Book Bans Are Big Again in America

On both the left and the right, free expression is under attack, says the CEO of PEN USA.

As you may have noticed, I’m a bit obsessed right now with challenges to free speech and local autonomy in education, and the way it now cuts both left and right. After the infamous incident at Hamline College involving an art history professor fired for showing a classic painting that offended a Muslim student (which I discussed with Amna Khalid), we now have video of a condescending Stanford Law School dean of DEI who seemed to endorse the heckling of a federal judge by students. To get a broader perspective, I ruminate here with my friend Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America and author of Dare to Speak: Defending Free Speech for All. Suzanne is a leading human rights activist and under her leadership PEN has fought book bans all over the country, while continuing its longtime mission of defending freedom of expression abroad. Even when we disagree, Suzanne’s good sense shines through. At 53, she is much too young to be an “old goat” but as with the even-younger Amna Khalid, I thought the importance of her message took precedence over her youth. Read on for insights into book bans, campus free speech, and how we teach American history in schools.

JONATHAN ALTER:

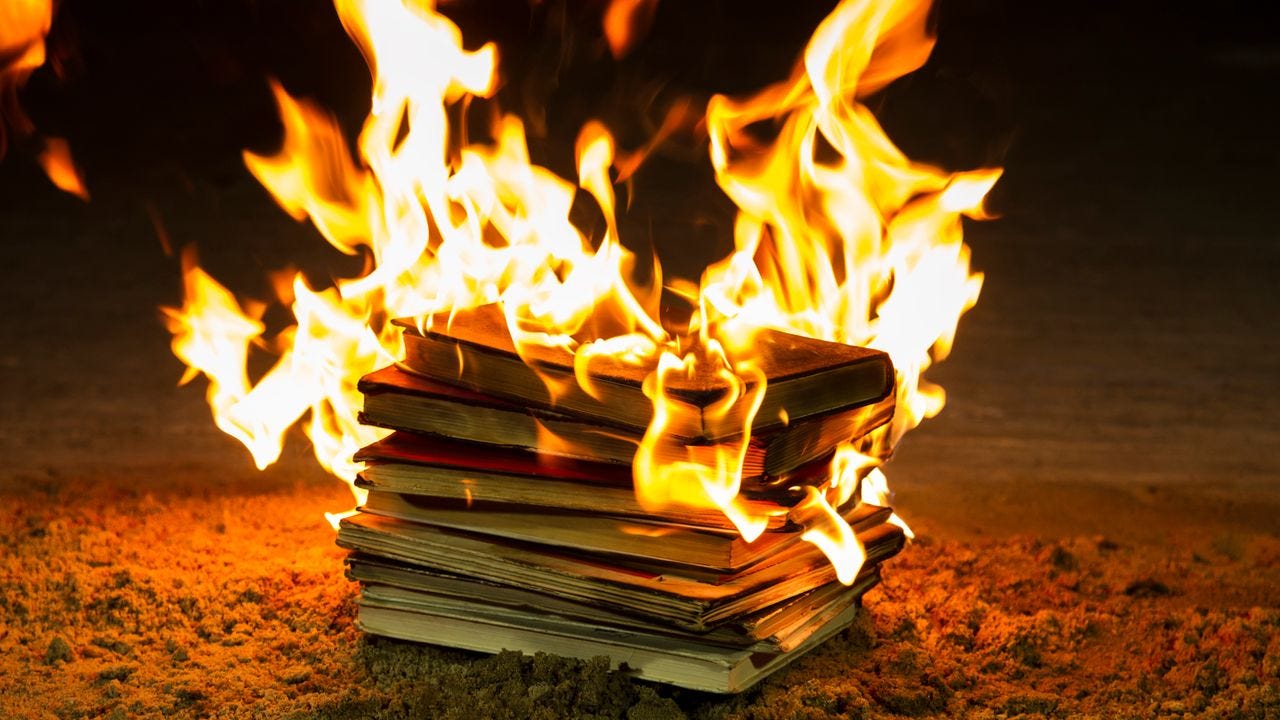

I’d like to get a sense from you of the scope of the problem and what we can do about it. When we hear “book ban,” we think of Nazis burning books, or maybe stories from the 1950s. But book banning is back, right?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

When I first got to PEN [2013], I was almost amused that the organization still worked on book bans. Over the course of a year, we’d find out about one or two book that were removed from the shelves. Usually we’d write to the principal or the librarian and ask them to put it back, and that was the end of it. It seemed very quaint. I never imagined that it would make a comeback as a tactic of choice, but it has. It’s part of this fear-mongering about what's happening in our educational system. And it's a reaction to efforts to open up the discourse to new voices and new perspectives, and to elevate histories and narratives that were less focused on in the past.

