Are We Finally Curtailing Cancel Culture?

Hockey legend Bobby Hull, one of my childhood heroes, turned out to be a racist and anti-Semitic wife-beater. Here's why I'm for keeping his statue.

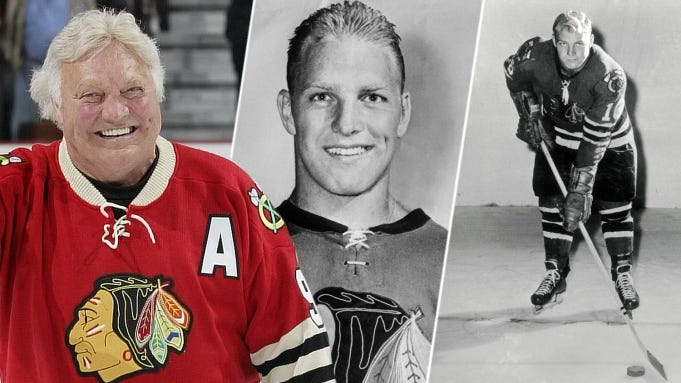

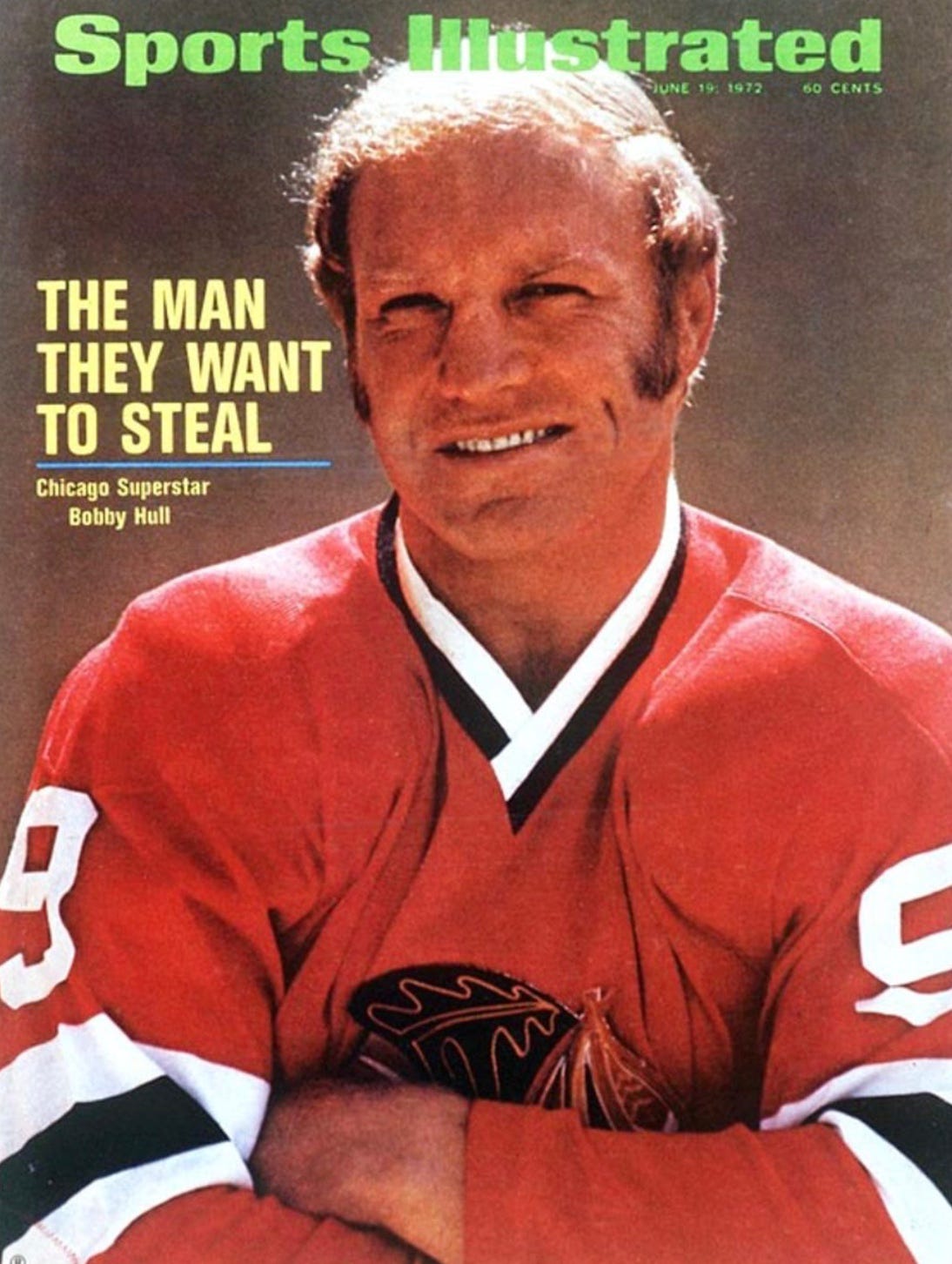

In the 1960s and early 1970s, I was a pint-sized hockey fan. More specifically, I loved the Chicago Blackhawks and especially their star, Bobby Hull, “The Golden Jet,” whose death last week left me pondering some big questions beyond sports: How should we — and history — view great achievers with great flaws? How far should cancel culture go?

Before we get to Robert E. Lee and Van Morrison, a little about my early years besotted with Chicago sports teams. After Hull died, I realized that when childhood heroes disappoint us, it hurts more — and complicates the reckoning.

Hull had a special place in my imagination in part because he was more distant than my other icons. I didn’t get to see him in the flesh nearly as often as I saw Ernie Banks and the Chicago Cubs. That was because Wrigley Field in those days was the only ballpark in the major leagues without lights, a godsend for me. I grew up a few blocks away and starting at age eight could go to dozens of baseball games a season with my friends and no adults. Admission to the bleachers, where we learned the facts of life from the Bleacher Bums, cost $1. One day when I was nine I interfered in play and won a game for the Cubs. True story. You can read about it in The Chicago Tribune.

