Colin Powell was a formidable pioneer—the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the first Black national security adviser and the first Black secretary of state. But he was also a tragic figure, forced to peddle fake intelligence that got a lot of people killed in Iraq. And when he turned his attention to the noble task of helping at-risk kids at home, his significant contributions were almost completely ignored.

In early 2001, two weeks before he was sworn-in as George W. Bush’s secretary of state, Powell invited me to a small conference at Epcot Center in Orlando. Just before dinner, we chatted for a while off-the-record about what he could expect when he went back into government.

I brought up the neocons—hawkish foreign policy intellectuals like Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz, who were slated to have influential jobs at the Pentagon. Wouldn’t they undermine him?

Powell scoffed. He was famous for keeping it light, but could be cutting and dismissive. I can’t remember exactly what he said about the neocons, but the gist was that they wouldn’t get to first base in the new Bush Administration. In this he was fatally mistaken.

Even before 9/11, Powell— a non-ideological problem-solver—was being undermined by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who held a black belt in bureaucratic infighting going back to the Nixon Administration 30 years earlier. Powell had worked closely with Dick Cheney during the 1991 Gulf War but they were not friends—had not socialized even once—and before long the vice president was rolling over the secretary of state. It seemed as if every time Powell left the country on a diplomatic mission, his colleagues figured out a new way to undermine him. Foggy Bottom was soon lost in the fog of war—not with America’s enemies but with other parts of the government.

Powell wasn’t thrilled to be asked by Bush to lend his great prestige to making the case for war. The night before his infamous U.N. speech, he spent hours deleting or softening charges that seemed to lack sufficient evidence. But he left in whole chunks of pure horse shit.

Anyone who wants to understand how Powell got jammed by the CIA should read Curveball by Bob Drogin. It’s a compelling and truly depressing story, especially for the 100,000 dead Iraqis and several thousand killed or maimed Americans. “Curveball” was the code name for the Iraqi defector who received a nice apartment and a new life in Germany in exchange for feeding German intelligence a bunch of lies about WMD mobile labs and poison gas. The CIA had such a horrendous case of confirmation bias that no one from the Agency even bothered to interview Curveball to see whether he had conned German intelligence. The CIA officials who tried got muscled aside in favor of the ass-kissers. (Remember CIA director George Tennet telling Bush that evidence of Iraqi WMD was a “slam dunk?”)

By 2005, Powell’s former chief of staff, Lawrence Wilkerson, was calling the whole thing a “hoax” and blaming the same neocons Powell told me wouldn’t be a problem. Powell wouldn’t go that far but he did tell Barbara Walters that the UN appearance would be “a lasting blot on my record.”