“Usually we’d write to the principal or the librarian and ask them to put it back, and that was the end of it. It seemed very quaint. I never imagined that it would make a comeback as a tactic of choice, but it has.”

That has triggered a ferocious backlash. There is a feeling in certain states and communities that schools are under left-wing ideological domination, that students are being indoctrinated, that they're being turned against the United States or being steered toward LGBTQ lifestyles and identities, that they're learning to hate themselves because of their race. The only way to meet this threat, in the eyes of those behind this movement, is through the heavy hand of the state and legislation — by imposing book bans to limit what can be taught in college and high school classrooms, by increasingly empowering citizens almost as vigilantes to report on violations of these bans and prohibitions. So it's a real resort to authoritarianism. I can sympathize with the idea that sometimes things go too far on the left, whether it's curricula or training sessions that veer into ideological indoctrination. I might contest their utility. But to respond to that through legislation and the policing of speech, to me, is a far worse violation of freedom of expression.

JON:

The stories are chilling. A Florida publishing company responded to Ron DeSantis’ “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” by taking out any reference to the color of Rosa Parks’ skin as the reason she was sent to the back of the bus. But how big a problem are we talking about? How many states and how many school districts?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

We're working now on a new, updated book ban report for the current school year. When we documented bans last year, there were more than 2,500 in communities across the country. When it comes to educational gag orders, many more have been introduced than have been actually adopted. At our last count, there were 19 laws on the books in 15 states and nearly 200 bills introduced over the last two years.

JON:

Fifteen states! That means this is not just a problem in the Deep South. This is going on all over the country, and it's extending to all kinds of books that seem pretty anodyne.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

This is not the old-fashioned scenario of a parent opening up a backpack and finding a book that seems too mature for the kid’s reading level, where there are sexually explicit pictures, perhaps, and objecting to the school. That's not what's happening. This is wholesale. There are lists of banned books that are being put together and circulated. In some instances, book lists that have been assembled for purposes of advancing more diverse literature — books that depict black heroes or LGBTQ families, or that foster inclusivity in some form. One such book depicts babies in all shapes, sizes, and colors. These books are being assembled for purposes of suggesting to teachers and librarians: “Hey, here are some volumes that can help reflect a wider range of identities in your school library.” Then they're getting into the hands of those who now call for wholesale bans of everything on that list, even if they [admit that they] haven't even read the book. It’s a galvanizing issue. If you can find something objectionable that people will rally around, they’ll derive a sense of empowerment from being part of a movement to exclude something from the curriculum, from the classroom, from the library bookshelf. Overwhelmingly, in the book bans we've documented, there's no written record of the objection or the adjudication.

“If you can find something objectionable that people will rally around, they’ll derive a sense of empowerment from being part of a movement to exclude something from the curriculum, from the classroom, from the library bookshelf. “

JON: What do you attribute it to?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

There was a lot of frustration among parents during the pandemic about learning loss and schools being shuttered. That drove a wedge of distrust between parents and school administrators and teachers. There’s almost a vengeful impulse, when schools reopened, to get back at them. I’m not proud of [the way] our school systems dealt with the pandemic and the relative lack of priority placed on giving kids normalcy and a proper in-person educational experience. But that understandable frustration has now curdled into something really noxious, combined with a fanning of anxiety about social change, whether it's the greater visibility of transgender individuals or the reckoning over racial issues during the summer of 2020. All of that has stoked this insecurity, a sense that something is being taken away, that things are changing outside of people's control. What you have in response is this virulent snatching back, a heavy-handed, intrusive effort to reclaim something that people have been told they're about to lose or have lost.

JON:

How much of this is going on in state legislatures and how much of it is going on at the school board level?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

They are mutually reinforcing. When a book gets put on a list in a piece of proposed legislation, even if it has not passed in the statehouse, school boards start to look at it and take action within their power. When a book ban fans up at the local level, state legislators begin contemplating: “Is this an issue where I might be able to make hay and derive political gain from proposing a legislative measure?” There's a real interplay in tactics, but what's held in common is this invocation of the power of the state, whether it's in the form of a school board or a legislature, to dictate what can be taught and learned and accessed in schools. For people who grew up appreciating very powerful protections for freedom of expression, this just seems completely at odds with the notion, in the study of the First Amendment, that viewpoint-based restrictions are the most problematic from a constitutional perspective.