None of that was possible with the Blackhawks, who played at night in Chicago Stadium, which was located in a rough neighborhood on the West Side. (I later wrote about that ancient arena, where FDR was nominated three times for president). My dad took me to a game or two and I went a couple times and sat up close with my friend Phil Marienthal and his father, George, who owned the legendary nightclub Mister Kelly’s, now the subject of a fine documentary.

Those Blackhawks games were unforgettable experiences, especially watching Hull streak down the ice in what the New York Times last week called one of his “locomotive sorties.” Hull — the NHL’s first true superstar — was hockey’s fastest skater (28.3 m.p.h.) and fastest shooter (118 m.p.h.). His slap shot was so hard that it led NHL goaltenders to wear face masks for the first time. The one holdout was the Blackhawks battered goalie, Glenn Hall, even though he confessed that he thought Hull’s shot would kill him in practice. After Blackhawk teammate Stan Mikita invented the curved stick, the shots he and Hull unleashed rose and dipped so perilously that in 1969 the league had to regulate the degree of curvature.

I only met Hull once and it led to what I consider the biggest humiliation of my childhood. In the mid-sixties, my father took me to the Ski Exposition at the old Chicago McCormick Place, not long before it burned to the ground in a famous fire. The exposition included other winter sports and a few local celebrities. I joined a group of kids mobbing Hull for autographs. I stuck a program in his face as he was trying to sign for someone else and he rudely pushed it out of the way and told me to wait my turn. When we got to the car afterwards, I wailed, “Bobby Hull yelled at me!”

