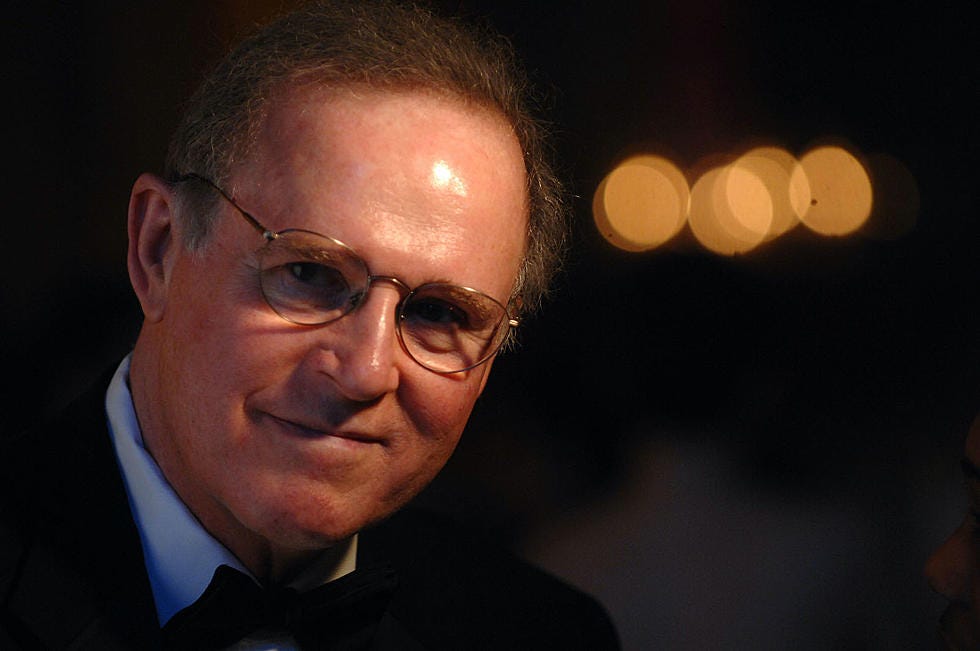

Charles Grodin (1935-2021)

The cranky mensch I knew cared more about the wrongly imprisoned than Hollywood

In 1990, Charles Grodin made one of his many curmudgeonly appearances on Johnny Carson. “What do you care about in life? Do you care about anything?” he asked Carson with what seemed like faux contempt for the host’s self-absorption. “Do you care about the human condition?”

This was part of Chuck’s peculiar and super-funny act but it was also a genuine expression of who he was and what he valued. When I met him five years later and - despite a 23-year age difference - we became friends, I was struck by the depth and passion of his liberal commitment to improving the human condition, and his little-known success in doing so, as I’ll explain. He was a cranky mensch—an eccentric altruist.

Chuck and I first got to know each other after he left show business. He told me he was sick of yelling “Honey, the dog!” in Beethoven movies. While proud of The Heartbreak Kid (one of my all-time favorite comedies) and always happy to describe how he and his co-star, Robert De Niro, improvised the box car scene in Midnight Run, he was sick of the industry.

In 1995, Roger Ailes—who appreciated talent of any political persuasion— gave him a talk show on CNBC, though Ailes soon left to help launch Fox News. The big story Chuck’s first year was the O.J. Simpson trial, and he had me and Tavis Smiley on many times to talk about O.J. and other topics. My favorite appearance was when he gave me a chance to take down Noam Chomsky. He later told me I was his most frequent guest, which may help explain why he only had a three-year run.

Chuck’s halting monologue—where he peered to the right and said nothing for several seconds before blurting out an interesting non-sequitur—was parodied by Dana Carvey. Early on, Chuck’s mother died. Every night, he ended the show by staring off-camera and saying, “Good night, mom.”

My wife Emily and I often joined Chuck and his wonderful wife, Elissa, for dinner at various restaurants in Connecticut - no later than 5 PM. One time, we traveled 90 minutes from our house in New Jersey to join them for cocktails with former Governor Mario Cuomo and his wife, Matilda, Phil Donahue and Marlo Thomas, Regis Philbin, and Gene Wilder. When the sun went down, Chuck—to Elissa’s chagrin— shooed all of us out: “Time to go! Time to go! Time to go!” We had been there no more than half an hour.

“Time to go! Time to go! Time to go!”

At some point Chuck bought an apartment in New York but he decided he couldn’t ever spend the night there—and didn’t. It remained empty for years. If Chuck had to stay overnight somewhere for something, the list of food, sheets and other requirements was long, not because he was an entitled celebrity but because he was….Chuck.

This was all easy to overlook because of Chuck’s boundless compassion, as his family can attest. His daughter Marion once sent me a draft chapter of a memoir that she was planning and at first I thought, “Oh, here’s the dark side.” But it was about their wonderful relationship after he and her mother (Chuck’s first wife) divorced. It ended with a story from the 1970s in which Chuck tells his young daughter he’s renting a house for the summer in Los Angeles with Simon and Garfunkel, Carrie Fisher, Rob Reiner, and Penny Marshall— and he has arranged for a room for her there.

When I underwent a bone marrow transplant for lymphoma in 2004, Chuck went far beyond the ministrations of much closer friends--sending me funny tapes and books; calling me regularly to get a laugh out of me when no one else could; and making sure I met others in the same awful club so that we could commiserate in ways that he knew he couldn't. I'll never forget that.

After his talk show ended, Chuck became a commentator for “60 Minutes II” and an author. The book that may have summed him up best was a collection of essays by 82 friends (including me) on mistakes we have made along the way and what we learned from them. He convinced everyone from Walter Cronkite and Shirley MacLaine to Peter Falk and Ben Stiller to contribute.

Chuck’s most defining characteristic was his idealism, which was fueled by moral outrage. For more than two decades, he worked tirelessly to free prisoners serving long sentences for non-violent offenses. He took cameras to the Bedford Hills, N.Y. Correctional Facility and interviewed four women, one of whom, Elaine Bartlett, explained how she had four children in Harlem and no money and was asked to deliver a small packet of cocaine to Albany for $2,500. When she did so, she was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 20 years to life.

Chuck went to Albany, where he got a better reception from Republican lawmakers than from Democratic Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who himself later went to jail. The four women were granted clemency and in 2004— in partial reaction to the Bartlett case—New York repealed the notorious Rockefeller Drug Laws, which allowed more than 1,000 mostly young mothers to be reunited with their families. Chuck kept up the pressure and in 2010 won another clemency, the only one granted that year in New York.

Whenever I’d go out in public with Chuck, fans would approach to tell him they loved seeing him with Cybil Shepard in The Heartbreak Kid or Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby or on some late-night show. He would be happier if people remembered him for getting poor women out of prison.

I loved your tribute so much that I subscribed to your newsletter. There's so much content and so many platforms out there -- but your writing was so eloquent that it cut through the clutter.

I had the opportunity to meet Charles Grodin twice at book signings.At one signing he graciously inscribed my old copy of ‘It Would Be So Nice If You Weren’t Here’for my daughter and ‘How I Got to Be Whoever It is I Am’ to me. As he was signing the books we spoke about his friend, playwright Herb Gardner. He shared some memories. I mentioned that at Gardner’s memorial Tom Selleck read the speech Gardner wrote for Selleck to read at the curtain call of the first post-9/11 Broadway performance of A Thousand Clowns. Grodin told me that he was managing the memorial backstage and never heard Selleck. Fortunately, I had a copy of the speech with me.(I’d written Mrs. Gardner requesting a copy.) I was able to give it him. He struck me as a generous, thoughtful and decent man.