“But that understandable frustration has now curdled into something really noxious, combined with a fanning of anxiety about social change, whether it's the greater visibility of transgender individuals or the reckoning over racial issues during the summer of 2020. All of that has stoked this insecurity, a sense that something is being taken away, that things are changing outside of people's control. What you have in response is this virulent snatching back, a heavy-handed, intrusive effort to reclaim something that people have been told they're about to lose or have lost.”

JON:

These are the same people who have been raising the alarm about restrictions on free speech, on campus and on the internet. And now they want to restrict free speech. It’s bald-faced hypocrisy, isn't it?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

They're going to destroy free speech in the name of trying to save it. In their minds, this is about countering enforced orthodoxies and ideological rigidity, but the tactic of choice is an even more orthodox and rigid set of methods — methods that invoke the power of the state. There's no sense of irony here, no recognition that once you [allocate] this power to a state legislature or a school board to ban the books you don't like, the next crowd that comes in can do the very same to books that you might value. As recently as the last Republican National Convention, the Republican Party was claiming the mantle of being the party of free speech and the First Amendment. To see this drastic and rapid turnabout is really startling.

JON:

But there are abuses on the left too. Hasn't Huckleberry Finn been banned all over the country?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

No, it hasn't. There are some book bans on the left, [including a few involving Huckleberry Finn]. One case we talked about is Burbank, California, where they have banned essentially all books that reference the N-word. So that's also James Baldwin and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, and all sorts of other things. But that's not widespread. Now, are there school systems quietly turning away from these books? That's quite possible. But it has nothing of the formality and the widespread nature that we see on the right. There are no legislative bans on books emanating from the left.

JON:

There are no legislative bans, but hasn't the left been leading with their chin by doing really dopey things? Take the University of Illinois Law School case, where [Professor Jason Kilborn] didn't use the N-word. He just referred to the N-word on an exam in a case where it was very relevant. And they've sent him to, like, a Maoist reeducation camp. He had to write a long and craven apology and promise that he had learned his lesson, when actually, given the case that he was presenting at law school, there was literally nothing to apologize for. First of all, do the excesses of left-wing cancel culture alarm you at all, even though they are not legislative? Second, why can't they be encouraged by others on the left to just knock it off? Why do they keep giving ammunition to Fox News?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

We first got into the whole area of free speech and education because of our concern about some stories coming from the left. We did a whole series of reports on the climate for free speech on college campuses. We put out a lot of thinking and guidelines, whole books defending free speech and how we can live together in our diverse, digitized and divided society without curbing free speech. I hear from a lot of students that you sit in the classroom and there’s a pall that hangs over it. If someone says something that departs from the script, everybody looks around uncomfortably. No one will respond, and there's a very uneasy feeling. Free speech has lost its moorings on the right and the left. That's what I worry about. The rightful impulse to be conscientious in how we talk about each other, how we describe things and the language we use can readily veer into powerful constraints on free speech.

“When we talk to young people we often hear some version of the idea that if protecting someone or fostering a sense of belonging necessitates a curtailment of other people's speech rights, this may be justified for the greater goals of equity and inclusion. That is the widespread mindset.”

When we talk to young people we often hear some version of the idea that if protecting someone or fostering a sense of belonging necessitates a curtailment of other people's speech rights, this may be justified for the greater goals of equity and inclusion. That is the widespread mindset. Part of the problem derives from a lack of grounding in free speech principles. People actually have never been taught about free speech or why we protect it or what can be so problematic about empowering those in positions of power to muzzle or silence it. If you don’t understand that it can be hard to understand why someone who's part of a marginalized group should have to endure offense, and why shutting down that problematic speech, and setting that precedent, may well be worse than having to endure it. We’re now doing a lot of outreach giving people basic grounding in free speech principles. One of the major points is that these principles are what made social movements possible, whether it's racial justice, gender justice, immigrants’ rights, climate justice. If you don't have the First Amendment and free speech protections, you can't bring these fights against people in positions of authority; they can just shut you down. And so we've developed a lot of detailed thinking about how it is that the drive for more equal and inclusive campus and society can and must be reconciled with uncompromising protections for free speech.