I had no way of knowing as an eight-year-old that my flaxen-haired hero was not a good guy. Both the Tribune and The Times last week used “complicated legacy” in the headlines of their stories and that’s putting it mildly. Hull was proof that Canada can also produce brutish bigots, though his brother, Dennis (who also played for the Blackhawks), and son, Brett (a Hall of Famer with the St. Louis Blues), turned out well. After Bobby shocked the sports world by leaving the Blackhawks in 1972 for a ten-year $2.75 million dollar contract with the Winnipeg Jets (insane money then), his personal life turned ugly. His second wife accused him of beating her on multiple occasions; once, she feared he would push her over a balcony in Hawaii. His third wife called the police after he beat her bloody and when a police officer arrived, Hull was charged with assaulting him, too. (All charges were later dropped). The hockey legend was quoted saying that the Black population in the United States was growing too fast and that “Hitler had some good ideas. He just went a little bit too far.” After Hull denied making the comments, his daughter, Michelle, told ESPN, “The first thing I thought was, ‘That’s exactly like him.’”

I didn’t know any of this until last week’s obituaries. I left Chicago not long after Hull departed and haven’t followed hockey much as an adult. The news of his abusive behavior made me wonder how Hull will be honored at this week’s NHL All-Star Game and the Blackhawks’ first home game since his death. My guess is that league and team officials aren’t likely to take note of Hull’s dark side. After all, hockey is a mostly white, male, hidebound game that didn’t seem to get the #MeToo memo.

The larger question is how the rest of us should see flawed, even reprehensible, people who achieved greatness in their fields.

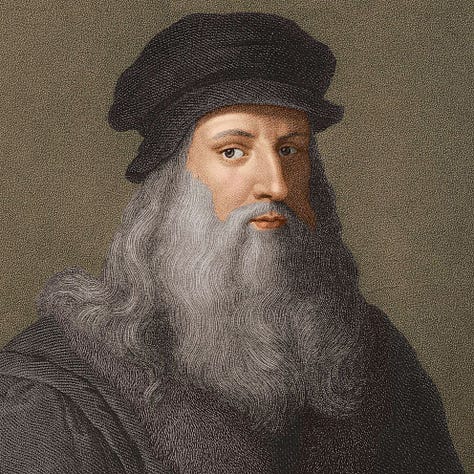

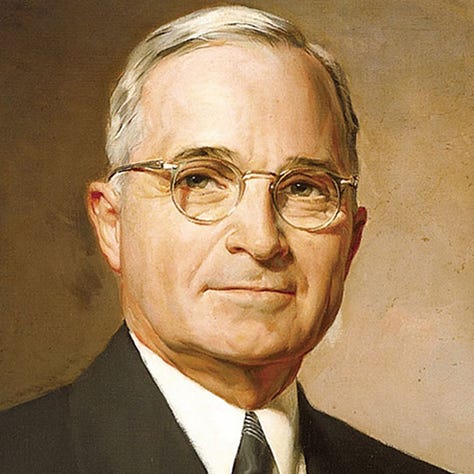

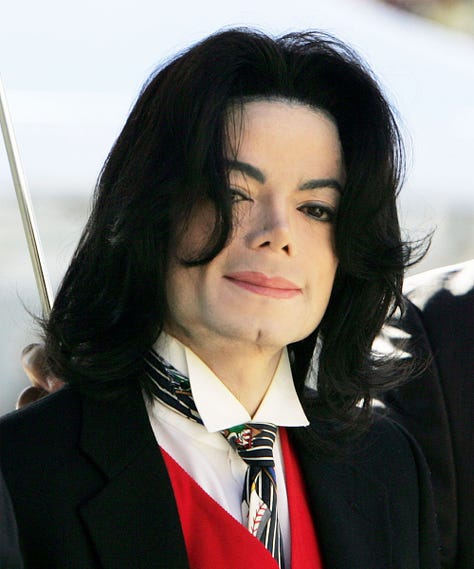

History is a long march on clay feet. Socrates and Plato were almost certainly pedophiles, as was Leonardo da Vinci, who according to Walter Isaacson’s biography had sex with a young boy in his household. Charles Lindbergh — the biggest celebrity of the first half of the 20th Century — accepted a medal from Herman Goering, and Ezra Pound and Philip Johnson were conspicuously pro-fascist. Harry Truman used the N-word and anti-Asian slurs. Michael Jackson spent way too much time cuddling little boys, and Van Morrison endangers people with his anti-Vaxxer nonsense.