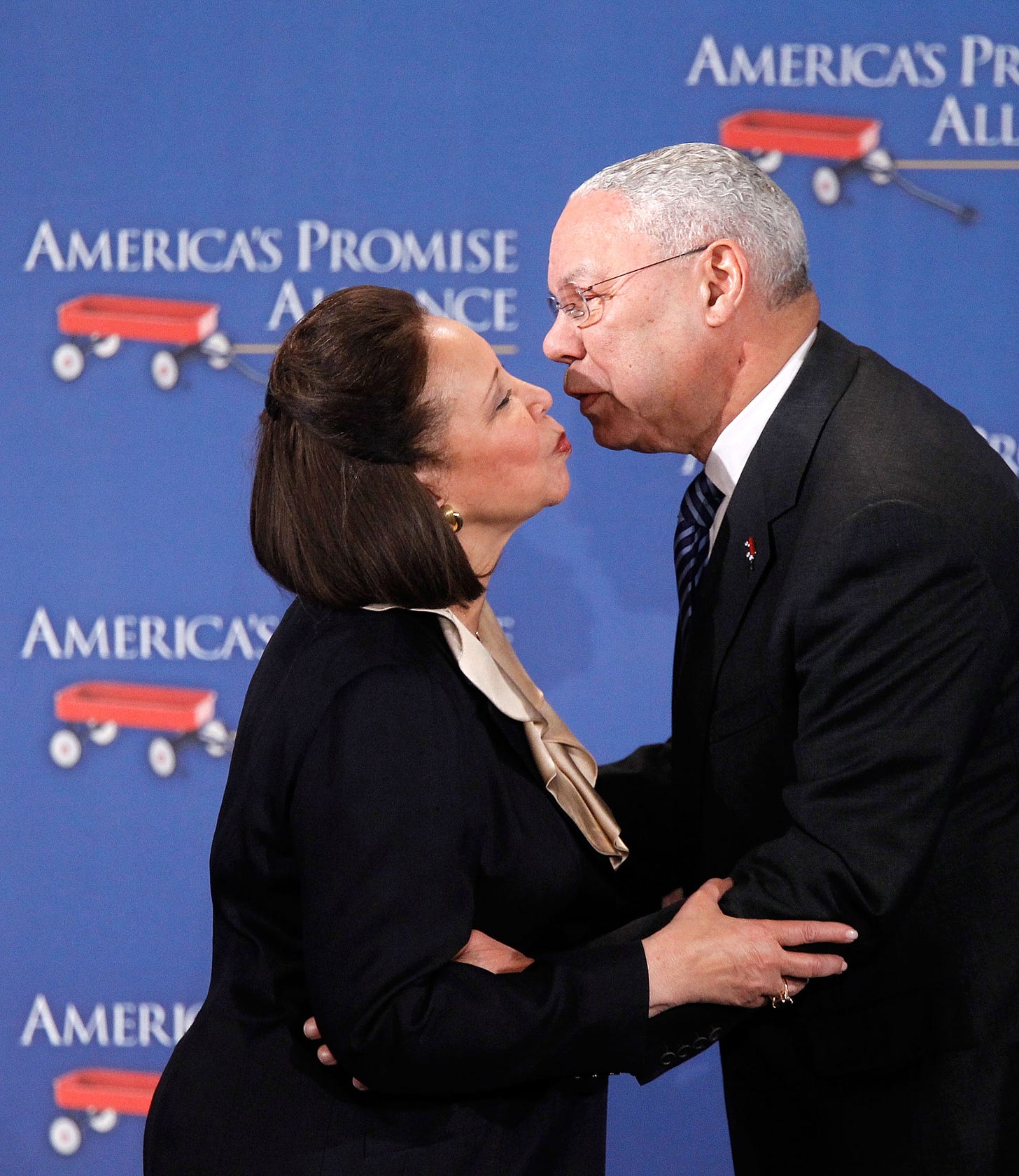

This was the low point of Powell’s mostly-stellar career and the long obituaries took note of it. But they made only passing reference to another part of his life that for the last two decades has been extremely important to him. America’s Promise, the organization Powell founded in 2000 and which has been chaired in recent years by his wife, Alma Powell, is treated by the press as a footnote at best. No one points out that, despite plenty of ups and downs, the Powells’ efforts on behalf of at-risk kids have helped bear real fruit, with teenage pregnancy and drop-out rates both falling sharply.

America’s Promise is an outgrowth of the Presidents’ Summit for America’s Future—a big, splashy event hosted by President Clinton in Philadelphia in 1997. The summit was attended by four of the five living presidents (Reagan was ill and Nancy attended in his place), 20 governors and thousands of people involved in helping at-risk kids in the United States.

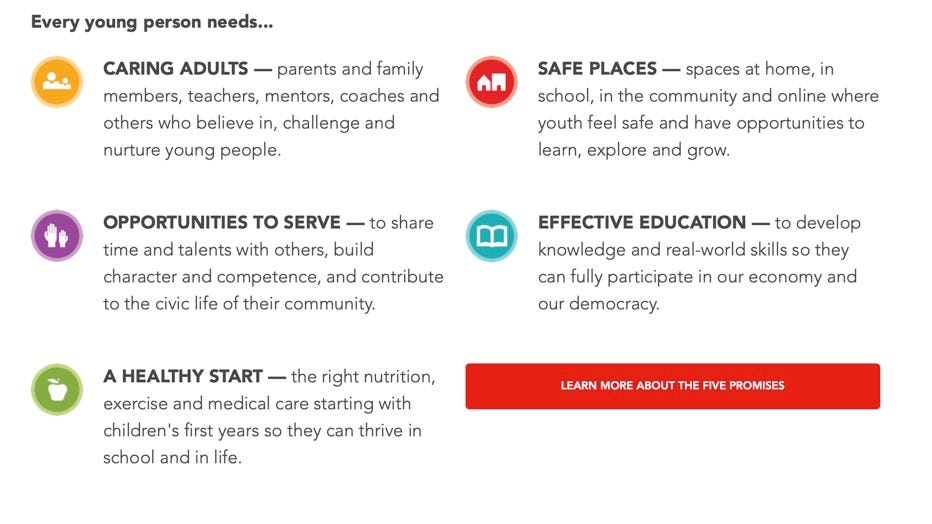

Powell and his compatriots organized the effort around “Five Promises” to children—promises that Powell took very seriously:

Caring adults to guide them (more tutoring and mentoring programs); safe places to learn and grow (more after-school programs); a healthy start (better nutrition and exercise); education for work and life (better schools, with better connections to non-profits and employers); and service learning (which means engaging kids in community service that often helps them as much as those they serve).

The event captured my imagination because it launched an idea that many conferences—including the Clinton Global Initiative—have used to great effect in the years since. Instead of just hosting the normal well-intentioned schmooze-fest, Powell and company only invited politicians, non-profits and corporations that made specific “commitments” in one of the five areas.

That gave me an idea. I decided to play attendees off against each other. For example, when Wal-Mart committed tens of thousands of employee hours to tutoring and mentoring, I used a Newsweek graphic to write “Paging K-Mart in aisle 6.” The next day, a press release from K-Mart would arrive with its own ambitious commitment. The pledges multiplied, a combination of PR and a genuine effort to help.

When this little gambit came to Powell’s attention, he called me up and said to come see him. After the summit, Powell decided that—having served in senior positions in the government for close to 30 years—he would establish a non-profit to do the unsexy work of building alliances between the hundreds of agencies and non-profits devoted to helping kids.

In 2000, I traveled around the country with Powell in a small plane as he promoted America’s Promise, whose symbol was a little red wagon. His great charm and rock star status helped him get all of the stakeholders on the same page, at least for a while. In writing follow-up stories about America’s Promise, I was disappointed that Powell’s chumminess with CEOs and heads of big non-profits prevented him from wielding the stick when more than a few fell short on their commitments.

But the fact remains that the high school drop-out rate fell from 30 percent to 18 percent in the last 20 years. While it’s impossible to draw a straight line from America’s Promise to any particular social improvement, these new, better-organized alliances—fostered by Colin and Alma Powell—have made a difference.

With his death, Powell’s mistakes are being properly put in the context of a great American life. Over time they will recede further, as appreciation deepens for this decent, honorable and inspiring public servant.

Paul Michaels For me, the general was a real-life role model without ever meeting him.

Love your “black-belt in infighting.”

I’m moved by his life changing work for children and am sorry I didn’t know about it till now. Thank you