JON:

I've been quoting him so often that my wife is starting to roll her eyes when I say it — Michael Roth, the president of Wesleyan, said, very simply, “Nowhere in the Bill of Rights is there a right not to be offended.” Umbrage is not protected in our Constitution.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

I would put it differently. I don't think it's necessarily helpful to say umbrage has no standing and that your outrage or your feelings of offense hold no weight. They hold moral weight. They can be very real. True, they can be exaggerated and imagined and projected onto other people, but they also can be genuine. To dismiss them out of hand causes people to think of free speech as a conservative cause, or a smokescreen for hatred, or something that only benefits white privileged people. I think the better approach is to acknowledge those feelings, to recognize they may be legitimate feelings. Maybe you've endured slurs and stereotyping your whole life and someone says something in the classroom that others regard as just a mistake. It could land very hard for you and stoke up potent feelings. I don't think the answer is to just dismiss it. I think the answer is to engage it, but also to insist that the right response is not to ban or punish speech. You can support somebody who is offended, you can stand with them. You can, in some instances, even condemn the speech if it's bigoted or racist.

JON:

Maybe the students who are upset should be encouraged to go demonstrate and have rallies, but not try to prevent the expression of ideas, even if they offend them. They're working under the assumption that DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] should trump freedom of speech.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

How we talk about this is really important. It's so easy to caricature, and some of the incidents really are outrageous. But, to me, if we want to bring about some common ground on this, the better approach is to acknowledge that, very often, there's some legitimate kernel of why someone is objecting. The answer shouldn't be rewriting classic literature; the answer shouldn't be firing a professor or shutting down a newspaper. We need to be able to talk about these things, to acknowledge the variety of views, the diversity of perspectives, the equities that are at stake. To me, that’s a much more productive way to engage these really difficult questions.

“The answer shouldn't be rewriting classic literature; the answer shouldn't be firing a professor or shutting down a newspaper. We need to be able to talk about these things, to acknowledge the variety of views, the diversity of perspectives, the equities that are at stake.”

JON:

I take your point. You can make the situation worse if you respond without showing some sympathy for the people who are protesting. But it's a very fine line between that and giving them the moral high ground. In case after case, college administrators have given the activists that moral high ground and the conversations that they have with them begin with that as the premise: that they, rather than academic freedom and freedom of speech, have the more worthy values. You never see, say, the case of the Nazi march in Skokie, Illinois. I haven't seen an explanation of why the ACLU was right to defend the Nazis marching through a neighborhood of Holocaust survivors introduced into the debate. Certainly they had more reason to be offended than somebody who was offended not by the N-word itself, but the term “N-word.” Clearly, that person who is studying to be a lawyer at the University of Illinois would benefit from hearing about the Skokie case, but I feel like administrators are just in a pandering crouch.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

It’s true, the answer is not to run scared. So much of the rhetoric is hyperbolic: people are afraid to be accused of being transphobic or racist or sexist. Those labels, in our digital age, once they attach, can be very hard to shake; that terrifies people. There is this impulse to just quell the controversy by essentially going left. It's extremely important for those in positions of leadership to speak up on behalf of controversial speech, to make space for a wide range of views, not to take claims of harm as absolutes or justifications for shutting down all areas of conversation and inquiry. Some courage is needed.

JON:

I want to bring up the recent case of a Sarah Lawrence professor, Samuel Abrams, who wrote an op-ed in The New York Times on something trans-related and whose office was subsequently vandalized. The president of Sarah Lawrence waited for three weeks before denouncing vandalism and standing up for the professor and saying that he would not be fired for writing an article in The New York Times. And when I read that, I was like, why is this buried and why is the college president not called out by PEN?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

Maybe you didn't think the statement was strong enough, but we certainly spoke out about it.

JON:

Let me ask it this way. Tell me the difference between what the president of Sarah Lawrence has done and what book banners on the right do, beyond the fact that one has state power, and the other does not. I'm not minimizing the distinction, but as a moral matter, as a free expression matter. Tell me what the difference is between Ron DeSantis and the president of Sarah Lawrence College. Don't we, going into this next phase, need to find other ways to push back against these cases from the left and not just say: “Oh, yeah, they're annoying, but they're extremely minor compared to the right-wing abuses”?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

We've been working on campus free speech for years. We've done all of these reports — at this point, hundreds of statements about these kinds of incidents on campus. We've worked with a lot of campuses, we've traveled to a lot of campuses, done a great number of workshops about just this with students, faculty, administrators and leaders. What's challenging for organizations like us is: how do you break through?

JON:

Maybe PEN is at the vanguard because you have been working on it for several years. The only way that we can resist authoritarian attacks of the right wing, which are terribly alarming and terribly harmful, is if the academy and the rest of progressive America cleans up its own act. And the only way for that to happen is for not just PEN, but all kinds of different organizations to say to the weak-kneed administrators who are not standing up for free speech and academic freedom: “You're going to pay the price. We're going to call you out on it.” Then, maybe, we can be more united in pushing back against these horrible right-wing abuses.