History is a long march on clay feet.

It’s now seven or eight years since “cancel culture” materialized and we’re getting a little better at preventing it from overwhelming common sense. We know we shouldn’t ban Plato’s Republic, or stop admiring the Mona Lisa, or pull “The Spirit of St. Louis” down from the rafters of the Air and Space Museum. Pound’s poetry and Johnson’s architectural designs must be judged on their own merits, and Truman’s desegregation of the armed forces 75 years ago is more significant than his racist epithets. Thriller should remain in the canon of popular culture, and there’s nothing wrong with listening to Brown-Eyed Girl.

More of us are learning to draw essential distinctions. We’ve found consensus that Robert E. Lee was a traitor, so statues of him are being taken down. It made sense for Yale to stop honoring John C. Calhoun, the architect of secession. At the same time, all but a fringe element on the left recognize that founders George Washington and Thomas Jefferson —while also slaveholders — should continue to be respected and contextualized.

Meanwhile, we’ve begun to re-think the idea of the career death penalty. Most people I know aren’t mindlessly conflating Harvey Weinstein with anyone else accused of sexual improprieties. Al Franken’s forced resignation from the Senate was regretted by many of the same colleagues who had endorsed it 18 months earlier. Reasonable people can differ on whether it’s OK for Louis C.K. to play Madison Square Garden. There’s a bit of a backlash against weak college administrators. Last month, nearly 19,000 professors and students of art history and Islam signed a petition protesting Hameline University’s shameful dismissal of a professor who showed her class a famous painting wrongly attacked by some Muslims as “Islamophobic.”

When Marjorie Taylor Greene spreads conspiracy theories about Jewish space lasers causing wildfires then tries to marginalize Ilhan Omar for supposed anti-Semitism, you know cancelling people is just a new variation of smash-mouth politics.

Some things have changed for good. If Bobby Hull was a star today, he would be forced to apologize for his behavior, as Kyrie Irving of the Brooklyn Nets finally did last year for promoting an anti-Semitic documentary. And Hull’s statue might not have been erected outside the United Center, where the Blackhawks now play.

But there doesn’t seem to be any campaign in Chicago to take the statue down, and I’m OK with that. After all, Hull’s artistic creation was hockey, not himself. Which is why it’s easier to stop seeing Woody Allen films (especially those starring Woody Allen) than to go cold turkey on Eric Clapton for his noxious anti-Vaxxer views. You don’t cancel a guitar.

That’s about where we are today in processing these things. Let’s land heroes like the Golden Jet on a well-proportioned runway. Let’s hold him and others who violated new, overdue standards of decency to account. But let’s also remember their achievements — and how much some of us adored them.

Winners write history books and erect statues. Like all societies past and present, American society is often flawed or contradictory. Isn't it likely that Sitting Bull or Red Cloud would be offended by many of the images in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol and in the parks and village greens across America? Culture cannot be canceled - instead it must be negotiated.

It gets difficult when we try to draw lines between those who produce art (e.g., Caravaggio), those who star in their art (e.g., Woody Allen), those who existed in a time when something we consider wrong or taboo was accepted (e.g., Plato) and those whose “art” was their game (e.g., Bobby Hull). We waste too much time drawing the lines, in my opinion. I’ll never have a set of formal or informal rules that determines whether I will personally “cancel” someone. I take it case by case. Certainly, someone who I do decide to “cancel” personally might be a source of inspiration for my neighbor, and it’s not my place to tell them who they, in turn, should cancel. Personally, I must confess that, when something is cancelled or banned, I’m immediately determined to check it out. That said, there is a difference between enjoying Bobby Hull’s art as a player and lionizing him as a person. I think that what we need to avoid is, on the one hand, ignoring the dark side of people through blind hero worship and, on the other, automatically consigning people – or their creations - to the rubbish heap because of their flaws.

I’m glad you’re writing about this.