easy cross continued in unmemorable fashion before petering out.

Hicks, who had not seen Trump in 18 months, exited the courtroom by walking just three feet to the right of her old boss. She looked straight ahead; he looked away.

Trump should have been thinking this but has never shown any familiarity with Shakespeare:

“Et tu, Hope Brute?”

I think it's finally hitting her how absolutely wrong and out of line they all were acting while Trump was in office!! And she was part of it so that's why I think she's crying. Remember she actually resigned way before he lost the election.

That's a sharp observation - that a presidential campaign can be suddenly extinguished in a burst of human emotion. Besides Howard Dean's scream and Hope Hicks' sobs, there was Sen. Ed Muskie's angry denunciation of publisher Wm. Loeb for printing a false story depicting the candidate as a racist during the 1972 NH presidential primary. Frontrunner Muskie appeared on the steps of The Manchester (N.H.) Union Leader on a snowy day: some reporters thought he cried, but Muskie claims it was just melting snow on his tired, angry face. In the end, as Muskie later admitted, his emotional outburst eventually sank his campaign.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/02/09/new-hampshire-ed-muskie-tears-primary/