One last question, on education gag orders. Typically these are bills that say you may not teach critical race theory in the schools in the state of Louisiana.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

That's the essence of it; there are a lot of variations.

JON:

What is the scale of that problem right now?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

We've done two reports. We have a new report that's going to come out about new variations on this type of legislation. In 2022, there were 36 states that introduced 137 gag order bills, seven of which passed. They're definitely being introduced at a far faster pace than in the past. The total number of gag order bills that are in place is nineteen in fifteen states. Twelve were passed in 2021 and seven in 2022. I don't think there have been any new ones yet this year.

JON:

In a lot of cases, they're going after a problem that doesn't exist since nobody is even teaching critical race theory.

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

But they want to put people on notice that any discussion of race or slavery might get you into hot water.

JON:

Are we headed for a place where teachers in seventeen states are afraid to discuss slavery in their classrooms?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

I've been throughout Florida; [we’ve seen] cases of teachers and librarians in a library where all the books have been taken off the shelf. I don’t want to say that's universal in all seventeen states, but it's absolutely happening,

JON:

Who is organizing to go to the school board meetings, and argue that this is outrageous?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

There are parents and teachers and legislators. Librarians have been activated. We have had members organize on these issues. Americans don't like book bans. Overwhelmingly, on a bipartisan basis, Americans reject them. So it's been really important to call this for what it is. They would like you to believe it's not a book ban — “we're just putting it behind the shelf” or “the librarian is reviewing it.” Simply naming it and calling gag orders gag orders [matters]. We call the whole thing an "ED Scare," because it's a series of tactics cutting across educational institutions.

JON:

When I was a kid, if a book was banned, I wanted to read it. Is there evidence that banned books are being read by kids outside of school? Could we have another Scopes Trial where teachers say, “You don't want me to talk about slavery — so sue me”?

SUZANNE NOSSEL:

Lawsuits are afoot, and there are some great teachers and administrators at the forefront of that. As to whether this just attracts more attention to books, that happens in a high-profile case like Maus. When it became public knowledge that Maus had been taken off curriculum [in Tennessee], there was a surge of interest and in sales. But you don't always have these lightning-rod cases getting that kind of attention. Some of the books are not that well known. Teachers and those who are ordering books for the classroom or for the library don't want to lose their jobs. They don't want to get hauled in front of some board, so they kind of quietly go along with it. So the kid may not even ever hear about the book or know to ask for it.

JON:

Thanks, Suzanne.

America in 2023 bears no resemblance to the vision I held in my youth. I recall a deep warm feeling of reassurance that free speech was inviolable because of PEN, ACLU, and hundreds of other groups of dedicated legal eagles who would forever defend my urges to speak my mind on any topic at any time, and also protect my crazy urges to read anything I damn well pleased. In my naive mind, I still expect faculty to freely speak scholarly opinions without student backlash. I also expect that the wide majority of my fellow citizens should have the common sense to allow and enjoy free speech in all its magnificent glory. Why, oh why, is book banning (and burning!) contemplated anywhere from California to the Gulf Stream waters to the New York Island?

THIS is why voting is existential!

Greatly appreciate this clear-headed, tough-minded discussion of an issue that can seem straightforwardly simple in principle, but that can get messy and complex and divisive in practice - and strongly second proposals to include in high school history courses the 20th century story of 1st Amendment free-expression battles, from the imprisonment of Eugene Debs for speaking out against US involvement in WW1 to the HUAC & McCarthy hearings of the 1950s to the two landmark press freedom Supreme Court rulings of the 1960s, in Times v. Sullivan and the Pentagon Papers case. And yes, very importantly, as mentioned, the now seemingly forgotten Skokie neo-Nazi court case, with ACLU chief Aryeh Neier, himself from a family of German Jewish holocaust survivors and victims, defending the right of goose-stepping American fascists to march through an Illinois town filled with holocaust refugees, despite the misgivings of many of Neier's colleagues and mass cancellations of ACLU memberships in protest. (Those 'American Nazis' never marched through Skokie after winning the right to do so.) Another ACLU case worthy of study is Eleanor Holmes Norton's defense of George Wallace's constitutional right to hold a campaign rally in New York City, in Shea Stadium. Both those examples have obvious legal and philosophical lessons for today's disputes over book-banning and academic freedom and free expression rights in schools and everywhere else. Thanks.